When Nothing But Trouble star Demi Moore became the highest-paid actress in film history after she pocketed a cool twelve and a half million dollars to star in 1996’s Striptease, she was being richly compensated for her services as an actress. Moore was being rewarded for the robust box office of smash hits like 1990’s Ghost, 1993’s Indecent Proposal, and 1994’s Disclosure, for being one of the biggest female movie stars in the world, if not the biggest.

But Moore was also being paid more money than any actress had ever been paid up until that point for her body. More specifically, she was being paid a fortune to do the extensive nudity promised by the film’s title and premise.

Americans are prudes and perverts, so we had no problem shamelessly ogling Moore’s naked form while simultaneously judging her and the film for being raunchy and risque.

There was an awful sense that Moore must be punished for so blatantly inflaming our collective lust. The film’s abysmal box office and dreadful reviews are attributable in part to the satire’s muddled and unfunny tone but also a puritanical need to punish Moore for being too sexy.

By that point Moore had been getting naked on film for over a decade. It began, horrifyingly enough, with 1984’s Blame It On Rio, a notorious remake of a French film about a middle-aged man who is seduced by his best friend’s horny 17-year-old daughter.

Thankfully, Moore did not play the frequently naked seventeen-year-old. That role was instead played by Michelle Johnson, who was seventeen when the film was made and had to receive permission from a court to perform nudity onscreen.

Moore instead played the best friend of the 17-year-old, whose sexual fling with a man old enough to be her father is treated by the film as an amusing lark. Moore was thankfully of age when she made the film, but that didn’t make the enterprise any less creepy.

Blame It on Rio was less a traditional sex comedy than a sex crime. Moore went on to become a preeminent sex symbol of the 1990s. She made history and headlines when she appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair naked and pregnant.

Even when Moore was not overtly sexualized, as in Indecent Proposal (where a rich man is so obsessed with her body that he offers to pay one million dollars for a night with her) and Disclosure (where she uses her body and sexuality to terrorize poor, blameless Michael Douglas) her body and physicality still took center stage.

In 1997, a mere year after Striptease, Moore played the first woman to undergo training to join a Navy SEAL in G.I Jane. The emphasis remained on Moore’s body and its ability to withstand pain and exhaustion.

Incidentally, I heard from Chris Rock that they were making an extremely tardy sequel to G.I. Jane, starring Jada Pinkett Smith, at the Oscars a while ago. The project must still have been in early development, however. Will Smith was apparently so worried about jinxing G.I. Jane2 that he took the unusual step of slapping Rock hard on camera for his transgression.

