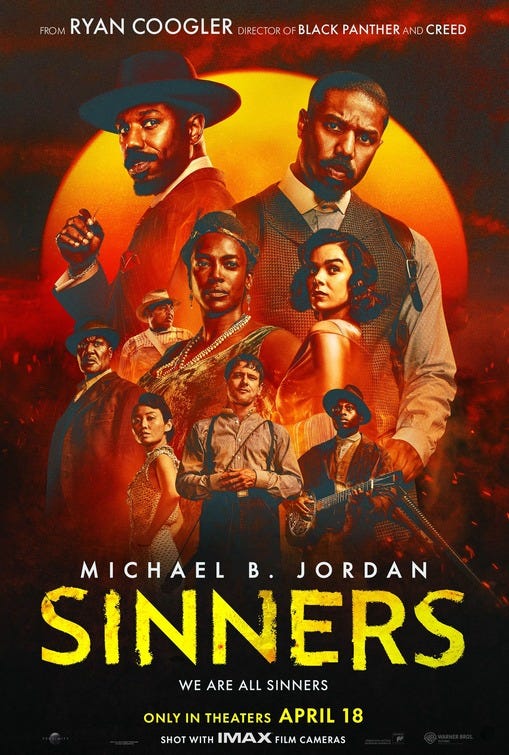

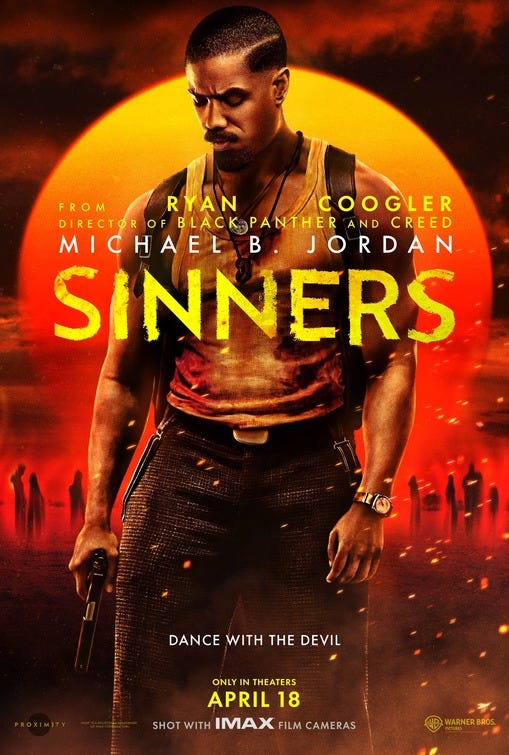

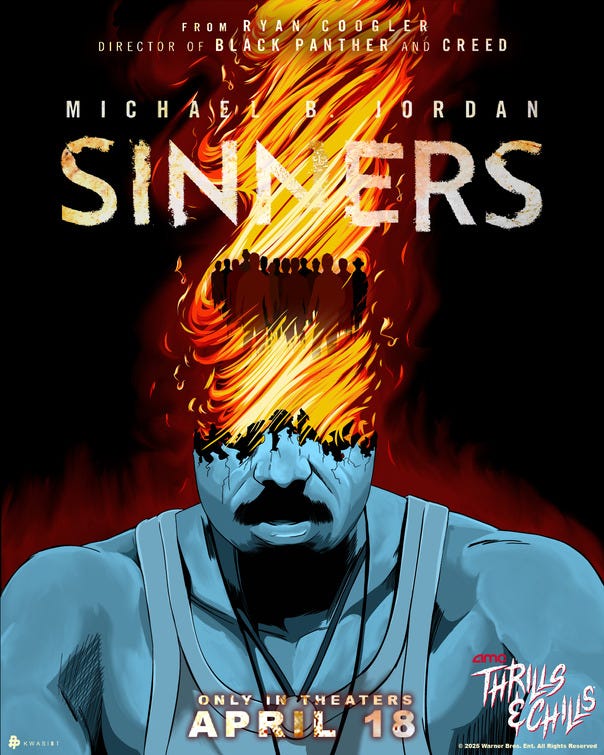

Ryan Coogler's Riveting Sinners Has a Seedy Blaxploitation Premise and Arty New Hollywood Execution

It's Leadbelly by way of From Dusk Til Dawn

As someone who loves horror movies more than any other genre, with the possible exception of comedy, I have complicated feelings about the idea of Elevated Horror.

There’s something snooty and high-falutin’ about a concept that separates fright films with ambition and artistry from run-of-the-mill schlock that traffic in jump scares, gore, and gratuitous nudity and violence.

