My Dad is Dying and I Am Sad

I don't generally post personal essays here unless it's important, and it doesn't get more substantive or sadder than losing a parent for the first time

For the past few years, my older sister warned me to expect the worst when I visited my now seventy-seven-year-old dad in the nursing homes where he has lived for the past decade or so.

Because I had low expectations, I was always pleasantly surprised by my father’s condition. He’s had Multiple Sclerosis for over half a century. He had not taken good care of himself, yet he was lucid, conversational, and happy to see and talk to me.

That, unfortunately, was not true of my last visit. I’d visited him about a month earlier, and was once again relieved that, while he struggled with UTIs and was in and out of the hospital regularly, I was still able to talk to him the way that I always had.

I dreaded the worst when I visited my dad last week. For the first time, I was not pleasantly surprised by how he was doing. He was doing as badly as my sister had said, if not worse.

For the first time in my life, my dad did not seem to recognize me. He didn’t seem to understand that I was his son and had come to visit him from Georgia. For three days, I went to the hospital and watched my dad fade in and out of consciousness without saying a word to me.

It broke my heart. My father had not been doing well for a long time, but this was the first time I felt like I was visiting him on his deathbed. I dreaded the end. Now it appeared that it was imminent.

My father had always loved to eat. He derived unseemly joy from getting free bread before meals at restaurants. That was the kind of thing that made him deliriously happy.

He loved to laugh. He loved life. The gaunt man in front of me had to be forced to eat. He could smile weakly, but the laugh that had sustained me through my childhood was gone.

For the first time, I did not know what to say to my dad. We’d always had a powerful, easy, profound connection, but I didn’t know how to reach him in his diminished state.

Thankfully, on the second-to-last day of my visit, when I was joined in my dad’s room by my older sister, her husband, their daughter, my younger sister, her insanely adorable baby daughter, her husband, and my dad’s brother, my old man became lucid. We talked and watched Jeopardy, and I fed my father and gave him water to drink.

It was wonderful and heartbreaking at the same time. I was grateful to be able to communicate with my dad, but it was hard to ignore the sense of finality that hung over our afternoon. I was happy to have a good day with my dad. I worried that it might be the last.

We recently made the difficult decision to put my dad in hospice care. He will no longer be going to the hospital. The focus is on pain management, on making the time he has left as peaceful and happy as possible.

I haven’t been able to think about anything other than my dad since I got back from Chicago. I’ve found distraction going to the movie theaters as often as possible, but every free thought is dominated by grief over my father’s condition.

I’m working on the seventeenth and hopefully final draft of The Fractured Mirror. I can generally burn through a draft in four or five days, which is no small feat, considering it’s 524 pages long. I still love the book, but as I work on it now, I feel like I’m underwater and in slow motion.

For the last three years, The Fractured Mirror has been the biggest, most important aspect of my professional life, my magnum opus. Now everything seems so inconsequential in light of my father having weeks or months left to live.

Work has always been my distraction, but some things are so heavy and intense that it’s impossible to distract yourself. That’s what I’m dealing with now. I try to be productive, but I don’t have the energy or the focus to do more than the minimum. My mind is elsewhere and my heart is broken.

That’s part of the reason that I’m writing this. I want to process what’s happening to my dad in a manner other than staring grimly into the distance and feeling simultaneously numb, depleted, and overwhelmed with emotions and memories.

