Steve Allen Rants Angrily About Trashy Pop Culture From Beyond the Grave in 2001's Posthumously Released Vulgarians at the Gate: Trash TV and Raunch Radio – Raising the Standards of Popular Culture

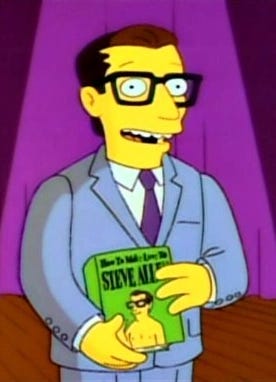

Steve Allen wrote many books. This is certainly one of them

When Steve Allen’s Vulgarians at the Gate: Trash TV and Raunch Radio—Raising the Standards of Popular Culture was published in 2001, it was not a howl of rage at the vulgarity and tastelessness of contemporary pop culture from a legendary figure at the end of an auspicious life and career.

When Vulgarians at the Gate was published on April Fools Day, 2001, Allen was dead. The book was released posthumously. When his final book was released, Allen was an angry ghost ranting at a world he no longer understood and that would not listen to him from beyond the grave.

In Vulgarians at the Gate, Allen posits himself as a culture warrior leading the charge against an overwhelming tsunami of child-corrupting and society-destroying sex, violence, vulgarity, profanity, and all-around ugliness.

“My purpose in writing this book, therefore, is to provide responsible adults with the ammunition they need to wage a successful cultural war for the attentive consciousness of America’s children,” Allen writes.

The prolific Rennaisance man is convinced that the people in power at studios, television networks, advertising agencies, and the media are fundamentally like him.

“Among those who once formally guarded the moral and ethical ramparts were the corporations, consisting chiefly of men who had been reasonably well-educated and were by-and-large responsible citizens—the conservative country club set, in other words—but their role as moral guardians now appears to be almost totally abandoned.

Corporate America, granting exceptions, has not only largely given up its former admirable participation in the maintenance of society’s general sanity but has joined those who would undermine it and is, in fact, funding them in large measure,” Allen pontificates stiffly.

Allen felt that if he could only get the attention of the country club set that serves as cultural gatekeepers and lay out his argument in depth, he could either shame them into doing the right thing or persuade them using logic, reasoning, and an appeal to their better angels.

The original host of The Tonight Show sees these powerful people as peers. They’re reasonably well-educated (no high school dropouts in the corporate suites!), responsible citizens who belong to country clubs, vote, are faithful to their wives, and keep their lawns tidy.

Yet when these otherwise responsible and respectable gentlemen (in Allen’s mind, they’re all gentlemen) go to work, these members of the Conservative Country Club set participate in the destruction of Western culture and the corruption of children.

In Allen’s mind, these misguided souls are motivated by greed, self-interest, and anxiety about losing their positions of power and privilege, but also because there isn’t a stigma related to being involved with violent, vulgar, or sexually explicit entertainment.

Allen wants to change that. He wants to shame influential people he holds responsible for entertainment, which he considers evil, not just socially irresponsible.

He accomplishes this partially by sending angry letters to people he considers crude or amoral.

“Never underestimate the power of a responsibly worded letter of complaint or criticism,” Allen writes hopefully to an audience already in the habit of sending out angry letters when something displeases them.

Vulgarians at the Gate is filled with letters the author sent to people he holds responsible for the sad state of our culture.

In a particularly ridiculous example, Allen attends a diner party where he is horrified to learn of a Grey Poupon commercial built around a plastic mustard bottle that sounds like flatulence when squeezed.

This offends Allen’s bourgeoisie sensibilities so much that he wrote an indignant letter to the CEO of Nabisco that reads,

“Dear Mr. Greeniaus:

At a recent dinner party, a number of guests—most of whom work in the entertainment industry—were talking about the degree of truly disgusting material that is now a matter of daily annoyance on television, radio, and in motion pictures. I emphasize that this was no meeting of the Moral Majority but involved just plain show-biz folks, most of whom—I assure you—are revolted by a good deal of what we presently see on the air or in film.

Someone present asked me if I’d seen the latest Grey Poupon commercial in which the “humor” was based solely on the factor of breaking wind. Given that nature herself has provided a means by which the normal human response is disgust, I take it the point does not have to be debated. I actually thought they were joking when they mentioned that the Grey Poupon brand of mustard had a new commercial guilty of such a lapse of taste.

To my astonishment, I saw the commercial last evening.