At the same time, I will be the first to concede that a lot of horror movies fucking suck. Before Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, the last horror movie I watched and wrote about, for The Fractured Mirror, my upcoming book about American movies about filmmaking, was a 1996 abomination called Santa Claws about a lunatic obsessed with a scream queen played by Tromeo & Juliet’s Debbie Rochon who dresses up like Santa Claus and murders people close to his object of affection with a metal claw.

It’s somehow much worse than that uniquely unpromising description suggests. It was written and directed by John A. Russo, a novelist, screenwriter, and director who co-wrote the screenplay for Night of the Living Dead.

Russo includes a poster for the 1968 horror classic as a cheeky in-joke. Judging from Santa Claws, George Romero is one hundred percent responsible for Night of the Living Dead’s greatness.

Sinners and Santa Claws are both horror movies. One barely qualifies as a movie, while the other is an arthouse stunner with a B movie soul.

Writer-director Ryan Coogler’s inventive bloodbath is the mash-up of Leadbelly and From Dusk Till Dawn we never knew we needed.

Sinners exists on a higher evolutionary plane than Santa Claws. It’s one of the most audacious and ambitious horror movies in recent memory. Hell, it’s one of the most audacious and ambitious movies in recent memory, regardless of genre.

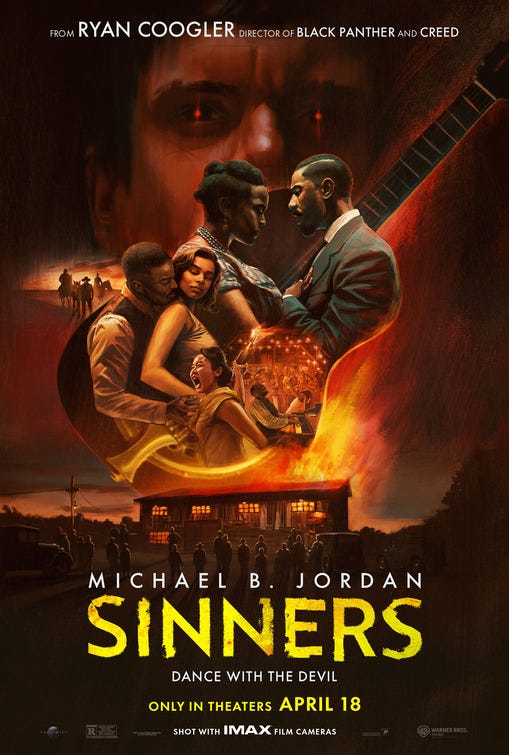

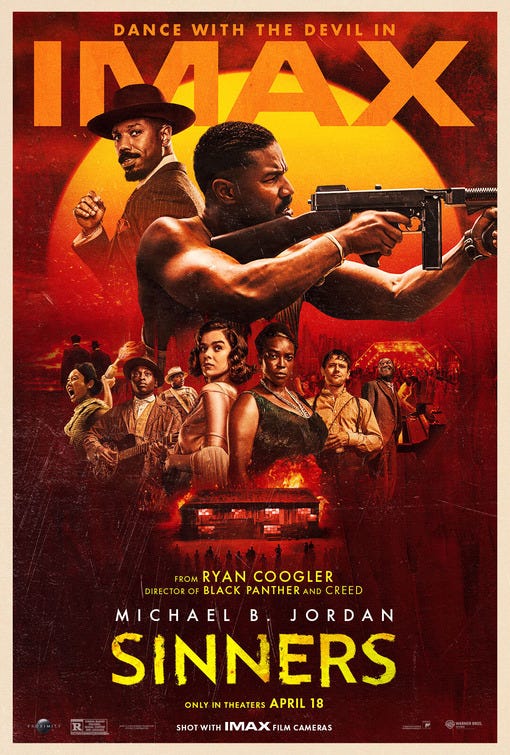

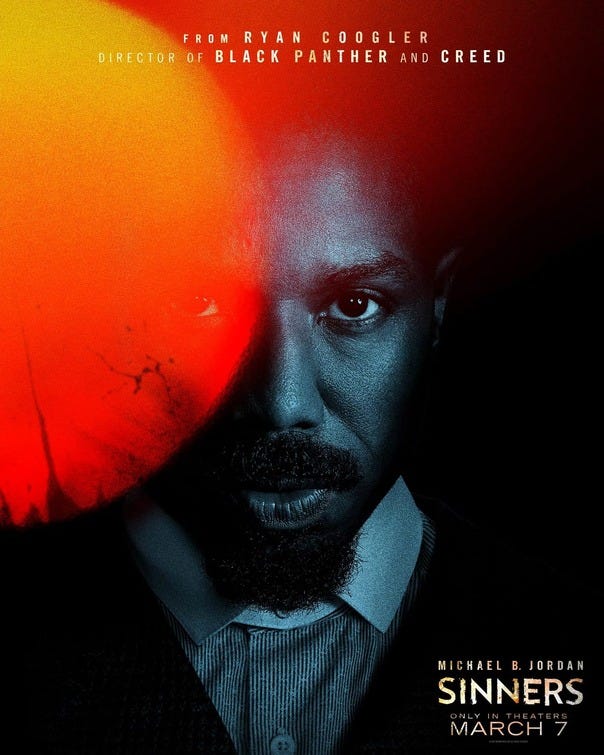

In a stunning dual performance every bit as mesmerizing as his turn in Black Panther, Michael B. Jordan portrays Smoke and Stack, twin brothers who fought in World War I before leaving the Delta for Chicago to pursue careers in gangsterism and thievery.

After seven years in the Windy City, the twins return to their hometown with suspiciously, conspicuously vast sums of money with an eye towards turning dirty cash into a respectable business.

That’s the American dream: to follow in the footsteps of the Kennedys and go from being a bootlegger to an American political dynasty in a generation or two.

The vehicle for the brothers’ ambitions is a saw mill that they want to turn into a juke joint catering to the black community.

The impeccably dressed, charismatic hustlers use their ill-gotten fortune to hire the people necessary to turn an empty structure into a boozy, sexed-up juke joint.

They then set about using their substantial financial resources to convince skeptical collaborators to help them transform an old mill into a hotspot in just a few hours.

