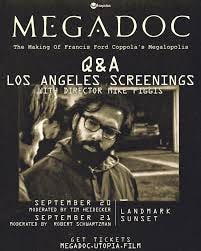

Mike Figgis' Megadoc is a Riveting Exploration of the Madness and Massive Miscalculation of Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis

You know a movie shoot is fucked up when Trump worshipper Jon Voight is often the most reasonable and relatable figure onscreen.

I am nearly finished with The Fractured Mirror, my mammoth upcoming book where I write about every narrative American movie about filmmaking and a fascinating cross-section of documentaries on the subject.

In fact, Megadoc will be the final entry written for the original version of the book. I’ve been driving myself crazy writing The Fractured Mirror. It has required a Fitzcaraldo/Apocalypse Now level of obsession and work.

The task of writing The Fractured Mirror got bigger and more amorphous as I searched endlessly for obscure movies that fit the criteria for the book. I never stopped looking for more movies about making movies. The problem is that if you never stop, then you never finish, and you end up spending three years writing something you envisioned completing in half that time.

When I saw that Timecode director Mike Figgis had made a behind-the-scenes documentary about Megalopolis, I knew that I had to see it and write about it. I love documentaries about famously disastrous film productions. I leaned heavily on that rich subgenre in The Fractured Mirror because, as Figgis himself acknowledges late in the film, the great documentaries about filmmaking are almost invariably about disasters.

One big exception is Hearts of Darkness, the legendary documentary about the making of Apocalypse Now, a crazy dream Francis Ford Coppola realized against incredible odds. Hearts of Darkness was one of the all-time great moviemaking documentaries, just as Apocalypse Now is revered as one of the greatest, most beloved, and influential American films of all time.

I suffered through Megalopolis twice, first for this newsletter and then for My World of Flops. That means that I’ve now spent five hours in this world. I hated every minute.