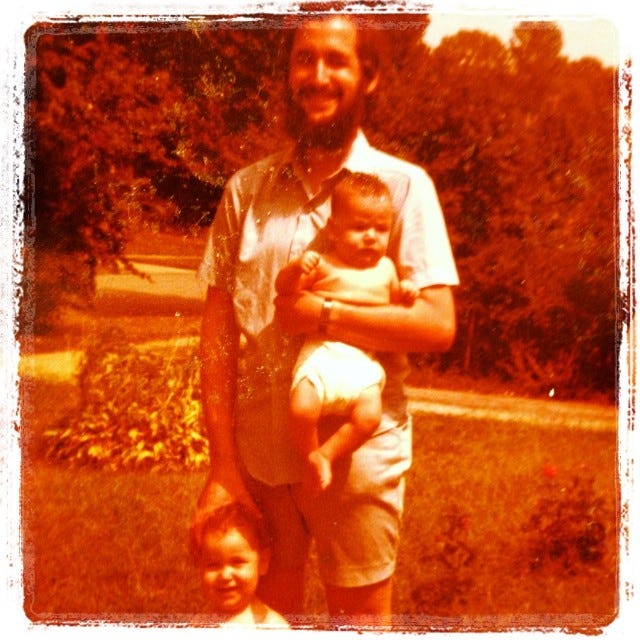

So much of who I am and what I love comes from my dad: my sense of humor, my love of history, my terrible dad jokes, my politics, my love of movies, music, and pop culture. I fell in love with film as a child because my dad would take me to the multiplex when he worked as a real estate agent with an office in a mall. I’ll never forget the delight on my dad’s face when he brought home a miraculous contraption called a VCR that would allow us to see anything we wanted in the privacy of our own home. Because my dad is a big weirdo, he made sure his son saw plenty of classic musicals. He introduced me to Hip Hop by renting me the Run-DMC video collection.

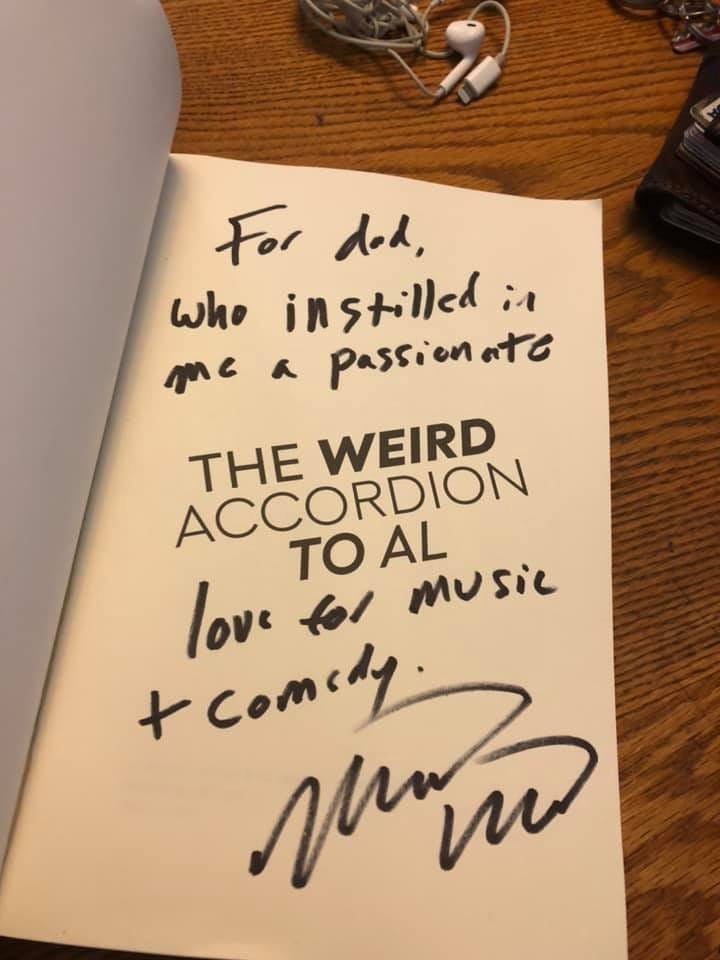

My dad took me to my first “Weird Al” Yankovic concert. He bought me Leonard Maltin and Roger Ebert’s movie guides to fuel my nascent cinephilia. He introduced me to The Twilight Zone, which began a lifelong love of horror and science-fiction anthologies.

My dad was always extraordinarily proud of me and my professional accomplishments. I felt like he lived through me and my literary success.

When I published my memoir, The Big Rewind, in 2009, I was able to share my dad with the world. The Big Rewind is, in many ways, a book about my dad, his innate joyfulness in the face of incredible obstacles, and his preternatural resilience. That’s why I dedicated it to him and my older sister.

For much of his adult life, my father lacked what is supposed to bring happiness: money, resources, a house, a car, and a career. Yet, he had a unique gift for joy nonetheless.

It took very little to make my dad happy. I developed my sense of humor because, as a child, I could make my dad laugh. That meant everything to me.

