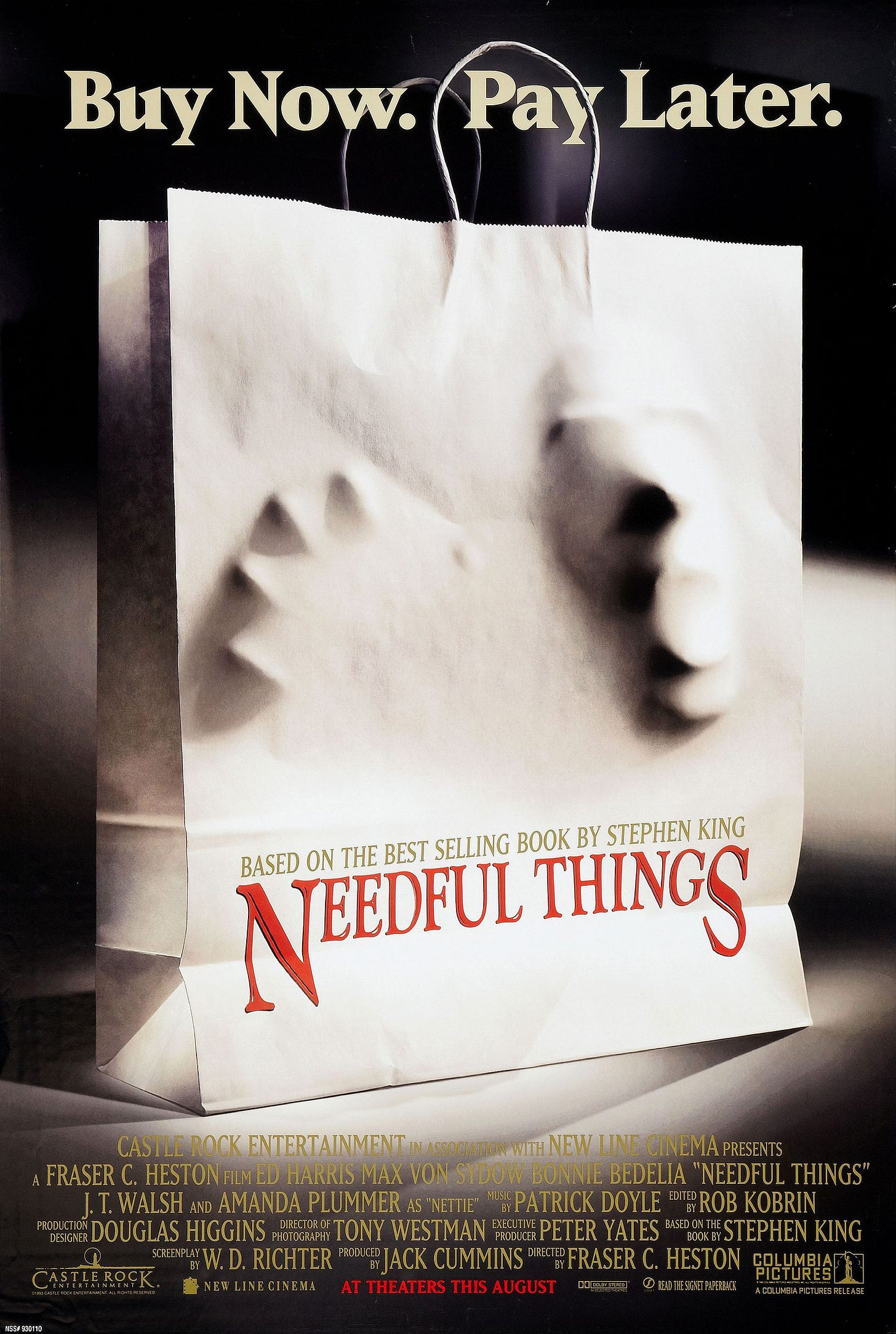

The devil sets up shop in the sinful burgh of Castle Rock in Fraser “Chuck’s Son” Heston’s gloomy 1993 adaptation of Stephen King’s 1991 novel Needful Things.

