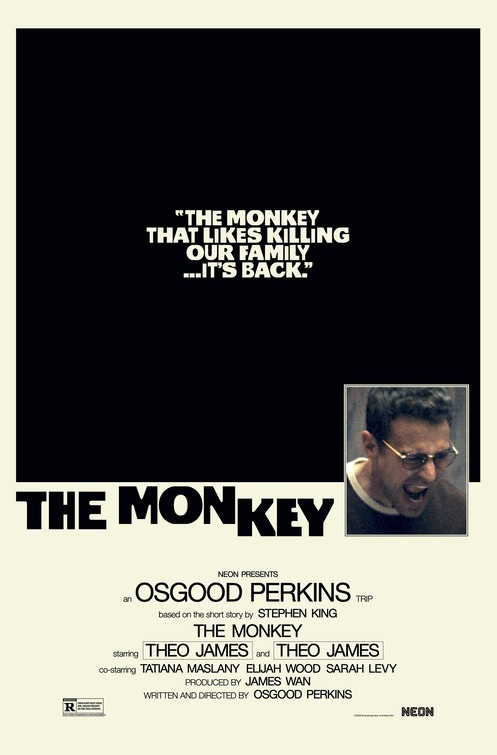

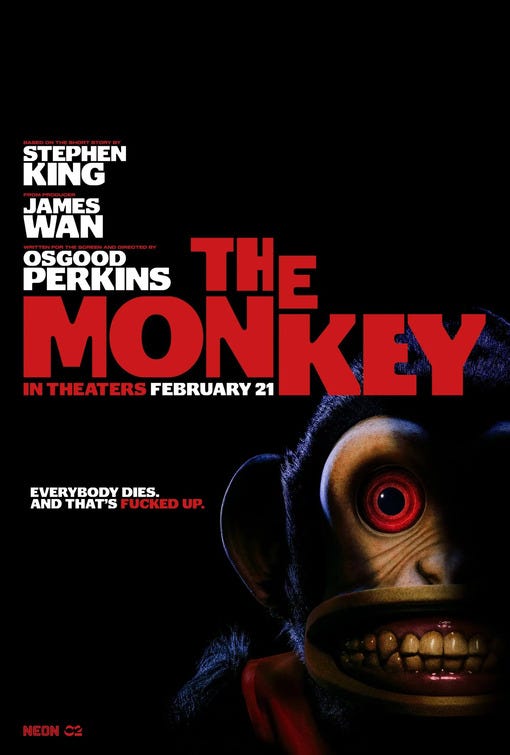

Osgood Perkins' Adaptation of Stephen King's The Monkey is Wonderfully Warped and Delightfully Deranged

Perkins' follow up to Longlegs is Osgood to the point of being Osgreat!

While researching my Stephen King project, I learned that John Carpenter wanted to adapt Firestarter but lost out on that gig due to The Thing’s box office failure and production delays. Carpenter got to direct Christine instead as a consolation prize.

Christine was Carpenter’s second choice. That helps explain why neither Carpenter nor King seems particularly happy with the 1983 horror movie about a killer car that transforms a nerd into a scary greaser.

In King’s book, we learn that the titular automotive mass murderer has an insatiable desire to kill because the spirit of previous owner Roland D. LeBay possesses her.

In Carpenter’s adaptation, however, the titular automobile suffers its first casualty while still on the assembly line. It’s evil from the very beginning. The screenplay suggests that its sinister mojo is connected to a ghoulish former owner, but it never conclusively establishes that Christine kills because LeBay possesses it.

I mention this because The Monkey, Osgood Perkins's adaptation of King’s 1980 short story of the same name, takes a similar approach but yields much more satisfying results.

Christine’s unwillingness to disclose the nature and origin of its supernatural menace irritated me, whereas I respected Perkins’ decision to present the titular terror as an enigmatic manifestation of the universe’s unrelenting sadism.

The Monkey opens in a state of hysteria. We begin with a prologue where Capt. Petey Shelburn, a blood-stained deadbeat dad played by Adam Scott, visits a pawn shop in a desperate bid to get rid of a tacky children’s toy that has been tormenting him.

The understandably terrified and confused pilot can’t explain why the simian musician is evil or exactly how he came to be a Satanic force. He just knows that the ominous little bastard will kill him and/or people close to him if the monkey starts to play his drum.

