My Journey Through the Silent Night, Deadly Night Series Concludes With a Look at the Underwhelming 2012 Reboot Silent Night

I expected more from the director of Werewolves!

Two weeks ago I’d never seen a Silent Night, Deadly Night series. Now I feel so personally invested and strangely protective of the franchise that I am vaguely insulted on its behalf by the 2012 sorta remake kinda reboot Silent Night.

It was the first theatrically released entry since 1987’s Silent Night, Deadly Night Part 2, and it was better received critically than other entries in that critics weren’t personally offended by its existence and didn’t seem to despise it with a white-hot, burning passion.

To me, however, Silent Night is not only not a satisfying Silent Night, Deadly Night remake; it’s not a Silent Night, Deadly Night remake at all. Sure, there are a few nods to fans of the original series, like a winking reference to the legendary “garbage day!” scene and someone being impaled on antlers, but really, all Silent Night takes from the notorious 1984 controversy magnet is the idea of a lunatic in a Santa suit going on a Yuletide killing spree.

Silent Night faithfully recreates at least one scene from Silent Night, Deadly Night but the changes help illustrate why the film is infinitely less interesting and successful than the provocation that inspired it.

In it, a young person goes to a mental hospital to visit their ostensibly catatonic and mute grandfather, only to have Gramps suddenly come alive when they’re alone and start talking about the evil side of Christmas and how Christmas Eve is the most terrifying night of the year.

When the family returns, the grandfather once again feigns catatonia. This scene is tremendously effective in Silent Night, Deadly Night because the young person in question is Billy Chapman, the deeply traumatized slasher from the first film.

The scene works because the child actor seems legitimately and understandably terrified. This is due to the grandad’s warning and sinister behavior, but it is also because he has been left alone with a weird old relative he barely knows, which is terrifying under the best of circumstances.

This show-stopping early set-piece is also shatteringly effective because Silent Night, Deadly Night makes us care about Billy before he becomes a monster. We see the world through his innocent eyes. It is a place of infinite horror and destruction, where your mother is sexually assaulted before your eyes mere moments before her throat is slit.

In Silent Night, the young person getting freaked out by Grandpa’s odd outburst is a cartoonish stoner who is in the movie for about fifteen minutes. We don’t know or care about this character. He’s not the protagonist. He’s not the villain. He’s just some guy.

Having this happen to a random supporting character lessens the impact, as does making him a dude in his teens or early twenties instead of a vulnerable child who is about to see things no one should ever see, particularly as a mere kid.

Instead of the unforgettable Billy Chapman or his even more memorable kid brother Ricky, “Garbage Day!” Caldwell, the protagonist here, is heroic cop Deputy Aubrey Bradimore (Jaime King), a widowed small-town cop with a lot of baggage.

She's still reeling from the recent death of her husband and is worried that she won’t measure up to the high standard set by her sheriff father, Hank (John B. Lowe).

Aubrey's insecurities are further fueled by the virulent sexism and condescension of boss Sheriff James Cooper (Malcolm McDowell). Misogyny is an insidious cultural plague that takes many different forms, but it’s seldom as cartoonish as it is here.

McDowell’s chauvinistic Sheriff stops just short of saying that he doesn’t respect Aubrey because she’s a girl, and girls spread cooties and belong in the kitchen, making hubby a sandwich, not in the workforce investigating murders.

The sexism that Aubrey faces may be a throwback to the toxic work environment of Kim Levitt, the driven working girl Neith Hunter played in Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: The Initiation. But judging by the faithlessness of this quasi-remake, I doubt the filmmaker’s knowledge of the franchise is that granular.

Screenwriter Jayson Rothwell reportedly hadn’t seen Silent Night, Deadly Night when he wrote the script for Silent Night. He based the screenplay instead on the Covina massacre. In this real-life bloodbath, a disgruntled, recently fired electrical engineer named Bruce Jeffrey Pardo entered his ex-wife’s family holiday party dressed as Santa Claus and proceeded to kill nine people with handguns and a homemade flamethrower.

It was a scene of almost unimaginable horror and devastation that Silent Night cynically exploits for cheap shock. That purposefulness, tastelessness, and vulgarity might be the elements of the film most analogous to the five films that preceded it.