In connection with a commentary on the matter that I’m planning to do, I’m writing to give you the opportunity to comment. Was the decision to produce and subsequently telecast this particular commercial something that was brought to your personal attention and approved by you? If not, does it nevertheless now strike you that the commercial was a perfectly marvelous idea?”

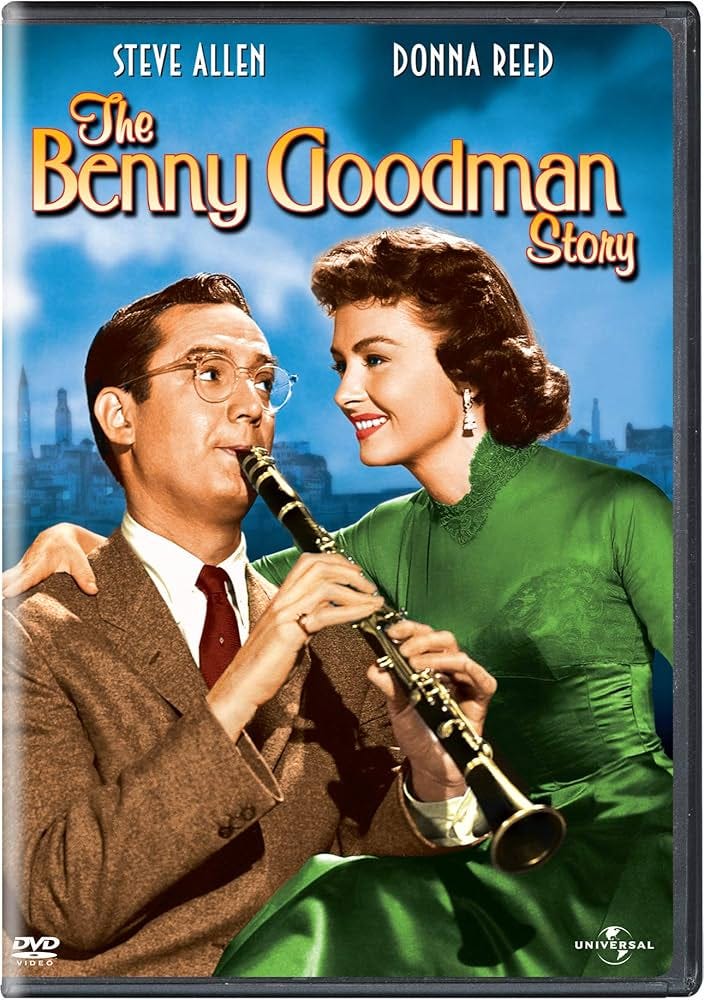

Though you would not know it from Vulgarians at the Gate, Allen was not a Republican or a devout Christian. He was, instead, a Democrat, a humanist, and an important artist in myriad fields, including literature, poetry, song, jazz, songwriting, and talk shows.

Yet when Allen rails wordily against the purveyors of smut and sleaze, he sounds exactly like an Evangelical Christian trying to protect the innocence of children.

Allen wasn’t racist, sexist, or homophobic, yet, with the notable exception of Shasta McNasty, I cannot help but notice that the subjects of Allen’s incandescent rage are almost uniformly black, Jewish, or women.

Out of concern for the more delicate sensibilities of the fairer sex, he rails against Sex and the City, a show he is mortified to learn, deals with such issues as “penis size, oral and anal sex, and how a sudden onset of flatulence can destroy a romantic interlude.”

Because he is a lovely man, Allen assumes that Sarah Jessica Parker is a good person and is consequently aghast at Sex and the City’s sexual content. Instead, Allen holds HBO and Sex and the City’s gay, Jewish creator Darren Star responsible for everything that makes the show vile and forcing a nice lady to say unladylike things about dongs and boobs and whatnot.

Allen devotes an entire chapter to Madonna. He acknowledges that she’s a stale topic for moral condemnation, particularly in 2001, a decade and a half removed from the era when she first shocked and titillated an intrigued and aghast public, but he can’t help himself. She’s just SO vulgar! She’s all about pushing the envelope, a phrase that, to Allen, is pure evil.

The author devotes SIXTEEN PAGES to an exhaustive transcription of Madonna’s infamous appearance on Late Night With David Letterman. This is not necessary. A brief recap would have done the trick, but Allen wants everyone to know that a famously vulgar pop icon is guilty of myriad offenses against good taste.

Allen rages the potty mouth of Andrew “Dice” Clay, who he confusingly refers to as a hot kid comic when he was a forty-four-year-old show-biz veteran when the book was released.