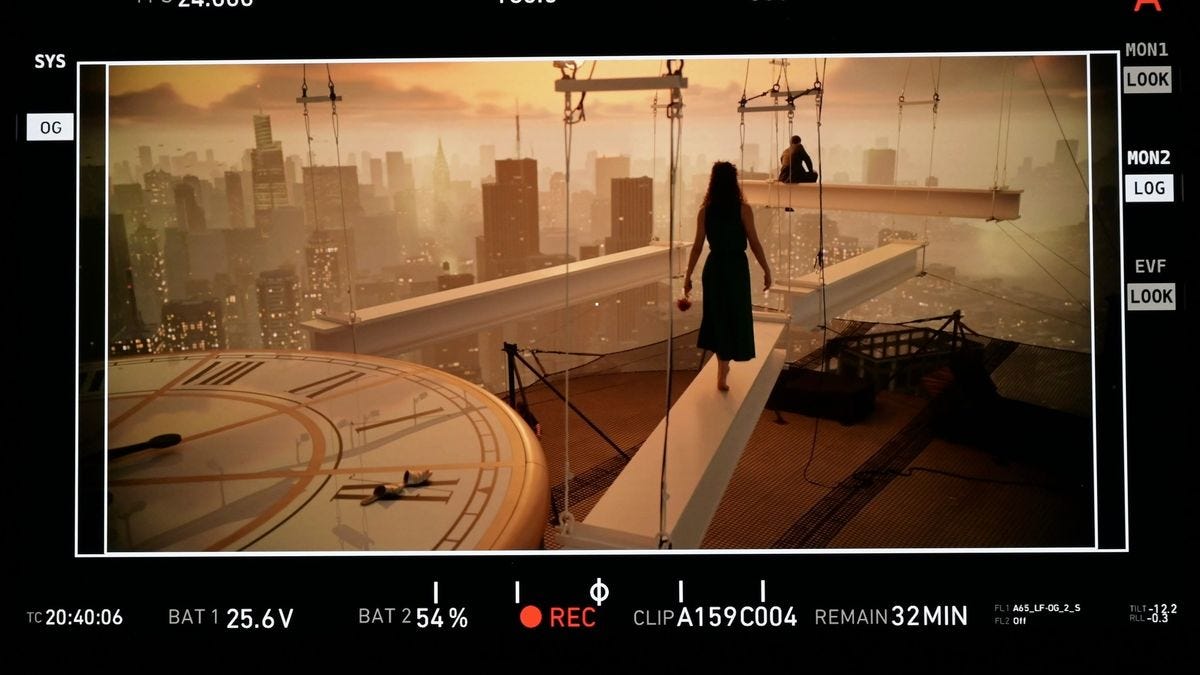

Megalopolis is the kind of movie I generally love: original, audacious, ambitious, and a profoundly personal vision from a legendary filmmaker with a burning need to be relevant and say something meaningful about our crazy-making world.

The same burning intensity that created Apocalypse Now led eventually to Megalopolis. In both cases, Coppola defied the one sacrosanct rule of the film industry: never invest your own money, or you’ll lose it.

An exception can be found in George Lucas, Coppola’s good friend and frequent collaborator, and a talking head here whose dorky practicality is much more bearable than Coppola’s flamboyant megalomania. The Star Wars movies Lucas financed were just a tiny bit more commercial than what Coppola was attempting with Megalopolis.

Granted, Coppola rolled the dice and came up a big winner with Apocalypse Now. Coppola took one of the great all-time Ls with Megalopolis, a bewilderingly pretentious, vulgar Randian meditation on modern-day America through an ancient Roman prism.

Like many of the filmmakers that I write about in The Fractured Mirror, real and imaginary, documentary or narrative, Coppola represents an unusually pure, real-life example of a movie fixture: the maverick filmmaker who risks it all on a crazy dream.

Coppola sold off much of his very successful wine company so that he could invest one hundred and twenty million dollars into a monstrosity that grossed zero dollars at the box office.

I don’t even know how that’s possible. I saw it twice myself, and since it wasn’t playing at one of my beloved Regal theaters, I had to pony up eighteen bucks per ticket.

I’m a little surprised that Megadoc is hitting theaters, considering the $ 120 million, star-studded Francis Ford Coppola would-be comeback movie it chronicles with humor and horror was barely released and spectacularly unsuccessful in every way.

I had to travel twenty miles each way to see the documentary’s only afternoon showing. Once transportation is factored in, it cost me sixty-five dollars to see Megadoc. Coppola lost most of his fortune making Megalopolis, so I got off easy.

Watching Megalopolis, I found myself thinking, Why? Why would Francis Ford Coppola make this movie at this stage in his life? How? How could this travesty have happened? How could the man who made Godfather, Godfather Part II, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, and, most of all, Jack, make something so unique yet unwatchable? What was he thinking? What was he smoking?

