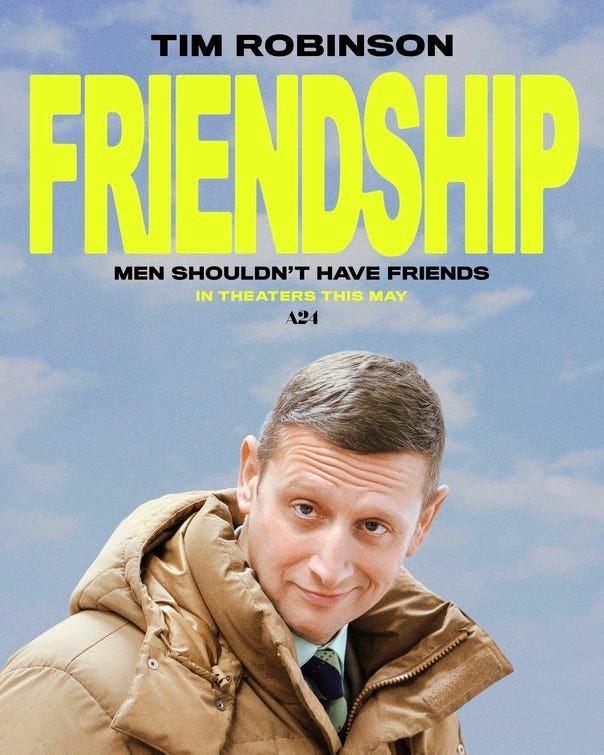

Tim Robinson Menaces Paul Rudd in the Painfully Relatable Dark Comedy Friendship, AKA You Make Me Deeply Uncomfortable and Maybe You Should Get Away From Me, Man.

If you like feeling uncomfortable, boy have I got a movie for you!

I decided to watch I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson a few years back with my wife, knowing she would probably dismiss it as “that weird anti-comedy you like so much.”

I do, in fact, like anti-comedy. I think Freddy Got Fingered is a masterpiece. Elaine May is one of my favorite writers.

My wife is less of a fan. She finds it less funny-weird or funny-strange than funny-unfunny. It did not take long for my wife to give I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson the gong. She told me to leave and to take Tim Robinson with me.

I was more intrigued and amused because I generally enjoy comedy of awkwardness.

I made a vague plan to watch I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson at some point in the years ahead, which, true to form, I never followed up on.

Before, I would blame it on flakiness, but I have ADHD AND autism AND bipolar 2, so I have a neurological excuse for never following up on things.

I didn’t have to watch I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson to be exposed to Robinson’s wildly divisive brand of cringe comedy.

Like a much less famous Nicolas Cage, Robinson is now more meme than man. I Think You Should Leave isn’t going to top Grey’s Anatomy in the ratings but Robinson has viral fame and cult stardom up the wazoo. Even if you don’t recognize Robinson’s bland, generic, forgettable name, you’re undoubtedly familiar with the meme of him dressed as a hot dog vowing, “We’re all trying to find the guy who did this.”

You’re probably familiar with all of the other memes as well. So many memes! Too many, maybe!

Robinson is a cult superstar. He’s virulently viral, a King of cringe comedy.

Like the simpatico Nathan Fielder, Robinson’s comedy of awkwardness feels unmistakably like the comedy of autism.

As far as I know, neither Fielder nor Robinson has been officially diagnosed with autism, but their comedy feels deeply neurodivergent.

That is true of Robinson’s portrayal of Craig Waterman, a Colorado husband and father who has managed to marry a beautiful woman and achieve considerable professional success despite a genius for misreading social situations, saying the wrong thing and making people so skin-crawlingly uncomfortable that they want to shrivel up into a little ball and disappear.

Craig shows many signs of neurodivergence. He tries and fails to fit in with the neurotypical, to figure out their curious customs and ways so that he can do a better job impersonating someone not on the spectrum.

It sucks to see a character in a movie or television show who is awkward, strange and offputting and barely tolerated by those around them and think, “I bet they’re autistic, just like me.”

I suppose that’s why I was able to empathize with Craig and find his painful fumblings all too relatable, even though he is a fundamentally unlikable character who perpetually expresses off-putting sentiments.

Craig’s introduction and that of his wife, Tami (Kate Mara), speak volumes about his personality, their dynamic, and her suffering.

Tami suffers twin tragedies. She gets cancer that has been in remission for a year when the movie opens. She’s talking earnestly and emotionally about her battle with cancer and her inability to orgasm.

Craig never knows what to say. He’s particularly flummoxed to have to communicate in the surreal context of a cancer survivors' support group, so he jokes that, unlike his wife, he has no problem orgasming.

Craig doesn’t just make us uncomfortable; he also makes the other characters uncomfortable.

Watching Friendship I had the problem that some have with Michael Scott and The Office. Craig is such an oblivious and off-putting doofus that it’s hard to understand how anyone can tolerate him for an extended period of time, let alone marry, employ, or befriend him.

Craig isn’t a husband or a partner: he’s an affliction nearly as bad as cancer. Cancer eventually ended, but her cursed union to an unbearable man-child drags on interminably. It’s hard to see what attracted Craig to her because he is conspicuously devoid of admirable qualities. Work-wise, at least, he seems to be an idiot-savant, but we only see the idiot part of that equation.