The prolific entertainer wags an angry finger of accusation in Jerry Springer’s direction and is offended by the foul-mouthed hosting gigs of Whoopi Goldberg and Rosie O’Donnell.

Allen insists that in the good old days, “Hosts were generally chosen for their air of authority and dignity and encouraged to officiate the proceedings with an appropriate degree of decorum.”

Ah yes. Nothing is more dignified than hosting the Golden Globes.

Allen holds many accountable for the unforgivable ugliness of pop culture, including entertainment executives, the advertising industry, parents, permissiveness, excessive tolerance, and critics afraid to call out the lewd immorality of pop music.

The veteran entertainer insists that a misplaced sense of ultra-tolerance on campuses is so rampant that ten to twenty percent of college students “refuse to say that the Holocaust is morally wrong.”

That might seem hard to believe or implausible until you consider that 127 percent of statistics are bullshit made up on the spot.

In Allen’s mind, the role of a critic is to agree with him and his conception of pop culture as a contemporary Sodom & Gomorrah, sending our country and culture on a bullet train to hell.

To Allen, a critic's job is to judge entertainment on morality. To him, it is a critic’s sacred duty to cast unstinting judgment on vulgarians who degrade our culture. In the late raconteur’s opinion, critics must also compare the music, movies, and books of today to the greatest art of the past.

In a representative passage, Allen argues, “In the 1950s and 1960s, there were hundreds of music critics in their middle years who had no doubts whatsoever that Cole Porter, let’s say, was vastly superior at the song writing art to Mick Jagger, for instance. Why, then, did they rarely say as much? I submit the reason was a sort of social cowardice. The critics, though they knew better, held their tongues because they did not want to seem unhip.”

As someone who has written about pop culture for nearly thirty years, I can say with conviction that the reason that critics didn’t unfavorably compare Mick Jagger to Cole Porter isn’t out of a fear of appearing unhip but rather because the comparison makes no sense. It’s a false equivalency. This isn’t apples and oranges; it’s apples and hydrogen bombs.

Comparing new music to Cole Porter would be like comparing every movie I write about to Citizen Kane. It’s akin to complaining that while the latest Taylor Swift album is catchy and well-produced, nothing in it is as moving or as masterful as Ella Fitzgerald’s rendition of “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.”

Is that true? Of course. It also says nothing about Taylor Swift or “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.”

Allen at least considers Jagger’s writing lyrics. In a predictably tone-deaf section on hip hop, the prolific poet, songwriter, and jazz musician determines that “rap” isn’t even music!

“First of all, whether one favors or dislikes it, the genre, properly speaking, cannot be referred to as music at all, given that music has always been defined as involving melody and harmony,” Allen sourly states.

Rap isn’t music. Rap? More like crap! Allen continues his old white guy condemnation of rap by insisting, “As a lyric writer myself, I hesitate to consider such material as lyrics at all, given the noble tradition through the years of such true artists of the trade as Johnny Mercer, Ira Gershwin, Dorothy Fields, Stephen Sondheim, Joni Mitchell, and scores of others.”

Can a “rapper” really consider himself a musician or a lyricist if they are not carrying on the proud tradition of Cole Porter, or Stephen Sondheim? Or is that setting the bar a little too high? I think Ludacris is a great rapper and a terrific lyricist but even I must concede that he’s not as good a songwriter as George Gershwin.

“Move Bitch” is a fun, energetic song, but it does not reach the creative heights of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Allen isn’t a total hater. “Some of the dancing associated with its presentation is both original and inventive,” he allows, and the beats are infectious, but he concludes, with his trademark air of sour judgment, “Even in the case of young African Americans, who at least have a clear-cut and definable problem to address, an examination of hip hop and rap lyrics as they might represent a form of social protest suggests they are remarkably devoid of specifics. Killing policemen and raping women of whatever color is obviously not an intelligible form of political protest. It is, in fact, a recipe for disaster.”

Allen wants you to know that he is not speaking solely for himself but rather for Milton Berle, Shecky Greene, Jack Carter, Henny Youngman, and plenty of other Friar’s Club members who peaked during the Truman era and now look at contemporary pop culture with anger, disgust, and confusion.

Sickos today might act like profanity is an essential component of comedy, but Allen reminds us that Amos and Andy didn’t need to engage in potty talk to make people laugh. Amos and Andy relied upon racist caricatures, not swear words.

The people who made Citizen Kane and Casablanca didn’t resort to violence or explicit sex to hold an audience’s interest, and Will Rogers delighted Americans without ever using phrases like bitch, slut, whore, motherfucker, or cocksucking motherfucking piece of shit son of a whore.