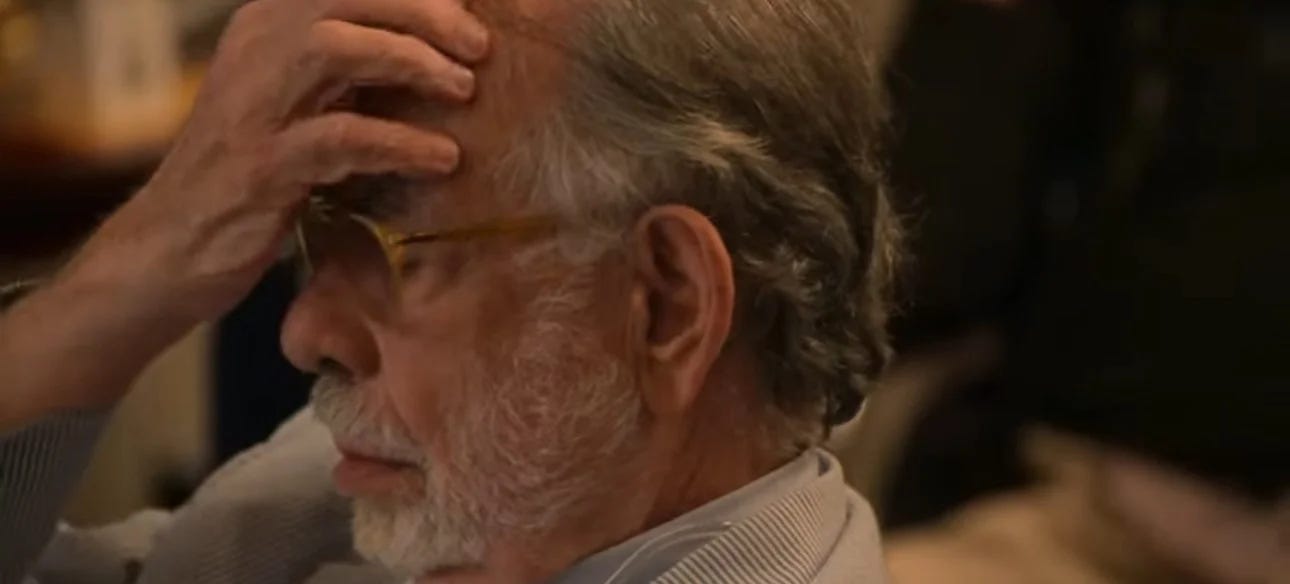

Contemporary journalistic accounts can answer that final question at least. Apparently, he was smoking some of that wacky tobacky. He was blazing fat ones in his trailer. By all indications, he was not a groovy, fun chill stoner to kick it with. The Francis Ford Coppola that emerges here is kind of a miserable son of a bitch. He’s angry and unhappy, as his costly dream slips away from him before his eyes.

With Megalopolis, Coppola tried to outdo himself, to create his greatest, craziest, and most ambitious masterpiece. Instead, he mostly ended up arguing with Shia LaBeouf, who gives the Godfather director Marlon Brando levels of agitation and irritation without Brando levels of talent.

Megadoc begins on a fragile note of optimism, hope, and excitement. One of our greatest and most influential filmmakers was returning to the big screen after an extended absence to make a profoundly personal labor of love that had been rattling around his cerebellum for forty years.

When Coppola tells Figgis that Megalopolis will be bigger than Apocalypse Now, I’m reminded of the moments in American Dreamer, the documentary about The Last Movie, when Dennis Hopper confidently asserts that his follow-up to Easy Rider will be more successful than the iconic biker movie that helped kick off the New Hollywood renaissance.

I'm not sure whether Coppola believes his own bluster, but he could not be more wrong, unless he is referring to Megalopolis being a bigger disaster and a bigger embarrassment than his surrealistic take on Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

In its embryonic stage, Megalopolis could be anything. It could be Apocalypse Now, or it could be One From the Heart. Coppola could not have envisioned that he’d make a flaming fiasco so historically awful that it makes a flop like One From the Heart look like a Godfather-like triumph by comparison.

Coppola, the cast, and the crew’s enthusiasm cannot help but affect Figgis. He’s excited about making a movie about one of his creative heroes attempting the impossible as an octogenarian operating outside the studio system.

The five-time Academy Award winner encourages a spirit of playfulness and experimentation. The ambitious old man wants to create a child-like sense of wonder and possibility among actors for whom appearing in a 120 million dollar Francis Ford Coppola is a dream come true that eventually devolves into a waking nightmare.

Coppola is a charismatic cult leader who infects his cast and crew with his idealism, ambition, and intensity. From the very beginning, he is pretentious and more than a little insane.

What genius isn’t touched with madness? Coppola has reasonable ambitions. All he wants to do with Megalopolis is heal the world and reinvent cinema. With those modest expectations, it’s surprising he failed.

The famously press-shy Adam Driver limited his participation in Megadoc to a single sit-down interview despite his admiration for Figgis, an ambitious and experimental filmmaker in his own right.