That’s an ambitious timeline, but Smoke and Stack have the savvy, magnetism, power, and money to convince people to do what they want, when they want, and how they want.

Music is central to the film and the club. The twins pay hotshot harmonica player and pianist Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo) enough to skip his longtime gig and work for them. They convince cousin Sammie Moore, (Miles Caton) a guitar-picking musical prodigy, to defy his preacher father and perform at the debauched opening night of their club.

In a world where originality and audacity are punished harshly, Coogler has the testicular fortitude to take the kind of crazy chances that lead both to great art and spectacular disasters.

The film is never more gutsy than during a surreal set-piece where the juke joint, where much of the action takes place, falls into a time warp, and the past and the present take on a physical form.

The blues is so powerful that it rips a hole through the fabric of time, and our revelers are joined by musicians from Africa’s past in the form of griots and Black America’s future.

Time becomes elastic, and Sammie is joined by an acid rocker in the Jimi Hendrix mold, B-boys breakdancing, and rappers practicing an art form that would not exist for decades yet has its roots in the rich, deep history of black music, black culture, and black pain.

It’s the kind of risk that fills studio executives with dread. Few things scare studios more than originality and risk, and this sequence in particular is both original and very risky.

If Sinners were not an immersive masterpiece, this unexpected simultaneously leap into the future and the past would be distracting, if not downright embarrassing. It would take you out of the movie. I can only imagine how many focus group respondents wondered why the fuck rap and breakdancing were featured in a film that takes place in 1932.

It’s fucking nuts in the best possible way. It’s also the kind of thing that fills studio executives with cold dread because it dramatically expands the film’s grim yet vibrant fantasy world.

Sinners has a time warp quality as well. It may be a film from 2025 set in 1932 that trippily travels forward and backward in time, but it also has an unmistakable 1970s vibe.

Coogler’s audacious terror tale has a seedy blaxploitation premise—sexy black Southern gangsters square off against bluegrass vampires—with New Hollywood execution.

Like From Dusk Til Dawn, Sinners doesn’t become a proper horror movie until deep into its runtime. It’s so compelling as a historical drama about the complex racial and power dynamics of the Prohibition-era South that it doesn’t need to be a horror movie to be a wholly satisfying cinematic experience.