Maybe we should all follow the examples of entertainers who thrived in a much different era and have been dead for ages instead of letting greed and a lust for power dictate the entertainment our precious children consume.

Oh, won’t someone think about the children!!!

I’m doing final revisions for The Fractured Mirror, my epic upcoming book about the long, fascinating history of American films about moviemaking.

I’m refining this beast of a book until it cannot be refined any further and is as good as it can be. Much of this work consists of cutting words. Every draft is shorter than the last, so I am particularly attuned to inefficient writing.

Allen never says anything directly when he can be unnecessarily wordy and involved. To cite a particularly egregious example, late in the book, Allen writes, “A person with even moderate intelligence should have been able to recognize that such nuggets of wisdom as “Don’t listen to anybody over thirty” may accurately be described as stupid, as may the advice to “Do your own thing,” without regard to whether that thing is wise, virtuous, or constructive on the one hand or idiotically destructive on the other.”

There are fifty-nine words in that passage. The vast majority contribute nothing. They just take up space in a book that could easily be half as long, or, alternately, an impassioned magazine article in a publication targeting the old and out of it.

That fifty-nine-word passage could be cut down to sixteen words (“The aphorisms “Don’t listen to anyone over thirty” and “Do your own thing” are stupid) without losing anything essential.

Also, Vulgarians at the Gate was published in 2001, thirty-seven years after activist Jack Weinberg introduced the phrase “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” into the cultural lexicon, but this is unmistakably a book out of time by a man with an exceedingly shaky grasp on contemporary pop culture.

Allen unwittingly provides his sad postscript when he concedes, “Ten years down the line, our popular culture may be even more degraded than it is at the present. In that case, ultimately, my efforts here may be of interest chiefly to social historians.”

It’s been just under twenty-four years since Allen’s manifesto was published. In that time, popular culture degraded to an extent that would undoubtedly drive Allen insane. His brain would explode, Scanners-style, upon learning that social conservatives all lined up behind a man whose most famous public utterance involves bragging about aggressively fondling female genitalia.

As Allen feared, his efforts primarily interest pop culture historians like myself.

The vulgarians who rule and ruin pop culture represent a terrifying and formidable foe for moralists like Allen. Thankfully, he wields the most incredible power of all: the ability to annoy relatives, friends, coworkers, and strangers with unwanted photocopies.

Late in the book, Allen writes, “Another thing the reader concerned about American moral behavior can do is to distribute relevant literature. Many newspapers and magazines are now supporting the cause of both common sense and general decency. If you encounter such a feature, consider making copies of it and mailing, faxing, or e-mailing it out to friends and associates. It is possible to reach an impressive number of people by such a simple method.”

Tragically and surprisingly, senior citizens faxing smudgy Xerox copies of a Michael Medved article about violence in children’s movies to disinterested relatives, clergy, and politicians failed to bring about the social change Allen desired.

That hasn’t kept countless well-intentioned but clueless seniors from following his example.

That makes Allen’s old man rant poignantly pointless. Allen tried to make a difference. He tried to make the world a more civilized place. He failed.

But at least he tried.

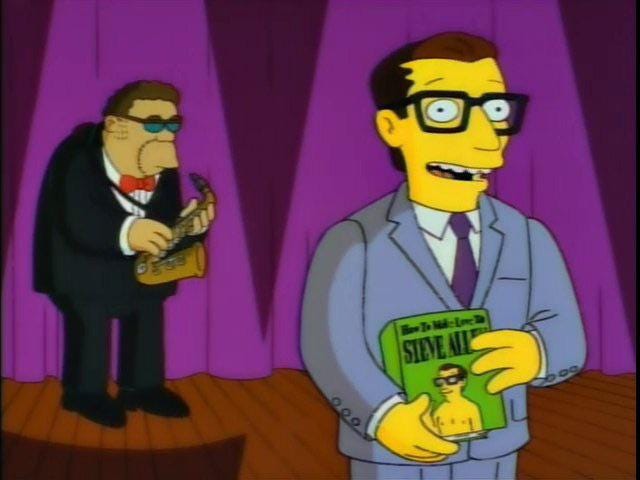

Me love Simpsons writers' fixation on Steve Allen, and "if this is anyone but Steve Allen you're stealing my bit" might be best-written joke in entire history of show.

I think it's some sort of comedy Inception that one of Steve Allen's most notable bits (from back when he used to actually do comedy) was reading made-up "letters to the editor" from indignant morons waxing hyperbolic about something mundane or pointless...and then he BECAME one of those people who wrote such letters unironically.