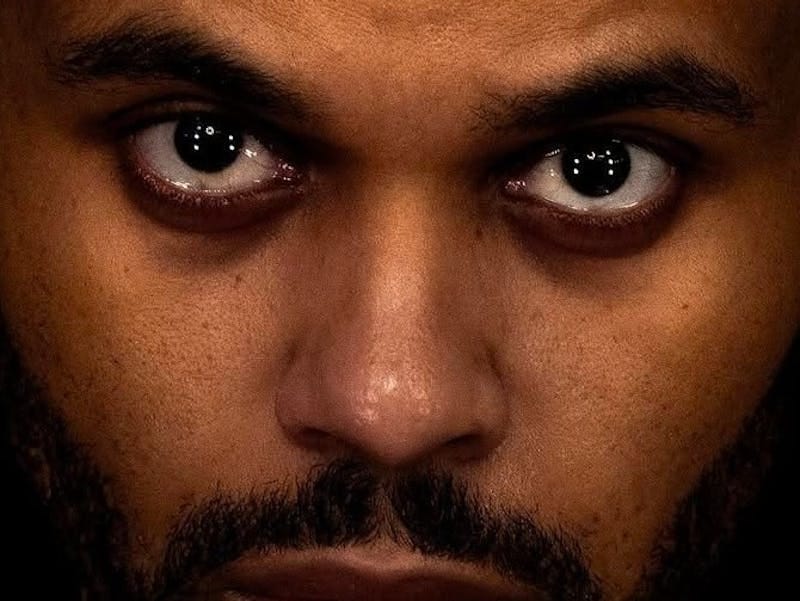

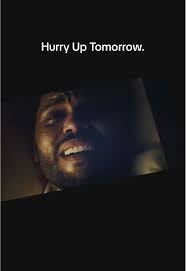

The Weeknd is a Weepy Weirdo in the Wonderfully Terrible Vanity Project Hurry Up Tomorrow

The Weeknd+Wednesday=shit show of epic proportions

You have to be very popular to play the halftime show at the Super Bowl. It’s one of the biggest gigs in the world, reserved for superstars only.

The Weeknd played the Super Bowl when he was just thirty years old. That’s insane to me. I remember thinking that the singer, songwriter, and producer born Abel Tesfaye wasn’t a big enough name for an honor otherwise reserved for legends like Beyoncé, Madonna, Bruce Springsteen & the E. Street Band, and Prince.

There are two complementary sides to Tesfaye. There’s the mainstream hitmaker whose synth-heavy New Wave pop captured the imagination of the masses. That half of Tesfaye’s personality is popular enough to play the Super Bowl halftime show.

There’s also the off-putting arthouse weirdo side of Tesfaye. I first encountered this facet of Tesfaye when I wrote up his notorious musical cult drama The Idol for My World of Flops.

The mainstream musical Tesfaye emulates the music and ethos of Prince. The other side of the musician turned actor is a Prince of pretension willing to make an utter jackass of himself in the name of art.

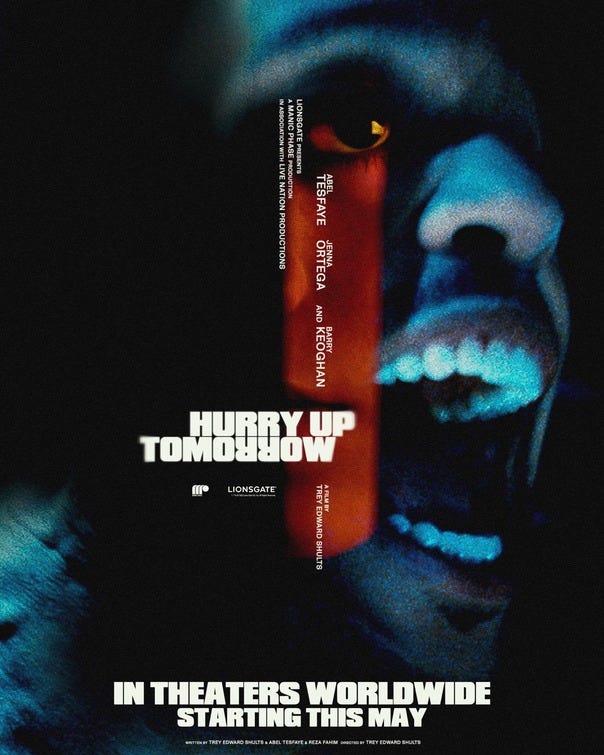

This mesmerizingly misguided component of Tesfaye finds its truest, most gloriously embarrassing manifestation in the arthouse atrocity Hurry Up Tomorrow, which spent two long years on a shelf for reasons that will be immediately apparent to anyone unfortunate enough to see it.

