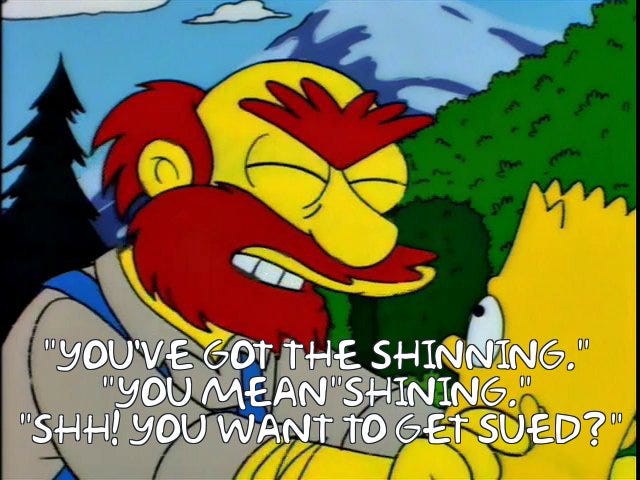

It would be easy to dismiss Stephen King, based on his first three feature film adaptations, as a prolific author of novels about people with psychic abilities. That’s the theme of 1976’s Carrie, 1980’s The Shining, and 1983’s The Dead Zone.

It’s a theme that did well for King. Carrie, The Shining, and The Dead Zone aren’t just three of the most iconic movies in King’s sprawling filmography; they’re three of the most iconic horror films ever made. I would go even further and say that they’re three of the most iconic motion pictures in American history.

Like Steven Spielberg, one of the only figures in American pop culture who can match King in popularity and influence, the prolific author trafficks in the mundane and the fantastic, the poignantly banal and the phantasmagoric.

Like Carrie’s Carrie White and The Dead Zone’s Johnny Smith, Danny Torrance (Danny Loyd) of The Shining has a psychic ability that sets him apart from the rest of humanity.

The Shining is about a boy with psychic powers. To Stephen King, it was more pointedly, purposefully, and importantly about a man in the grips of alcoholism. That had tremendous meaning to King since he was an alcoholic and drug addict still over a half-decade away from getting clean and sober when The Shining was released.

King saw The Shining as the story of an ordinary man who goes mad. He consequently wanted someone like Jon Voight in the lead, which is ironic considering that Voight is now best known for having insane political beliefs and a reverence for Donald Trump that can only be a product of profound mental illness.

That’s why King hated the casting of Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance. He thought casting the star of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest broadcast the character’s descent into mental illness.

King complained to Deadline, “The character of Jack Torrance has no arc in that movie. Absolutely no arc at all. When we first see Jack Nicholson, he’s in the office of Mr. Ullman, the manager of the hotel, and you know, then, he’s crazy as a shit house rat. All he does is get crazier. In the book, he’s a guy who’s struggling with his sanity and finally loses it. To me, that’s a tragedy. In the movie, there’s no tragedy because there’s no real change.”

King is wrong about The Shining being boring and underwhelming, “a big, beautiful Cadillac with no engine inside it,” to borrow his description. “Boring” is a criticism that is vague to the point of meaninglessness.

The author is not wrong, however, in his conviction that in Kubrick’s film, Jack Torrance is a lunatic who gets crazier and crazier until he’s chasing after his wife and son with an axe in a murderous frenzy. I would go further and argue that Jack is crazier than a shithouse rat, not merely as crazy. He’s nuttier than a squirrel’s diet.

Jack begins the film at his sanest and most professional, which is not remarkably sane or professional. King sees The Shining as the story of someone trying to hold onto their sanity, but even at the beginning, Jack is canonically a violent alcoholic whose inability to control his drinking or his temper has negatively affected his personal and professional life.

Even before his fragile soul is taken over by the malevolent animistic forces of The Overlook Hotel, Jack’s wife, Wendy (Shelly Duvall), and son are scared of him.

Isolation is the last thing Jack needs, yet he misguidedly seeks it when he applies for a job as the lonely caretaker of a spooky old hotel full of bad vibes.