About a decade ago, I moved from Chicago to suburban Atlanta after losing my job at The Dissolve, so that my wife’s parents could help us with our baby boy, and I could leave a city I once loved with my heart and soul but had become filled with traumatic memories and broken bonds.

It was the right thing to do, but I have enormous guilt over choosing my own needs and the needs of my wife and child over those of my dad. I can’t help but feel like I abandoned him when he needed me most, and I was never as good about writing, calling, and sending pictures as I should have been.

Growing up with a dad with Multiple Sclerosis had an indelible impact on me. I had no idea that I was also disabled, and that I would pass those disabilities onto my sons. I was lucky and unlucky to have an invisible disability in AuDHD.

As a child, I remember seeing my dad struggle to support himself and two complicated children on a fourteen-thousand-dollar government pension. I hated to see my dad like that, just as it fills me with shame that my ten-year-old sees me struggling the way my dad did.

My mother abandoned me when I was a baby, so my dad has been the only parent I ever had, although, to be fair, I guess my dad, my older sister, the Chicago group home system, and pop culture technically raised me. That made me protective of him. He did many wonderful things for me growing up, like keeping me from having to live with my crazy-ass mother.

When my mother died at sixty-nine some years back, I felt nothing but an emptiness commensurate with her absence. When my father passes, I am going to feel everything.

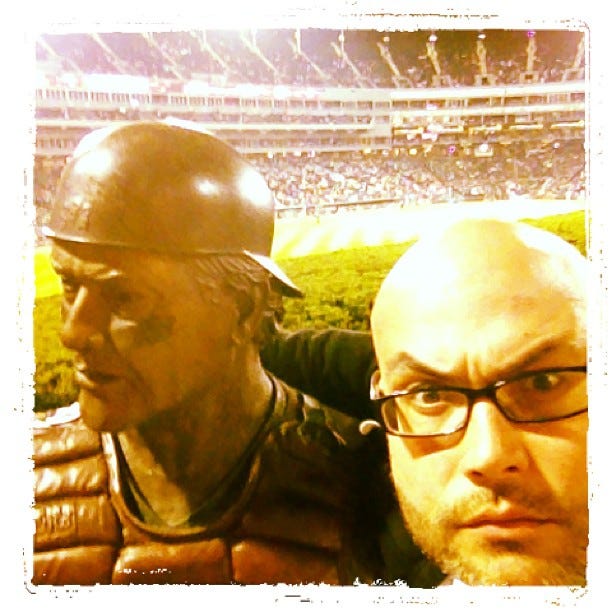

My father has expressed a desire to have his ashes sprinkled on what I will always call Comiskey Park. That choked me up because baseball was one of the many things we shared. When the world was scary, overwhelming, and unfathomably confusing, you could always talk about how the White Sox were doing.

You technically aren’t allowed to scatter ashes on a professional baseball field, but I want to make my father’s wishes a reality.

I’m not entirely sure how I’ll do so, but the odd request is my dad in microcosm: peculiar, Chicago to the core, strange, darkly funny in a manner both intentional and unintentional, and utterly original.

My dad and I will make one last trip to the ballpark together. I’ll be bawling like a baby, but even in death, my father will still find a way to make me laugh and express his eccentricity and extraordinary strength of character.

So sorry to hear about your father, Nathan. My father passed away in 2011 and I'm still processing things (and haven't really taken necessary steps to do so, but that's in keeping with family tradition ... tamp it all down!). My dad loved science fiction, and sometimes would wake me up late at night to watch an old Flash Gordon movie or some such thing, and took me and my friends to see Star Wars the week it came out in 1977, so I guess he got me started on my pop culture-obsessed path as well. From the sound of your loving words, your dad did dadding right, in the best way he was able, and that's one of the best things a boy can hope for in this life. My deepest condolences.

I'm always at a loss for words in situations like this, so let me just say that I'm so sorry.

Because I always have to temper these things with some humor, let me just say that when my dad passed away in 2009, and I picked up his ashes from Maryland to bring them to New Jersey to be sprinkled in the ocean, I made a lot of jokes about going into a restaurant with the ashes and asking for a table for two. I know my dad would have thought it was funny, we shared the same morbid sense of humor.

Please take care. <3