Tesfaye’s dual debut as a leading man and screenwriter is even more pompous than its title. How are you going to make a movie where one of the main characters is employed by a performer professionally known as The Weeknd and not make a single “Working For the Weekend” joke?

Then again, there are no jokes in Hurry Up Tomorrow. There’s no humor. There’s no levity. There’s nothing to distract from the unrelenting dourness and gallivanting grimness.

So the voluminous laughs are entirely of the unintentional variety. Hurry Up Tomorrow is so breathtakingly earnest and sincere that you can’t help but guffaw effusively at its expense.

Like The Weeknd’s music, Hurry Up Tomorrow is a throwback to the Reagan era. It suggests a deeply regrettable 1987 collaboration between Terence Trent D’Arby and David Lynch.

In terms of ambition, Hurry Up Tomorrow aspires to be David Lynch. Quality-wise, it is sub-Jennifer Lynch.

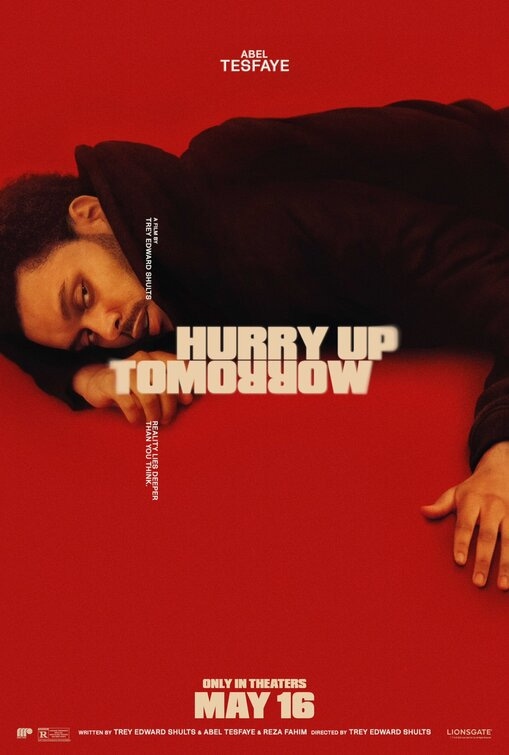

The shameless vanity project casts Tesfaye as a fictionalized version of himself. He’s a crying Canadian despondent that his girlfriend left him for being a self-absorbed jerk. The sobbing superstar is so depressed and lovelorn that he finds it difficult to concentrate on his career as a widely worshipped international icon who travels the world thrilling his millions of fans with the gift of song.

But he’s sad! He’s really, really sad. Whatever he’s doing, it’s not working for The Weeknd. The weepy weirdo tries to bury his romantic anguish with cocaine, alcohol, and random pills, but only succeeds in making himself even more miserable.

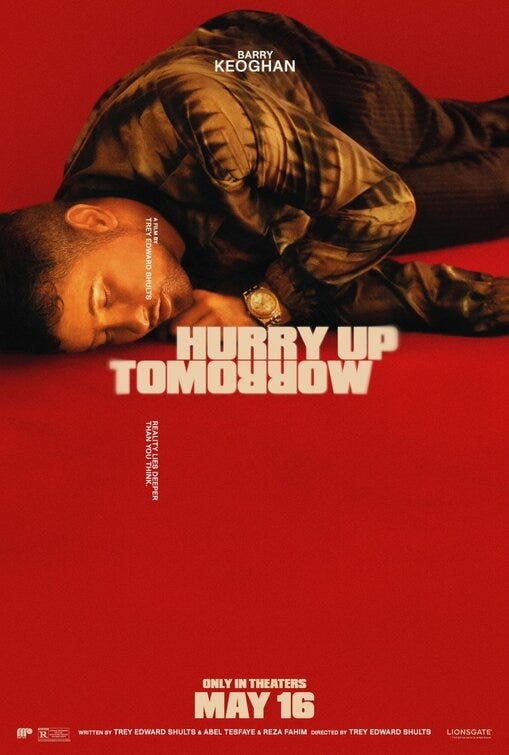

Lee (Barry Keoghan), Tesfaye’s manager, and consequently someone who is ALWAYS working for the Weeknd, wants to rouse his friend out of an extended funk to keep him from self-destructing emotionally, and because his livelihood is dependent upon his star client's ability to perform.