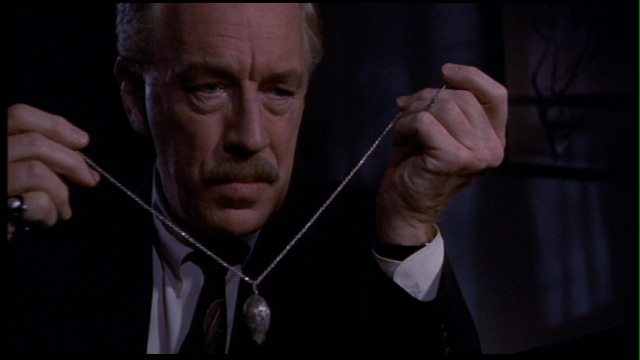

Max Von Sydow is typecast to perfection as Leland Gaunt. He’s a mysterious entrepreneur who owns an antique shop that trafficks in its customers' wildest, most poignant fantasies.

The junk shop that gives the novel and film its title sells what the inhabitants of Castle Rock, the small Maine town where many of King’s novels, novellas, and short stories take place, want most in life, but at a steep cost.

These magical doohickeys and whatnots aren’t pricey in terms of cash, but the enigmatic stranger is less interested in making money than in procuring the souls of the weak and easily manipulated.

The preeminent villain has the devil’s charm because he is evil incarnate. He deals in Faustian bargains. The small-town sinners of Castle Rock are almost too easy to control. Except for Sheriff Alan J. Pangborn (Ed Harris), an honest lawman with a moral code, they don’t pose much of a challenge for Von Sydow’s charming devil.

The small businessman with the big personality knows a suspicious amount about the residents of Castle Rock. He knows their names but also their dark secrets. The Maine town is full of secret and not-so-secret sinners with closets full of skeletons. Leland does not corrupt the innocent because no one is innocent in this dark world.

The twinkly-eyed exemplar of evil works his malevolent magic on Brian Rusk, a baseball-obsessed little boy. He sells him the Mickey Mantle baseball card of his dreams in exchange for ninety-five cents in cash and a favor.

The favor involves Brian hurling baseballs through the windows of Wilma Wadlowski Jerzyck (Valri Bromfield), a mentally ill loner prone to paranoia and incoherent rage under the best of circumstances.

I collected baseball cards as a child, so I am quietly apoplectic when a valuable baseball card is introduced in a movie or television show without a case. In Needful Things, the Mickey Mantle card is in a case, but Leland takes it out of the case to show it to Brian and then sells it to him.

My dumb brain got angry when I saw a valuable piece of sports memorabilia being handled in such a careless fashion, but Needful Things has problems beyond plot holes and inconsistencies that probably matter more to me than other, more rational human beings.

The selfish, greedy materialists of Castle Rock do not ask Leland why he wants them to perform what can very generously be deemed “pranks” against their fellow townspeople. They know intuitively that what he’s asking them to do is fundamentally amoral and destructive. They don’t care. It’s as if Leland has hypnotized the film’s foolish mortals into doing his bidding.

Castle Rock is one of those small towns where everyone knows each other. Everyone knows each other’s business. Everyone knows everyone else’s secrets. It’s a town full of conflicts and long-simmering grudges that Leland Gaunt exploits for his own ends.

Leland Gaunt has a direct line to the townspeople’s poignantly pathetic fantasies. For example, he sells a varsity jacket to a broken-down rummy whose best days are long gone, which allows him to reconnect, on a powerful and spiritual level, with the confident, successful winner he used to be before life had its wicked way with him.

These needful things are so important to their owners that they’ll seemingly do anything to hold onto them, up to and including murder.