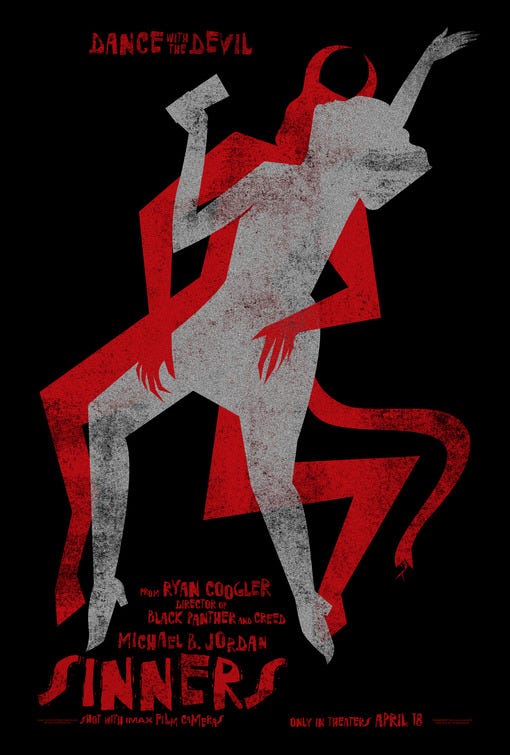

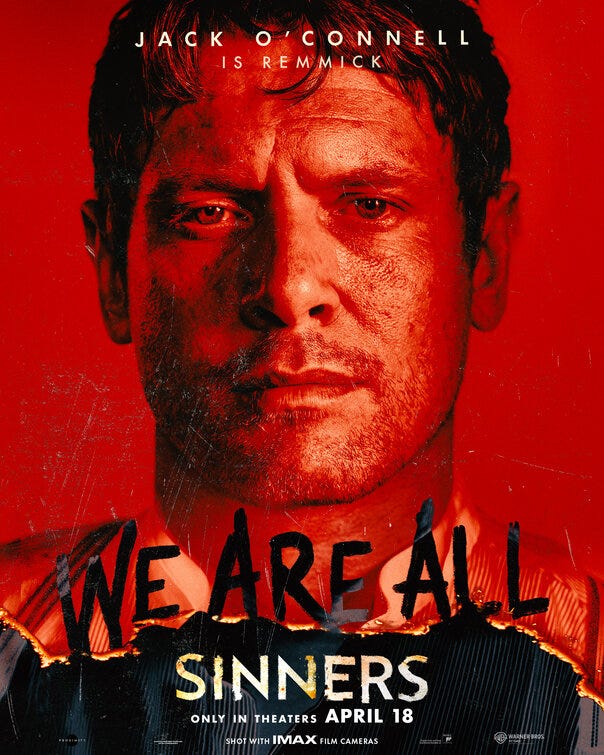

Supernatural evil arrives at the juke joint in the form of Remmick (Jack O’Connell), a mysterious folk musician and vampire with a brogue that is at once folksily charming, and sinister, yet playful and chilling.

The extremely white man shows up at the juke joint with a husband and wife, requesting entrance.

Sinners is an atypical film in many ways, but it is traditional in its portrayal of vampire lore and mythology.

The vampires cannot enter the juke joint of their own accord. They need to be invited in.

Merrick lurks ominously just outside the hastily assembled club, waiting patiently and biding his time.

It wouldn’t take much to turn Sinners into a proper musical. It’s halfway there already, thanks to the central role music plays in the proceedings. Sammie’s ferocious talent has preternatural consequences but the blood suckers are no slouches when it comes to performing either.

There’s a wonderful scene where Merrick and his undead companions play a folk song and the black revelers have to concede that they’re damn fine musicians as well as inhuman ghouls.

There’s an incongruous joy in the vampire’s celebratory music and dancing. Merrick may be evil incarnate and a creature from the bowels of hell, but he likes to sing, he likes to dance, and he likes to have a good time.

In a lesser film, the introduction of bluegrass, Irish-dancing vampires as the antagonists would inspire unintentional guffaws.

Sinners’ willingness, even eagerness, to look silly, sordid, and ridiculous is key to its greatness. Coogler and his collaborators take massive risks that all play out beautifully.

I’m not proud that the only Coogler-Jordan collaboration I’ve seen was Black Panther. Jordan’s turn as Killmonger is perhaps the single greatest performance in the MCU.

With Black Panther, Coogler elevated the superhero movie to the level of high art that is defiant in its unapologetic blackness. He accomplishes a similar feat here.

Coogler has carved out a place in film and pop culture for stories about Black life, full of beautiful, brilliant, gorgeously attired African-American characters who possess power, agency, and control over their lives and their world.

I might feel ambivalent about the concept of Elevated Horror, but I appreciate fright flicks like this that set out to do more than just scare audiences. Sinners is visceral yet cerebral, a feast for the senses as well as a treat for the mind.

Five stars out of five

I guarantee the only focus groups that would find that dance sequence silly are ones with no black folks. Because that’s who it was meant to resonate with (and it does).

This sounds amazing. Can't wait to see it. Ryan Coogler is a magnificent filmmaker. The second Black Panther movie was (to me) a moving portrayal of living through tragedy and the resulting guilt and grief. An elevated Marvel movie, if you will.