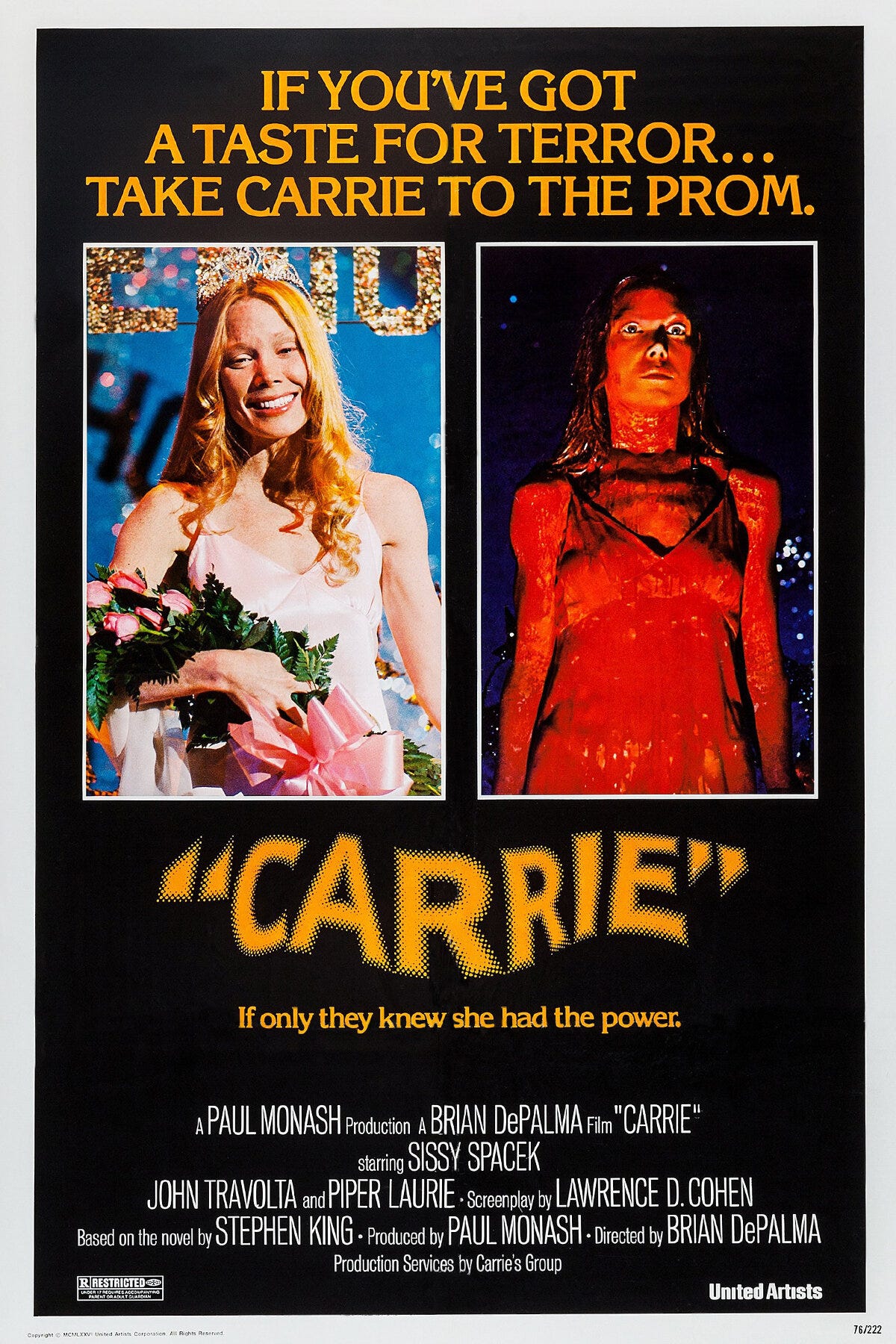

My Exploration of Stephen King's Films Begins in a Big Way With Brian DePalma's Iconic 1976 Adaptation of Carrie

King's cinematic debut is a bloody good time!

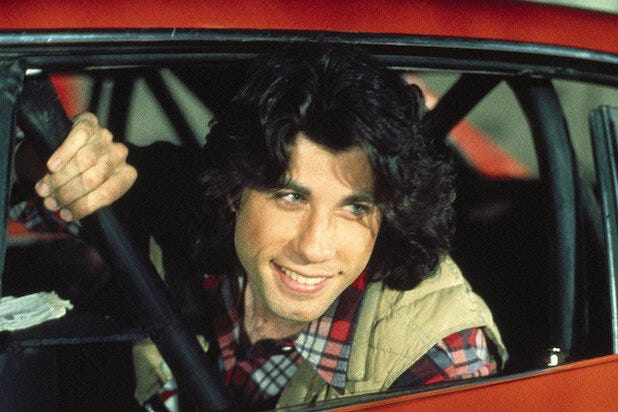

Before he was Vincent Vega or the Fanatic, John Travolta was a pouty-lipped high school hunk in 1976’s Carrie, a classic teen movie that cost but a pittance but broke wide and made a fortune thanks to its riveting and iconic take on the joys and horror of teen life and copious nudity.