The seeds for Castle Rock’s fiery demise were planted long before Leland Gault’s arrival, but they do not bear rotten fruit until he sets about corrupting the easily corruptible.

Needful Things suggests a more heavy-handed and less artful American version of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s controversial 1943 masterpiece Le Corbeau, or The Raven, which chronicled the madness that ensues when people in a small French town begin receiving anonymous letters alerting them to the misdeeds and crimes of their neighbors.

It also resembles the classic Twilight Zone episode “Monsters Are Due on Maple Street.” In each case, the message is that it takes very little to turn ordinary, seemingly good Americans into paranoid, angry, rage-filled monsters willing to fight their neighbors, possibly to death, if pushed too far.

Needful Things is a morality tale where pretty much everybody is ragingly amoral and consequently needs to be taught a difficult lesson about letting the actions of others turn us into our worst selves.

Human nature is ugly in Needful Things. It’s desperate, grasping, hungry and deeply suspicious. When Leland Gaunt comes to Castle Rock, home of pop culture’s most pronounced Maine accents, the ground already reeks of gasoline. All that he needs to do is light a single flame to burn the whole damn thing to the ground.

The shopkeeper deals extensively with supernatural objects like a necklace that cures the arthritis of Polly Chalmers (Bonnie Bedelia), a waitress and Sheriff Pangborn’s girlfriend, and a horse racing game that reveals the winners of actual races for gambling-addicted embezzler Danford Keeton III (J.T. Walsh), who is insultingly nicknamed “Buster” by people who hate him. In Needful Things, that constitutes everybody.

Castle Rock is full of nasty people who prioritize their own selfish fantasies over the feelings of others, but Danford Keeton III might just be the worst of the bunch.

As Tales From the Crypt has taught us, the essence of horror involves bad people being disproportionately punished for their sins and venality. That’s Needful Things.

The inhabitants of Castle Rock are an aggressively, even impressively seedy and amoral lot, more than willing to commit heinous crimes and unforgivable transgressions.

Needful Things grows progressively more shrill, melodramatic, and hysterical until a frenzied third act finds Von Sydow’s Old Country shit-starter dropping the mask completely and indulging in Satanic evil.

He no longer feels the need to control weak-minded fools indirectly. Instead, he implores his minions to do his evil bidding for selfish reasons.

Needful Things is never particularly subtle or understated, but in its third act, it devolves into madness. People don’t talk to one another so much as they scream accusations at the top of their lungs while preparing for fistfights.

Von Sydow’s otherworldly heavy conducts the violence and devastation with an evil grin and an excess of sinister guile and calculation. He’s a European demon running wild on the East Coast.

In what turned out to be the only movie Leland Heston would ever direct that did not feature his dad, the director/Nepo Baby goes overboard with darkness, literally and figuratively.

The whole movie seems to take place at night, in a storm that mirrors the gloomy machinations of its characters.

Von Sydow delivers an appropriately larger-than-life performance as the ultimate bad guy.

He has much more to work with than Harris, who is stuck with a standard-issue hero role.

Stephen King and Stanley Kubrick, or the SK Boys, as I like to call them, were not just different but antithetical. Kubrick was famously non-prolific. He made very few movies, so the movies that he made mattered. King, on the other hand, is famously prolific. He cranks out novels, novellas, short stories, and non-fiction at a steady clip.

Needful Things is, consequently, a movie that fundamentally does not matter. It’s not ambitious or audacious, but it is fairly engaging as long as you don’t expect too much.

No one’s mentioned the Rick and Morty parody with “Mr. Needful,” which twists the story around and around and around until somehow it ends with steroids and multiple vengeance beat downs

The trailer for this was a banger though, both for the heavy throes of Hall of the Mountain King and for the shots of a slow motion car wreck that I don't recall seeing appear in the film, though memory certainly could be shoddy. We had this for a couple weeks at the Oakley Drive In and aside from some backseat lovers, wasn't a lot filler.