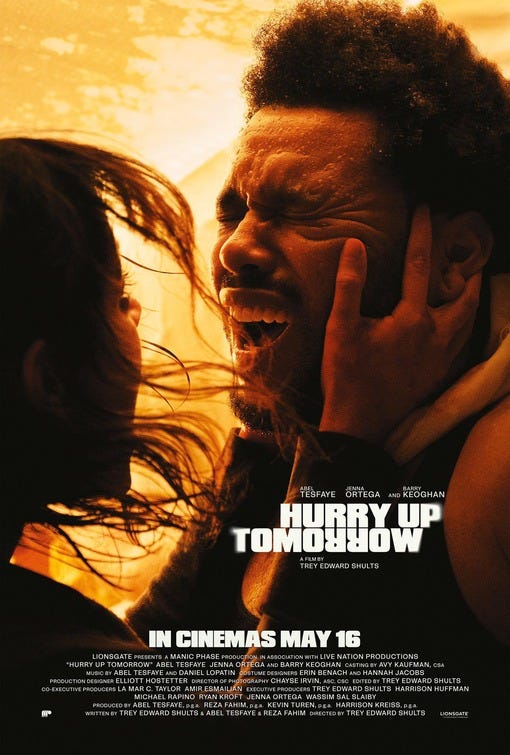

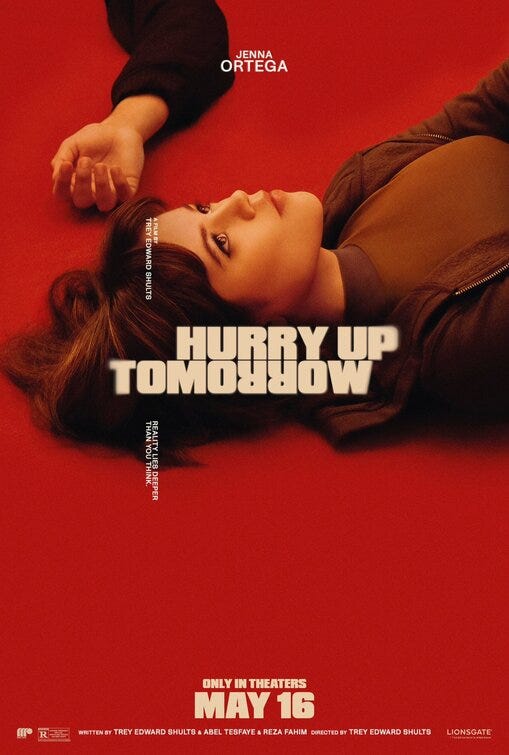

Elsewhere, Anima (Jenna Ortega), a deeply troubled Weeknd obsessive and aspiring groupie/stalker, douses a house in gasoline, then sets it ablaze.

Ortega’s fiery introduction references a Tesfaye song that figures prominently in the movie’s most gloriously unhinged scene.

It’s also a potent metaphor for what Lionsgate was doing when they bought distribution rights for the film: burning every last dollar they sunk into it because there was no way this was ever going to making any damn money at all, let alone turn a profit.

The Weeknd is thrilling his legion of adoring fans with his musical genius when disaster strikes. He loses his voice mid-concert, robbing thousands of lucky concertgoers of what would probably be the most transcendent concert of their lives.

In a massive venue, our anti-hero meets Anima when she’s fleeing security guards. It’s lust at first sight. Anima is ecstatic to be in the company of someone she clearly considers a musical genius on par with Michael Jackson or Prince.

How could she NOT fall in love with him? He’s so talented! His music means so much! It’s so deep! The Weeknd’s music is so profound that it reduces listeners to tears. It makes Weeknd cry as well. If the singer-screenwriter were paid per tear shed, he’d make more from acting than singing.

Tesfaye needs an escape. He’s also an internationally famous rock star, so he needs sex as well. Tesfaye finds both in Anima, a clearly unwell outsider who doesn’t just admire The Weeknd as a musician: she worships him as a God.

The movie also worships its star and co-writer as at least a minor deity. There’s a scene early on where Lee tries to inspire Tesfaye by telling him that he’s a legend and a god and someone whose talent is so freakishly vast and unique that he’s ultimately not even human. He’s a goddman alien, is what he is, from a galaxy far funkier than our own.

There’s no self-deprecation to go along with the endless self-aggrandizement. This isn’t semi-autobiography so much as self-mythology. Tesfaye took a look into the fractured mirror of moviemaking and was reassured to learn that he was, indeed, the fairest of them all.