Though Travolta had appeared briefly in the poorly received 1975 horror film The Devil’s Rain, his film career began with a scene-stealing turn as a teenage bully in 1976’s Carrie. The same is true of Stephen King, whose career as a prolific source of cinematic fodder began, suspiciously, with the one-two punch of 1976’s Carrie and 1980’s The Shining, two of the scariest, most important and acclaimed horror movies of all time. He really came roaring out of the gate, cinematically.

In Carrie, Travolta’s character is defined by his incandescent sensuality. Travolta’s Billy Nolan uses his handsomeness for evil. Billy uses his crude understanding of pulleys and pig’s blood to help turn a prom into a pyrotechnic nightmare, a telekinetic bloodbath with the body count of a small war, as well as one VERY pissed young lady who gets revenge on a world that treated her with unrelenting cruelty in the biggest, boldest, bloodiest possible fashion.

In Carrie, Travolta receives a leering introduction that posits him not just as an unusually handsome young man with a healthy libido but rather as a stud to be leered at. Travolta’s Billy is fully clothed throughout Carrie, but that does not keep director Brian DePalma’s camera from ogling him. Carrie borders on soft-core porn in its gauzy, vaseline-smeared, slow-motion depiction of the dewy, frequently unclothed world of high school girls as sexy as they are cruel, but if DePalma is not anything close to an equal opportunity voyeur, he sexualizes Travolta and William Katt as the prom king just as intensely as he does the beautiful naked young women in his cast.