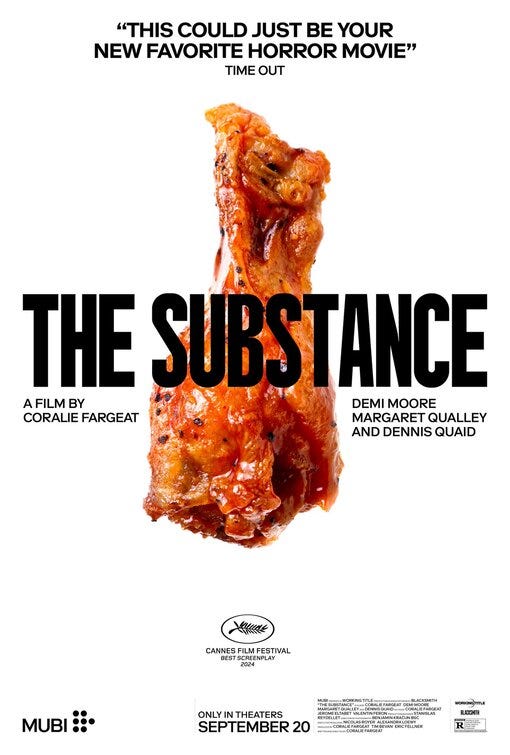

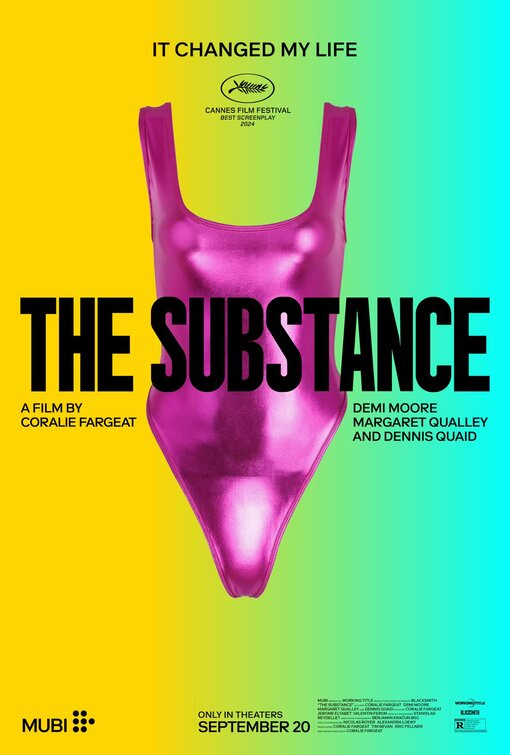

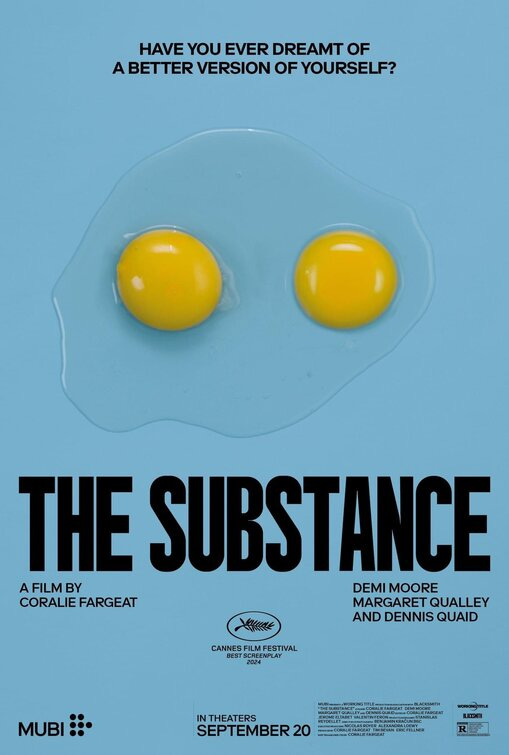

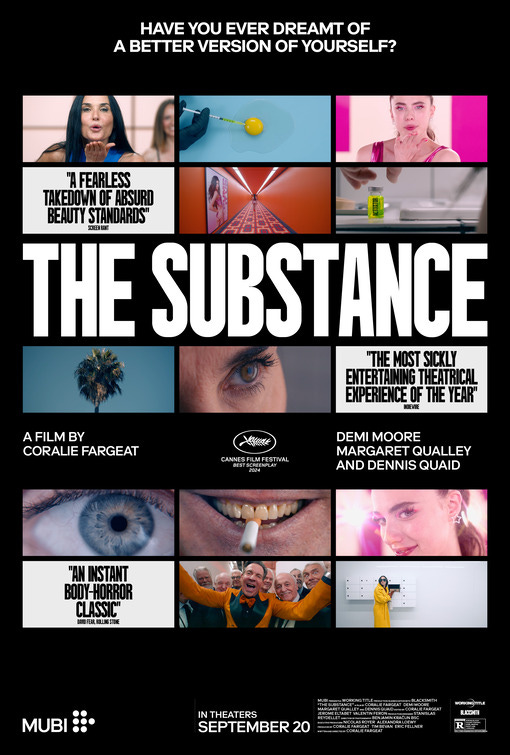

Moore consequently brings enormous baggage to the impossibly demanding role of Elisabeth Sparkle, a legendary actress and the host of an aerobics show.

Elisabeth is already self-conscious about her body and her age when asshole producer Harvey (Dennis Quaid in a manic cartoon turn redolent of his kooky take on The Killer in Great Balls of Fire) fires her for the unforgivable crime of turning fifty.

Moore’s tortured anti-hero/villain will do anything to turn back time and return to an era when she was beautiful, worshipped, and wanted. So when she learns of The Substance, a serum that can transform her into a younger, more beautiful, and more perfect version of herself, she’s onboard despite everything that seems sinister and wrong. She thinks it will change her life. It does, but not for the better. Like the title of Moore’s best-loved film, the Substance gives her nothing but trouble.