Jack moves his family into a murder house. That rarely goes well. Meeting his new bosses, Jack sports a plastic smile of cynical calculation. He’s not grinning organically but rather because that’s what new employees should do. They’re supposed to smile and be confident, positive, and optimistic about their new job, no matter how grim or joyless.

The fake smile is performative rather than sincere. Though he is played by a brilliant actor who shares his first name, Jack Torrance is acting badly. He’s doing a piss-poor imitation of a responsible husband, father and employee.

Jack Torrance is trying to fool himself as well as his new employers. He wants to believe that he can be the man that he is pretending to be and emerge from five months of total isolation with nothing but his wife, child, and demons to keep him company, happy, refreshed, and ready to face the world, preferably with a freshly written manuscript in hand.

Jack is saying things that he delusionally hopes are true. When Jack learns that a previous caretaker cracked under the inhuman pressure of being alone for long, agonizing months at a time and brutally murdered his wife and daughters, he responds disingenuously.

Rather than acknowledge the horror of what he’s been told, Jack gingerly treats the crime like juicy trivia that his horror-obsessed wife will find fascinating, not a terrifying portent of what’s to come.

Kubrick shoots Jack’s car driving to The Overlook from a helicopter in a dramatic shot that makes the automobile look as tiny and inconsequential as an insect. These shots underline the family’s loneliness and isolation.

We see the Torrances' car from the vantage point of a silent and unhelpful deity. Wendy and Danny are on their own. They must save themselves; neither God nor Stanley Kubrick will help them.

Jack stopped drinking after hurting his son in a drunken rage, but he has not addressed the issues behind his drinking and his violence. Jack is what is known in Alcoholics Anonymous as a Dry-drunk. Because Jack has not done the work or the self-reflection, his sobriety is fragile. His mind is still fixated on alcohol and drinking. He’s looking for an excuse to cast dreary sobriety aside and give in to his sickness.

Jack barely tolerates his wife under the best of circumstances. She’s all too familiar with her husband’s rages. She knows just how little it takes to set him off.

Wendy does what the partners of addicts generally do. She makes excuses. She minimizes his abuse. She tries to keep the darkness at bay for her child and herself. She lives in fear.

A free-floating sense of dread infects everything in The Shining. From the very beginning, something is irrevocably off.

The vastness of the Overlook makes the Torrance family seem tiny and inconsequential, particularly Danny. Children are, by definition, powerless. They have only as much power as adults give them or that they take for themselves.

Danny is particularly powerless and vulnerable. He lives in fear of his father. He’s psychically gifted, but his telekinetic powers are a curse as well as a gift since he sees things that he does not want to see and that no child should see.

Scatman Crothers plays the film’s fourth most important role, Dick Hallorann. On paper, he’s a quintessential Magical Negro. He’s a soothing, reassuring African-American cook with superhuman powers willing to risk his life for the sake of a white family he met briefly.

Kubrick offered the role to Slim Pickens, who accepted on the condition that he did not have to film 100 takes of any scene. Kubrick couldn’t make any promises, so Kubrick went instead with the voice of Hong Kong Phooey.

It’s a terrific, nuanced performance. In a movie and a world where everything is off, dark, and strangely ominous, Crothers alone is soothing. He’s the soft, sane, raspy voice of kindness and experience, the supportive, empathetic father figure Danny deserves but does not have.

Crothers has the unenviable task of delivering extensive exposition without making it feel like he’s spoon-feeding us the necessary information.

I love that Dick’s defining features are that he’s an empathetic, perceptive professional and an all-around terrific human being and also that he likes naked ladies so much that he has a black velvet painting of one above his bed.

He’s not entirely lacking in agency; he’s just all about helping white people and appreciating the beauty of the unclothed female form.

Jack Torrance begins the film on the brink of madness. When he tries to assure his bosses that he’s the right man for the job, he adopts a mask of sanity that slips further with each successive scene.

After a Bratz: The Movie-style one-month time jump, Jack has clearly lost what’s left of his mind. When he invites a traumatized and appropriately scared Danny onto his lap and asks him whether he’s enjoying the nightmare he has subjected him to, his ostensible happiness is creepier and more unnerving than it would be if he expressed abject misery.

Alcohol and cocaine helped King become a prolific and uniquely successful author early in his career, even as they played havoc with his health, sanity, happiness, marriage, and family life.