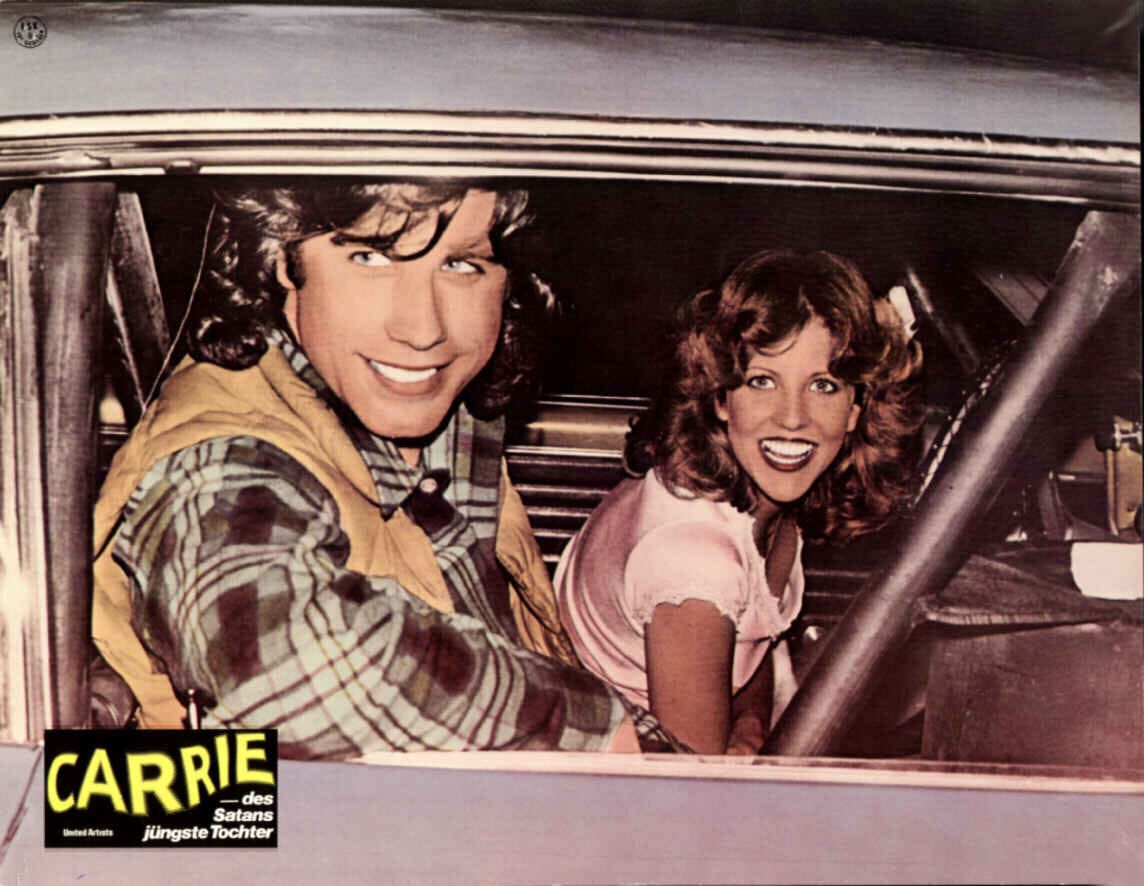

Billy Nolan is introduced riding around in a car with girlfriend Chris Hargensen, who Nancy Allen plays as the meanest of mean girls, a popular girl who isn’t just nasty, she’s a fucking sociopath. In Carrie, as in life, being sexy and being a sociopath go hand in hand; look good enough, and people will let you get away with anything, with the notable exception of vengeance-crazed telekinetic outsiders.

The whole world wants to fuck Billy and Chris or to hang out with them on the chance that it will increase their chances of getting laid.

With a shit-eating grin on his gorgeous punim, Billy is driving with his girlfriend in the passenger’s seat, Martha & the Vandella’s “Heat Wave” blaring on the car radio. Even the soundtrack seems to be lusting after these kids. First up a pair of dumbass bros try to get Billy to join them in the pursuit of some “hard stuff” but Billy leers at his girlfriend’s breasts and decides that he has better things to do but happily accepts the beer they toss into his car.

Next, an entire car-full of beautiful young women holler their appreciation of Billy’s precocious beauty, either oblivious to his girlfriend’s presence or unconcerned about any lingering romantic or sexual attachments the beautiful young man might have.

Then the police pull up to the side of Billy’s car, but even they let him pass when he spills his beer on his passenger; she calls him “Stupid shit,” an insult she tosses his way with such frequency that it threatens to become a pet name. Billy and Chris have a toxic relationship: she continually calls him a stupid shit for behaving like a stupid shit, and he continually smacks her in retaliation.

Every time Billy and Chris have sex, it’s undoubtedly hate sex. That’s who they are. They are bad people who bring out the worst in each other. Then Chris goes from icy cold to white hot and begins sucking sensually on one of Billy’s fingers before going down on him.

Billy unzips his pants before Chris reveals the real purpose of the automotive seduction. “Oh Billy, I hate Carrie White,” she seethes pre-blowjob, to which Billy can only manage a simultaneously perplexed and enraged, “Who?”

Travolta plays the moment perfectly; he is a callow creature of pure need with a distressingly sadomasochistic relationship with a girlfriend he hates and who hates him. All that matters in the moment is satiating his single-minded lust. Chris upends the erotic intensity of the moment by bringing mean-girl high school politics into the equation at the worst possible time.

The scene is funny, dark, and bracing but also sets up the climax. Chris is filled with incoherent rage towards Carrie for getting her into trouble with gym teacher Miss Collins (Betty Buckley), so she convinces her asshole boyfriend to play a prank on the poor girl, which will lead to their violent deaths.

In Carrie, sex and violence are inextricably intertwined. So it’s fitting that a strategic blow job plays a crucial role in getting an awful young man to do something unspeakably sadistic, even by high school standards.

Carrie opens on a note of sensuality so over the top and pervy, even by DePalma standards, as to be parodic. We open on a very slow shot of a girl’s locker room full of beauties in various states of undress. We arrive, finally, at the naked body of our heroine/anti-hero/villain Carrie White (Sissy Spacek), as she caresses her nubile naked form in a way that would lead to an orgasmic masturbation scene in a different, more “European” kind of film.

In Carrie, however, the scene famously climaxes with Carrie, whose psychotically Christian mother has gone out of her way to keep her ignorant and afraid about her body and everything else, feeling and seeing menstrual blood leave her body for the first time. A sensual paradise for people who like to ogle naked young women morphs instantly into high school hell as the mean girls, led by Chris, torment their awkward peer, taking brutal delight in her helplessness and naivety.

Carrie’s life is even worse at home. Carrie’s religious freak mother, Margaret (Piper Laurie in a scarily committed, Oscar-nominated performance), terrorizes her in the name of Christ, forcing her into a prayer closet whose defining feature is a representation of Jesus on the cross because she wants her traumatized daughter to experience bad dreams so shattering and intense that they make her never want to wake up.

Sue Snell (Amy Irving), the rare popular girl with a conscience, convinces her boyfriend Tommy Ross (William Katt) to ask Carrie to the prom as penance for being part of the gaggle of cruel girls who mocked Carrie’s distraught, overwhelmed response to her first period.

Carrie occasionally appears to be on the verge of devolving into a She’s All That-style romantic comedy about a handsome jock who asks an awkward, unpopular, but stunning outcast to the prom under false pretenses but ends up falling for her all the same.

There’s a fascinating element of ambiguity to Katt’s performance. At first, it is achingly apparent that he only asks Carrie to go to the prom because his girlfriend asked him to do so. He is not very good at pretending otherwise, or pretending at all.