Into this void leaps Shia LeBeouf, who expresses amazement that he wasn’t replaced after he was cancelled for physically and sexually abusing ex-girlfriend FKA Twigs.

Coppola’s early talk about improvisation and play deludes LeBeouf into thinking that the legendary filmmaker wants to be challenged and provoked. He does not.

Throughout Megadoc, Coppola’s body language and facial expressions toward LeBeouf silently scream, “Shut the fuck up and do what I tell you to. I made The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. You made movies about robots that turn into cars. Respect my authority.”

Coppola’s words aren’t much friendlier. Figgis discusses going into the project without knowing what kind of movie he would ultimately make. I do not believe that he set out to direct a negative movie that portrayed Coppola in a very dark light.

Surprisingly, or unsurprisingly, Figgis ended up making a movie about a toxic and tension-filled set dominated by the friction between LeBeouf and Coppola, whose massive egos and pretensions conflict early and often.

LeBeouf worries that he'll be fired and replaced. That doesn’t keep him from challenging Coppola in a way that makes him, and the audience, want to murder him. I’m not sure any jury would convict him if he had.

The filming of Megalopolis was so surreal and tense that Jon Voight, who is better known these days for his worship of Donald Trump than his acting, is the most normal and relatable figure in many of his scenes.

Coppola begins the film as a passionate idealist eager to risk it all for a vision so vast and complicated that even he doesn’t seem to grasp it in its entirety.

Coppola grows increasingly bitter and unhappy when the cast and crew, understandably eager to avoid being yelled at or singled out for criticism by someone they seem to like and respect less every day, struggle to give Coppola what he wants.

The psychological cost of having to deal with a depressed tyrant who doesn’t know what he wants, but knows that he’s not getting it, can be measured by the forced smiles of collaborators who are exhausted and confused and all too aware that they’re devoting their time and energy to an all-time disaster rather than a contemporary Apocalypse Now.

Coppola begins the film as an inspirational figure, a giant of New Hollywood trying to make a major statement in a world that he does not seem to understand or like. He ends it as a cautionary warning of the dangers of having too much: too much money, too much freedom, too much cast and crew, and too much ambition without enough self-discipline or self-control.

Megalopolis, unsurprisingly, would make for a terrific double feature with Hearts of Darkness. They're fascinating cinematic bookends. One chronicles the making of an all-time classic. The other documents the creation of a disaster of historic proportions, but they’re both essential explorations of movie-making at its craziest and most intense.

4.25 stars out of 5

Hey, it's me, yeah, the guy who wrote the above article and ALL of the pieces on this site. I'm writing to you briefly about becoming a paid subscriber. The older you get, the harder it becomes to make a living as a freelance writer. I've been doing this professionally since 1997, so it is exceedingly difficult to make even a modest living as a full-time freelancer in a brutal economic climate like this.

That's why I am supremely grateful for paid subscribers, particularly people who choose the year-long option, which costs just 50 dollars but lasts 365 days. 366 on leap years! I was making steady progress in terms of growing the site until about two months ago, when everything started spinning in the wrong direction so I very much appreciate every kind soul who decides that five dollars a month is a reasonable price to pay for three exclusive Joy of Positivity picks a week, the right to vote in polls to determine what I have to watch every weekend, and, last but not least, support a veteran writer and author who has caught some tough breaks over the years.

If you become a paid subscriber, the money instantly goes into my Stripe account. That gives me a big boost emotionally and financially. It's wonderful validation at a reasonable price.

If you cannot afford a paid subscription, there are other ways to help, such as restacking or recommending this newsletter.

Thanks for reading. You have countless options on Substack alone, so it means a great deal to me that you're here.

This review reminds me of Overnight, the doc about Troy Duffy and the making of The Boondock Saints. In both cases the documtary filmmaker starts out in the director's corner only to pushed away by ego and general jackassory.

I have not seen Megalopolis, but I believe the parallels are to ancient Rome, not Greece.