They were unholy tools that allowed him to stay up at all hours of the night, banging away at his typewriter as he cranked out the novels, novellas, and short stories that would make him arguably the most commercially successful American author.

Alcohol does not have the same effect on Jack. He clings to a fuzzy concept of professionalism as a lifesaver in a sea of ennui. Wendy seems to be doing most of the actual caretaking of the hotel, and the writing of Jack’s novel is stuck at the “repeating the same sinister phrase over and over again, to the point of insanity and beyond” phase.

Jack is violently estranged from their wife and child, who fear his bottomless capacity for violence. He finds escape in a ghostly realm of the hotel’s distant past, a Depression-era heyday with booze and naked female flesh, and a bartender who speaks in sinister riddles and has sinister demands for the once and future caretaker.

No film has used the spookiness of the past and WASP revelry better than The Shining. It’s The Great Gatsby reconceived as a ghost story about a man willing to kill his own family with an axe for his shot at the American dream.

Jack Torrance finds the direction he’s been seeking when he gets furtive but unmistakable orders from a ghost bartender to murder his family for bringing an outsider into the situation.

That outsider is Dick Halloran, who is rewarded for his selfless kindness and willingness to put the needs and safety of others above his own by getting axe-murdered immediately upon reaching The Overlook.

In that respect, Crothers’ kindly cook embodies another pop culture archetype: the African-American who is the first person to get killed in a horror movie.

The Shining made spectacular use of a then-new development in the Steadicam, a technological marvel that allows a film camera to move with unparalleled fluidity and speed.

Kubrick smartly uses a Steadicam in scenes that follow Danny’s Hot Wheels as he drives around the hotel and in the climactic chase through the maze, which is The Overlook’s defining characteristic.

The Shining is more than just a popular contender for the scariest movie of all time; it is arguably the single most iconic horror film ever. As the riveting documentary Room 237 chronicled, it has spawned numerous conspiracy theories about its true meaning.

The conflict between Stanley Kubrick and Stephen King, who hated what possibly the greatest filmmaker in American history did with his deeply personal novel, has become the stuff of pop culture legend.

In recent years, much of the conjecture surrounding the film has focused on Kubrick’s treatment of Duvall and its impact on her mind, sanity, and career.

A condescending, paternalistic, and insulting narrative emerged depicting Kubrick as a monster who took advantage of Duvall’s emotional fragility in a way that worked for the film but destroyed her psychologically.

This ignores Duvall’s success post-The Shining and posits her as a victim rather than a survivor.

This narrative gained traction because The Shining is so scary and so unnerving for both understandable reasons and ones that are difficult to explain that fans think that, on one level, it must be real, but with Kubrick as the maniac terrorizing Duvall the actress rather than Jack Torrance menacing his long-suffering wife.

The Shining ends in a way that is both anti-climactic and perfectly iconic.

First, we have that unintentionally comic image of a frozen Jack Torrance looking like an unfortunate cartoon character in the snow, a human popsicle, and then the famous last shot of a group picture from July 4th, 1927, with a grinning man who looks an awful lot like Jack in front.

It seems inadequate to think of The Shining as merely a scary movie, or even just a movie at all, since, at this point, The Shining transcends horror and cinema.

The Shining isn’t just a movie. It’s not even just a cult movie. It’s something closer to an actual cult, which helps explain why it’s more relevant than ever and never seems to get old.

I reviewed Wolf Man recently and was struck that it has the same dynamic as The Shining and a similar plot, but is nowhere near as effective or scary.

Still in my top ten to this day. Scared the crap out of me when I first saw it at 11 years old and it still does! The clinical detachment with how its shot and acted makes it seem like you're watching a cursed film from the very first frame. No wonder so many conspiracy theories have emerged from it? That the horror is happening in broad daylight, in perfectly framed clarity, also adds to the sense that there's no escape.

I love your description of The Shining being "...The Great Gatsby reconceived as a ghost story about a man willing to kill his own family with an axe for his shot at the American dream." How our sense of purpose and duty can be so easily manipulated by malevolent forces simply because people lack meaning and direction in their lives. A suicide mission is still a mission.