The poor woman has a friendship with a hunky fireman ex that’s seemingly much more. That might be the only thing keeping her from giving up hope completely. She hasn’t just caught some tough breaks; she’s suffering the trials of Job.

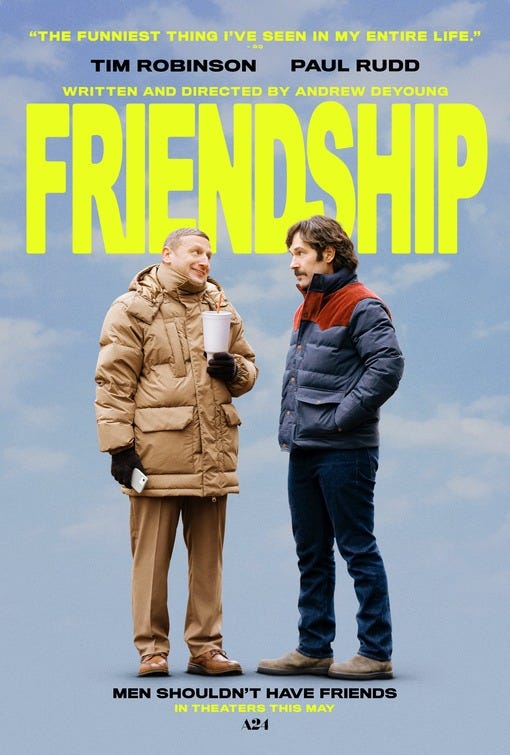

When a package for Austin Carmichael (Paul Rudd) is mistakenly delivered to his home, Craig drops it off and becomes instantly besotted with a neighbor who is everything he is not. For starters, being in his company is not a sadistic form of punishment, and people are attracted to him rather than repulsed by his presence.

Austin has what Craig considers an impossibly glamorous job: he is a weatherman on the local morning news.

If Robinson brings I Think You Should Leave energy to his role in the proceedings, Rudd delivers a performance that suggests both Anchorman’s Brian Fantana and I Love You, Man’s Peter Claven.

Friendship is a much darker take on the early film’s frenemy dynamic. Think of it as You Make Me Deeply Uncomfortable and Maybe You Should Get Away From Me, Man.

Austin is initially flattered by the way Craig reveres him and follows him around like a puppy. Austin shows him some of his special places, most notably an aqueduct and a forest where they gather mushrooms.

It’s a one-sided bromance. Austin may not be as cool as he thinks, but he has a lot going for him, including a wife, a glamorous job, and a circle of friends. Austin makes the mistake of introducing Craig to them.

The group hangout proves Craig’s undoing. He makes the mistake of going way too hard in a friendly boxing match that quickly takes an unfriendly turn.

Craig’s off-putting oddness oozes out in a way that horrifies everyone around him. He voluntarily eats soap in a bizarre humiliation ritual that makes it difficult, if not impossible, for witnesses to ever look at him again without horror and mortification, let alone maintain friendships.

Austin decides that the ego boost that comes with seeing himself reflected in Craig’s adoring eyes isn’t worth the pain and discomfort.

Friendship is an original motion picture that reminded me of plenty of other cinematic exercises in originality. As with Chuck and Buck, the central relationship has a homoerotic subtext so profound that it threatens to become text.

Though he seems unwilling to admit it to himself or anyone else, Craig seems to nurse feelings toward Austin that are more than platonic.

Austin is a dork’s conception of cool and sexy. He’s on television, has a stylish stache, plays guitar, and fronts a rock band. Craig wants to be Austin’s dear friend and confidante, but he also wants to be him.

After Austin gives him the heave-ho for his sanity and relationships, Craig fetishizes what they did together during their brief but intense friendship. He takes his long-suffering spouse to the aqueducts, then loses her in a dark, impenetrable tunnel.

It’s the finalest in an endless series of final straws for a woman who has married down more than any in cinematic history.

Friendship is a psychodrama about a very disturbed man’s disastrous attempts to make a friend as an adult that walks a fine line tonally.

I was worried that this darkest of dark comedies would veer into even bleaker territory, like two abysmal films it also resembles, Fred Durst’s The Fanatic and The Weeknd’s Hurry Up Tomorrow.

Craig’s behavior veers into the criminal and transgressive as he spirals out of control and his professional life craters along with his marriage and relationship with Austin.

Writer-director Andrew DeYoung’s comedy-drama engenders a double empathy. We empathize with Craig because his awkwardness is so relatable, but we also feel for the men and women forced to deal with the protagonist’s inability to understand anything.

In a doomed effort to bond with others, Craig keeps gushing about wanting to see a truly crazy Marvel movie. Considering the central yet tiny place Rudd plays in the MCU, this is a sly inside joke about work that obviously pays the beloved actor and screenwriter better but gives him less to work with.

Three and a half stars out of five

Tim Robinson is one of the best modern examples I can point to that serve as an argument against the pursuit of only naturalism in acting. Robinson's best work exists in two areas: awkwardly embarrassing, and untethered rage. Friendship makes great use of both of those speeds. I have no idea what a naturalistic performance from Robinson would look like, but I bet I wouldn't enjoy it nearly as much.

I heard the latest Marvel is nuts. I liked this movie a lot but if someone had pulled the fire alarm in the theater halfway through I may have never come back to it.