The Monkey is a pitch-black comedy of brutality and amorality that gleans big laughs from the myriad colorful ways human bodies can be destroyed. There’s a lot of corpse-based comedy in The Monkey because it is filled with corpses who died the opposite of a natural death. It’s nothing but freak deaths for these cursed souls, the freakier and deadlier, the better.

In that respect, it reminded me of Pulp Fiction and Final Destination. The Monkey suggests an arthouse take on the popular freak death-based horror franchise or a version of Pulp Fiction in which moralism is replaced by nihilism.

In 1999, the pilot’s identical twin sons Hal and Bill (Christian Convery, in a dual role) discover the malevolent monkey in their late father’s belongings. He didn’t leave them with much, and what little he did qualifies as pure, deathless evil. That’s worse than nothing. Like a lot of shitty dads, the boys’ father leaves behind a legacy of failure, abandonment and death.

The brothers wind up the mischievous music-maker, leading indirectly to the gruesome decapitation of their babysitter.

Hal, the sensitive, responsible twin, tries to use the monkey’s inexplicable powers of destruction to kill his belligerent bully of a brother. In a development out of W.W. Jacobs’ classic short story “The Monkey’s Paw,” the monkey kills off a member of Hal’s immediate family. Unfortunately for Hal, the boys’ sharp-witted, sardonic mother, Lois (Tatiana Maslany), dies instead of the intended target.

Hal is filled with guilt. He feels responsible for his mother’s brutal death. His life is filled with trauma and grief.

He grows up to be a troubled soul with a complicated relationship with his son, Petey.

Hal only sees his son once a year to prevent him from succumbing to the monkey’s malevolent mojo, but he does not tell his ex-wife the reason for his infrequent visits because he does not want to be seen as mad.

Bill was already something of a sociopath even before the mysterious deaths of his babysitter and mother left him in the questionable care of their swinger uncle Chip (Osgood Perkins, who has his dad’s face and Elvis’ sideburns) and aunt Ida (Sarah Levy).

In The Monkey, agonizing freak deaths are the punchline of the cosmic joke of life.

Theo James plays the adult versions of Hal and Bill. It’s a remarkable dual performance that makes an absurd premise tantalizingly real. My wife was so impressed that she did not realize that the same actor played the brothers.

After decades of absence, Bill lurches back into his twin brother’s life to warn him that the monkey will soon start banging on its drum, and the corpses will begin piling up all over again.

An air of ominous inevitability hangs over The Monkey. As Lois tells her children, the one thing that has united human beings since the beginning of time is that everyone dies. It’s the great common denominator.

In The Monkey, there is no such thing as a natural death. Death is inherently unnatural. No one dies from old age. Death comes at its characters from every angle. It’s relentless, cruel and unforgiving. There is no logic to it.

One moment a character has their whole life ahead of them; the next they’re a pile of muscles, bones and pink goo.

The Monkey has an enormous strength in the monkey. It’s an unusual horror movie villain in that it doesn’t really do anything. It doesn’t talk. We never see it moving of its own accord. Like Nicolas Cage in Longlegs, Perkins’ previous film, he does not directly participate in murders.

The Monkey may be an inanimate object, but that doesn’t make him any less terrifying. The Monkey exploits the innate creepiness of old, abandoned toys. The antagonist is pure nightmare fuel; the juxtaposition of the drummer’s creepily realistic teeth and mouth and the dead doll’s eyes never stops being unnerving.

This was a two-movie weekend for me. On Saturday night, I saw The Monkey with my wife; last night, I saw Paddington in Peru with my son. I enjoyed both movies tremendously.

Paddington in Peru and The Monkey aren’t just different; they’re damn near antithetical, but they’re both very much worth seeing. Paddington in Peru is all sweetness and light, while The Monkey luxuriates in infinite darkness.

Four stars out of Five

I honestly didn't mind the "Christine" movie's take on the titular car being, shall we say, bad to the bone. It certainly wasn't out of place in a Stephen King milieu, where people, creatures, or objects are often described as Just Plain Evil. My only problem with the movie was the lack of certain set-pieces from the book, although that may have been driven by budget rather than any deliberate choice.

It sounds like they went in the completely opposite direction with "The Monkey"; the original story was fairly stripped-down and had a reasonably low body-count. The chills came from the dread of not knowing when or where the Monkey would turn up after any attempt to get rid of it, and of the protagonist's desperation to protect his son. (I sure as hell will see the Oz Perkins version, though.)

Rock n' Roll Martian - from another toy monkey-related film Merlin's Shop of Mystical Wonders (and Nightcrawlers) ;)