But he genuinely seems to warm to Carrie. The pity date to the prom threatens to become more authentic. The hint of kindness and mercy makes the cruelty and violence that follow more powerful. The world of high school is unfathomably but realistically cruel in Carrie, just as in the real world.

So, while Sue and Tommy go out of their way to make the world a little kinder to Carrie, Chris and Billy have a surprise of their own. They shamelessly rig the prom king election system, an act of pure evil in its own right, to ensure that Tommy and Carrie win but that Carrie has a bucket of pig’s blood dropped on her head during her cruel, mocking coronation.

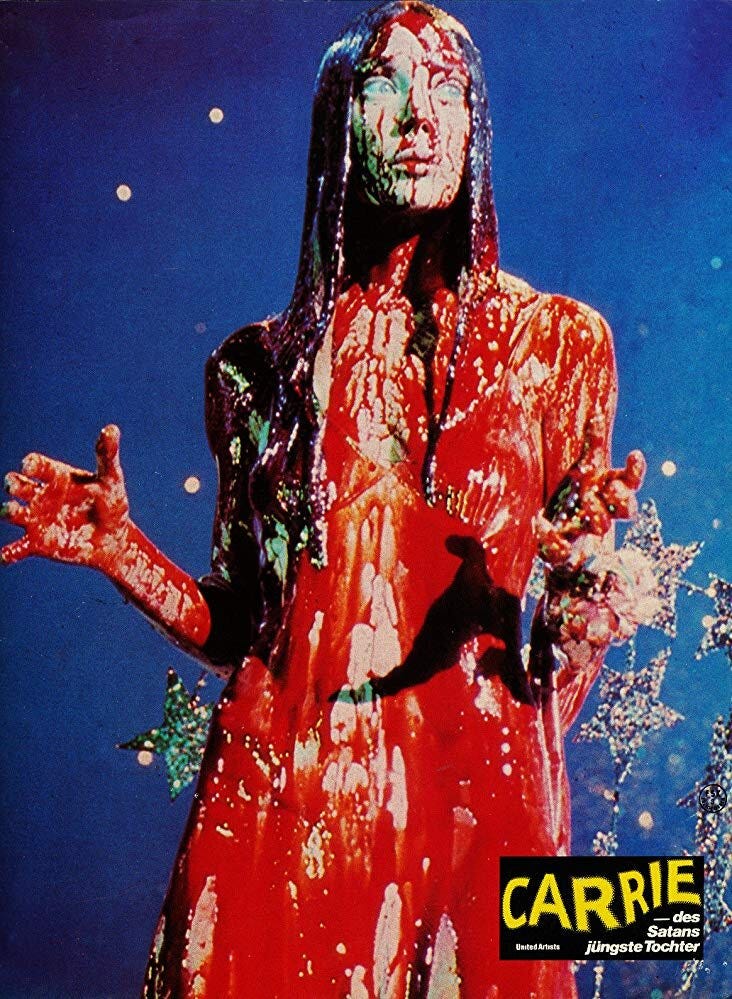

Carrie’s ostensible moment of triumph becomes one of ultimate humiliation. The psychic powers she has struggled to keep at bay all film long are unleashed in a furious, fiery symphony of destruction. Carrie is no longer a shy, scared little girl but an angry, apocalyptic force.

The look of anxiety, fear, and vulnerability Carrie sported throughout the film is replaced by the steely, purposeful gaze of someone who knows exactly what they must do and how. There is no more uncertainty or doubt. All that is left is the will to destroy a world that destroyed her fragile spirit, turning her into a monster.

The horrors of Carrie are rooted at once in a very Stephen King combination of the spooky and supernatural and the relatable and banal. Carrie is fundamentally about the sadism and brutality of high school conformity as well as the ugliness and brutality of religion when used to oppress and torment rather than liberate and save.

Carrie is a villain, but she’s just as unmistakably a victim. In Carrie, DePalma created a female version of Psycho with a similarly heartbreaking, multi-dimensional killer at its core who fascinatingly blurs the line between hero and villain, victim and victimizer, monster and monstrously relatable flesh and blood human being.

Carrie brought Stephen King to the big screen in a big way. An even bigger, even more iconic adaptation would follow in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of The Shining. Carrie set the bar for King adaptations so impossibly high that only Kubrick, arguably the greatest filmmaker our country has ever produced, could clear it.

My first horror movie and it was fantastic. I still watch it every once in a while. Sissy Spacek was outstanding in her role.

That intro scene of Carrie in the shower seems all kinds of wrong today, but I can see how it would have worked as a bait-and-switch on 1974 audiences who were there for a lurid exploitation film, only to be collectively c-blocked by a brutal bullying scene.

(And FWIW, that scene is pretty much note-for-note from the book.)