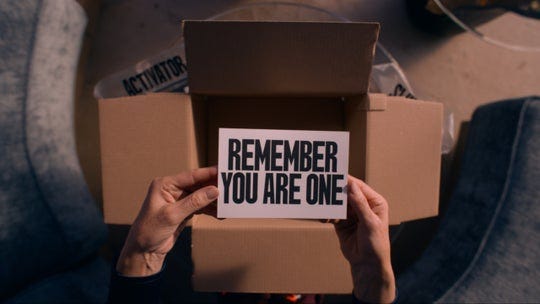

Elisabeth knows nothing about the process except that she must alternate weekly between being Sue, an impossibly gorgeous, twenty-something sexpot played by Margaret Qualley, and her fifty-something self. She’s sternly informed that she must never forget that she and her younger version are the same, that they are one person with two bodies.

The Substance is a Cronenbergian waking nightmare even when it is working. Sue’s perfect body and perfect face emerge out of Elisabeth’s comatose physique.

Sue is everything Elisabeth has ever wanted to be and more. She enters into what is clearly a Faustian bargain with an organization that cannot be anything but evil and destructive because youth, beauty, and success matter to her more than anything else, including her happiness and mental health.

Elisabeth becomes addicted to being Sue. It’s a high she can’t quit. It doesn’t just alleviate her depression and existential angst over getting older; it makes her ecstatic. It fills her with joy. It is everything to her and more.

The more time she spends in Sue’s flexible young body, the harder it becomes to live life as a fifty-year-old has been, particularly once parts of her body begin aging unexpectedly.

Elisabeth is the victim of a crazy-making world and industry ready to hurl women in the circular file once they hit menopause. The Substance either induces or exacerbates her mental illness.

Though the ominous forces behind The Substance insist that she and her younger self are one, it isn’t long until she suffers a psychic split. Elisabeth develops a form of schizophrenia. She begins hating her younger self and seeing her as something both foreign and threatening.

As Elisabeth continues to unravel emotionally and Sue’s television career explodes solely on the basis of her youth, sexiness, and charisma, she begins to change on a physical as well as psychological level.

The Substance takes a nifty Black Mirror/ The Twilight Zone/Tales From the Crypt premise in an unmistakably Cronenergian direction. Writer-director Coralie Fargeat channels Stuart Gordon at his most stomach-churningly intense as the film embraces body horror.

Fargeat favors extreme camera angles and wild close-ups. She shamelessly objectifies Qualley’s body in a way that would prove much more problematic if she were male. Being a woman making a blunt satirical point about the objectification of women and the price we pay, individually and collectively, for seeing women only as objects gives her more leeway to blatantly objectify the radiant young actress, who has a perfection that seems impossible.

The filmmakers wisely eschew the soullessness of CGI in favor of the artisanship of practical effects. The gore here is of tremendous quality and quantity. The Substance is a lot. It is, in fact, deliberately too much. Every time I thought The Substance had gone as far as it could go and could not get any more extreme, it proceeded to get even more wildly, deliberately excessive.

Moore delivers a fearless performance that embraces not just ugliness but Lovecraftian horror. The Substance offers a uniquely visceral take on Beauty and the Beast mythology, where beauty is the beast and the beast is a beauty.

The Substance has strong echoes of Carrie, From Beyond, The Shining, and many other iconic horror classics, but with a subversive feminist twist.

I’m glad that I saw The Substance on the big screen. It wasn’t just a movie. It was an experience. It affected me deeply. Like Colour Out of Space, The Substance is a great horror film too intense and punishing to see twice. Also like the acclaimed Lovecraft adaptation, it’s not a fun experience by design.

The Substance is so fucking disgusting that it made me want to puke my guts out. I mean that in the best possible way. I can’t wait to see what the director does next. Hopefully, that’ll also make me want to wretch in disgust/appreciation.

Four stars out of Five

Seeing this in a packed theater was one of the greatest movie experiences of my life.

Saw this last night with a fairly full house, and I'd say fully a third did not know what they were in for. Behind me, a group of people (who I'm guessing were probably chemically altered for the experience) laughed uproariously as the film went on, like they were watching Young Frankenstein or, oh, I dunno ... Showgirls? It didn't quite ruin the experience, but they were guffawing directly at the back of my head and I wish I could do to them what happens to the audience in The Substance.

BTW, if there's a film criticism hall of fame, I nominate "Like the title of Moore’s best-loved film, the Substance gives her nothing but trouble." for zinger of the year.