After sleeping with his most ostentatiously mentally ill super-fan, Tesfaye makes a dramatic, if predictable, metamorphosis. The world’s saddest, most intense, and romantic eccentric morphs instantly into a callous womanizer who wants nothing more than for what he saw as a one-night stand to pick up on his unsubtle hints to kick rocks and leave his life forever.

His tone becomes glib and dismissive. She’s a great gal, they had a lot of fun, but he’s just not ready for anything more involved than a single evening of casual sex.

This enrages Anima. She’s naive enough to believe Tesfaye when he makes outsized declarations of affection and longing. She doesn’t understand that it’s just drunk talk and sex talk that means nothing when he’s sober and not horny.

Anima will not be denied. She refuses to be just another half-remembered sexual conquest, a perk of stardom, wealth, and celebrity.

The mentally ill young woman turns into a sexy young version of Annie Wilkes, the deranged fan turned torturer that Kathy Bates played to great acclaim in her star-making, Academy Award-winning performance in Rob Reiner’s 1990 adaptation of Stephen King’s Misery.

The movie follows suit. A ragingly, unashamedly pretentious exploration of loneliness and rock star ennui turns into a hysterical Misery knockoff.

Hurry Up Tomorrow resembles another Misery knockoff, Fred Durst’s The Fanatic, in that every choice it makes is strong and wrong. Co-writer-director Trey Edward Shults fully commits to every mistake with lunatic conviction and a hypnotic dearth of self-consciousness.

This weirdly compelling absence of self-awareness finds its truest, purest expression in a sequence so glaringly, gallingly, and gloriously insane that it quickly went viral.

Anima reacts poorly to her favorite musician cavalierly giving her the heave-ho. So she ties him to a bed so that she can bind, torture, and kill him, just like the infamous serial killer Ted Bundy.

That would be bad enough. Anima makes it even worse by delivering oral reviews of her favorite The Weeknd songs, beginning with his smash hit “Blinding Lights.”

Even well-written music reviews sound embarrassing if read aloud, and Anima won’t make anyone forget Lance Bangs.

It’s like American Psycho if Patrick Bateman subjected a bound, gagged, and terrified Huey Lewis to his thoughts about the strengths and weaknesses of his oeuvre.

The key difference is that Bateman’s weird sideline as an amateur music critic is supposed to be funny. The idea that a man with no regard for human life or laws would have extensive thoughts on the songwriting and production of mainstream pop-rock is played for laughs.

Patrick’s obsession with deconstructing pop music is satirical in both book and film form. However, that is not true here.

Hurry Up Tomorrow achieves the impossible in making Ortega, an innately cool, charismatic and attractive performer, seem like the biggest fucking dork in the world.

When Anima reviews The Weeknd’s discography while dancing terribly, Tesfaye has a look of horror and disgust that seems to belong to the actor as much as the character.

I use the phrase “actor” loosely. The Weeknd does a terrible job playing himself. He obviously knows nothing about the asshole he’s playing.

Tesfaye’s expression silently shouts, “What the fuck is going on here?” and “Who wrote this shit, and why did it make the final cut?”

The possibility that Tesfaye himself wrote the scene makes everything more morbidly fascinating.

Hurry Up Tomorrow is no mere bad movie. Its awfulness is historic and iconic. In its own way, it is a very special movie. Like Megalopolis, it’s one for the ages.

It’s fucking terrible but I’d see it again in a heartbeat. Hurry Up Tomorrow occupies a place of prominence in the great pantheon of both exquisitely, enjoyably awful movies and rock star vanity projects.

I worry that the film’s icy reception will make its co-writer/star cry, and if this movie is any indication, he’s already on the verge of crying himself to death. Hurry Up Tomorrow unpersuasively argues that he is maybe the most gifted artist of all time, so that would be a tremendous loss.

One and Half Stars out of Five

This is a great and LOL review of a flick that when the trailer played before "Sinners" my wife and I swapped stares of disbelief over how BAD it looked.

I did have a question though about this: "Even well-written music reviews sound embarrassing if read aloud, and Anima won’t make anyone forget Lance Bangs."

Hey, Nathan? Did you forget LESTER Bangs, the great, gonzo, and gone rock critic? Asking for a friend...

I feel like this movie was a gift -- to Nathan, at least. But between this and "The Idol", I have to wonder about Tesfaye's predilection for writing and portraying himself as a raging asshole. Even when he/his character is referred to as a gift to humanity, he STILL turns into a raging asshole. Usually narcissists don't ever depict themselves as "bad", so I wonder what the hell his diagnosis really is.