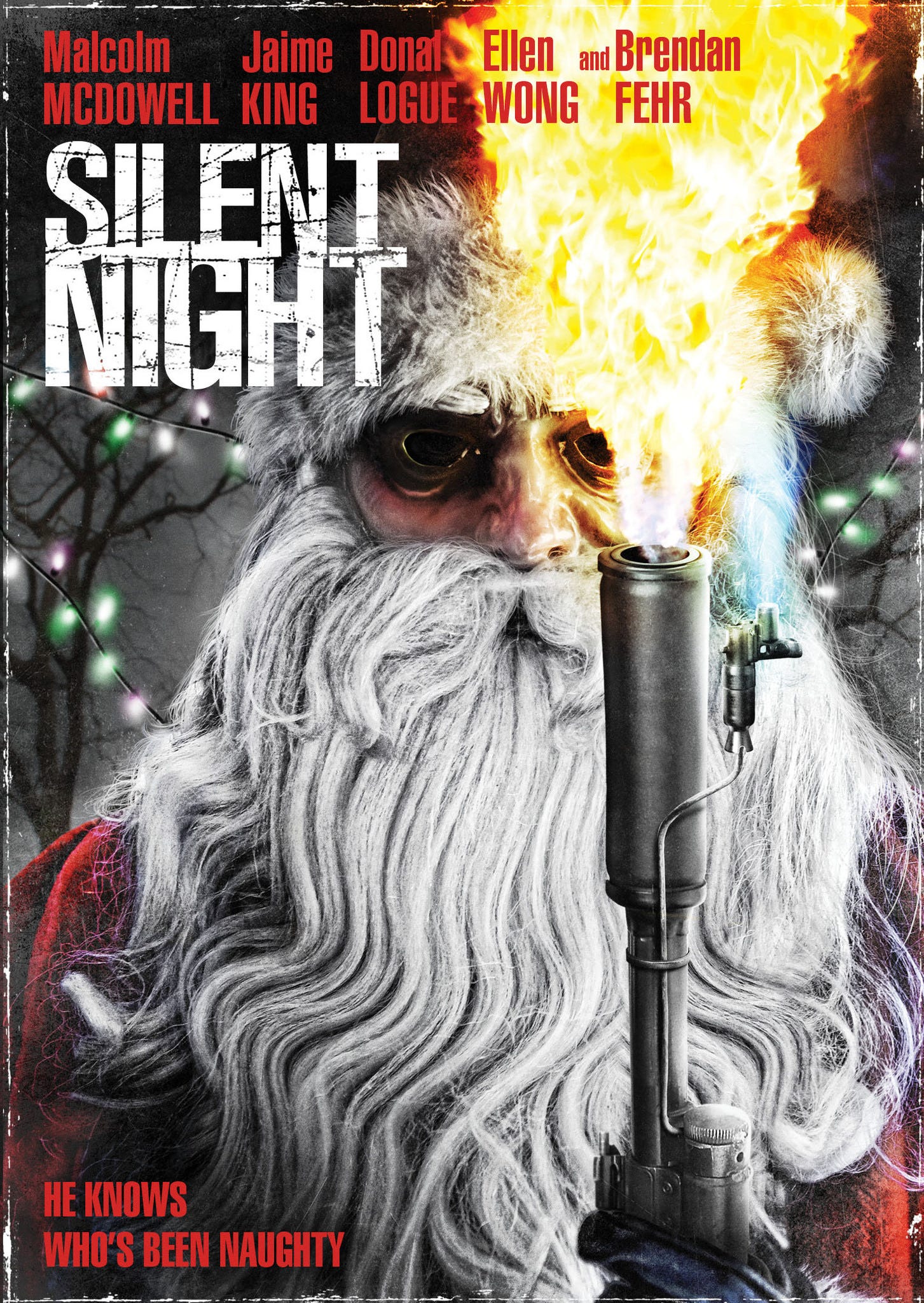

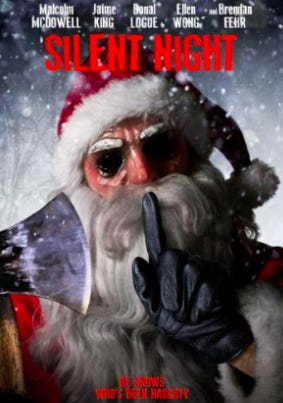

A madman in a Santa Claus suit and a creepy face mask is slaughtering the residents of small town Cryer, Wisconsin, on Christmas Eve before its annual Santa Claus parade. But who could the mystery murder-happy maniac be?

Could it be a foul-mouthed, cynical, and nihilistic store Santa played by Donal Logue? Or could the guilty party be Reverend Madeley (Curtis Moore), a hypocritical man of God more interested in shamelessly ogling his flock rather than helping them through their spiritual crises? Alternately, could the sinister Santa be a drug dealer, degenerate, and all-around bad dude Stein Karlsson (Mike O’Brien)?

In horror movie tradition, the mass murderer masquerading as jolly old Saint Nick has scary slasher super-strength. Powered by a hatred of humanity and a need for revenge, he’s as powerful as a superstar wrestler or professional strongman.

Silent Night follows its heroine as the mystery killer wracks up an impressive body count of people he considers naughty and consequently worthy of punishment.

This element barely registers since the bad guy is fundamentally silent (not unlike the characters in the John Woo movie of the same name), so we’re never privy to his inner life or private thoughts.

He’s not the tragic figure Billy was in the first film or the figure of unintentional hilarity his enthusiastic younger brother was in the cult classic sequel Silent Night, Deadly Night Part 2. He’s just another holiday-themed slasher going about his grisly business with a regrettable dearth of personality.

What made Billy unforgettable wasn’t the way he killed or the number of people he killed. No, what defined him was a deep inner sadness rooted in formative trauma. That’s lost here. It turns out that the killer is, in fact, someone with a grudge, but we learn almost nothing about them beyond their formative trauma.

By 2012, there was nothing particularly novel or shocking about the idea of a maniac in a Santa suit slaying bad little girls and boys. By that point, Santa-based Christmas horror movies were a thriving sub-genre.

Silent Night, Deadly Night shocked and offended a subsection of the American public that, to be fair, actively seeks out things to be shocked and offended by. It was vulgar, crude, and shameless, but it was also unique and, in its own way, special.

Silent Night is vulgar, crude, and shameless but nothing special. It’s just another Christmas slasher movie devoid of the warped personality that defines even the weakest entries in the Silent Night, Deadly Night series.

::This element barely registers since the bad guy is fundamentally silent (not unlike the characters in the John Woo movie of the same name)::

Huh? What John Woo movie? I'm...baffled by this comment, Nabin.

Sounds like this wasn't so much a "remake" as "Hey, I have this IP we can exploit!"