In the first Silly-Show Biz Book Club Piece Here I Take a Deep Dive Into the Shallow Waters of Matthew Perry's Friends, Lovers, and the Big, Terrible Thing

I'm in this book! A lot! It's weird!

Welcome, friends, to the first entry in the third incarnation of Silly Little Show-Biz Book Club. It’s a column that began fifteen years ago during my time as the head writer of The A.V Club.

I moved it to Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place in 2017. Now it’s part of the new, revamped, hopefully more successful Nathan Rabin’s Bad Ideas.

I started the column because I love books about entertainment written by authors who embody an archetype that I find endlessly fascinating: crazed narcissists devoid of self-consciousness who have no idea that the world sees them much differently than how they see themselves.

I’ve written about memoirs by the rich and famous, as well as books by opportunistic hangers-on: groupies, bodyguards, personal assistants, children, wives, girlfriends, drummers, and the like.

One particularly memorable entry in the column found me writing about This Is It, a memoir by Conrad Murray, the ghoul who killed Michael Jackson. He’s a narcissist apoplectic that the world inexplicably seemed more interested in Michael Jackson, who for years was the most famous and successful entertainer in the world, rather than him, a quack known only for the central role he played in Michael Jackson’s death.

Murray was better educated than any author I’ve covered in the column, but he was every bit as sleazy, self-aggrandizing, and unethical.

I’ve written about some great books for this column, like Sammy Davis Jr.’s Yes I Can (seriously! It’s so much more than a throwaway gag on The Simpsons) and some wonderfully terrible books and books that are straight-up unreadable garbage.

If someone self-publishes a poorly written, badly edited manifesto because they have a weird grudge against someone much more famous than them, I want to read it. I am irrevocably attracted to the obscure, the bizarre, and the disreputable.

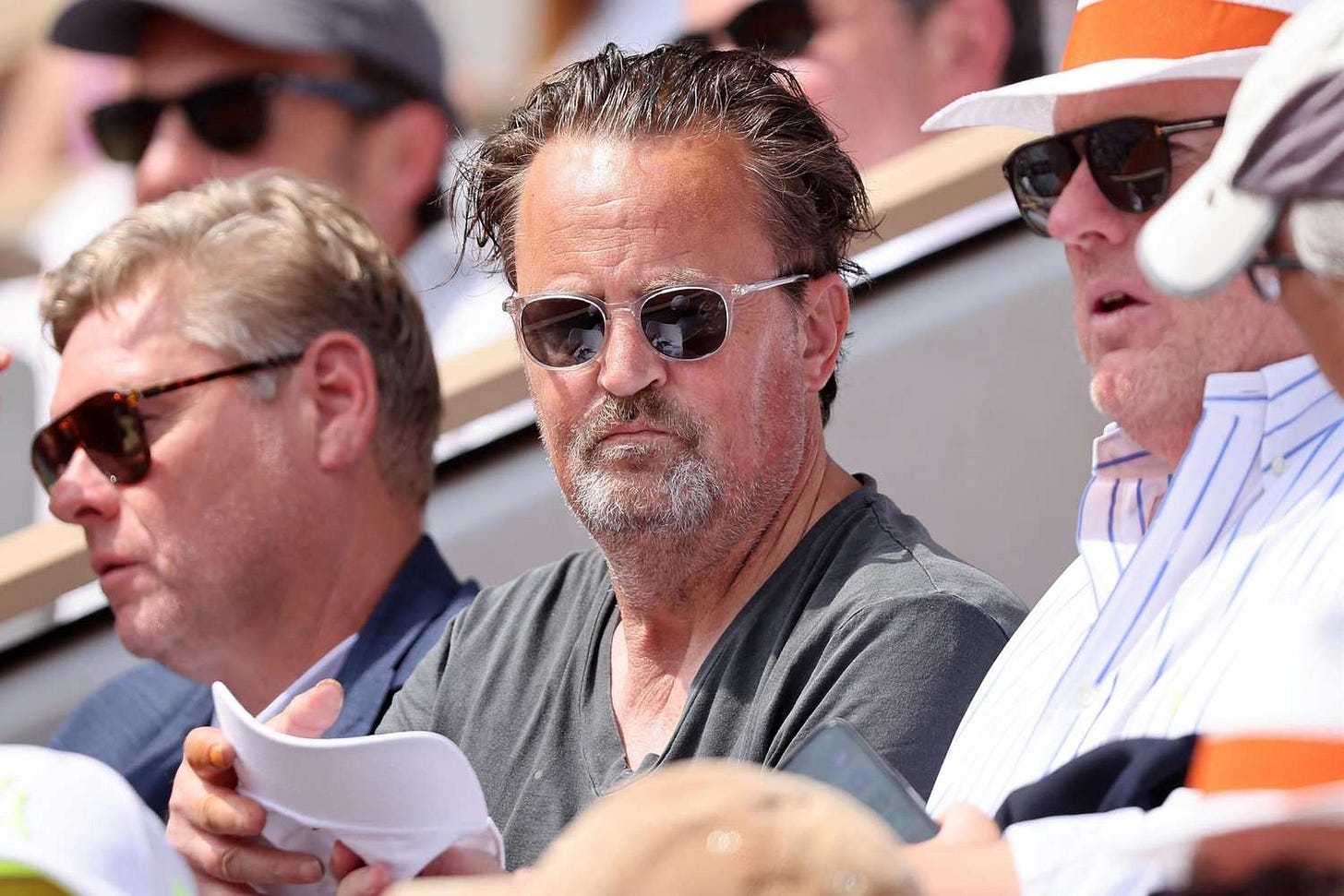

So I will begin this new incarnation of an old column with something utterly out of character: a much talked about, controversial best-seller from an actor famous for a show that pretty much defines the mainstream: Matthew Perry’s Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing.

In the 2003 Stephen King adaptation Dreamcatcher, Morgan Freeman plays a military man who infamously delivers a monologue paying tribute to everyday Americans who “drive Chevrolets, shop at Wal-Mart, (and) never miss an episode of Friends.”

In his memoir, Perry argues that he would happily trade all the money, fame, and beautiful women for a life as a nobody who drove a Chevrolet, shopped at Wal-Mart, and never missed an episode of Friends but did not spend decades wrestling a fierce battle with alcoholism and drug abuse.

As a rule, I do not write about popular topics people care about. Yet, despite its popularity, success, and respectability, I felt a strange connection with the book.

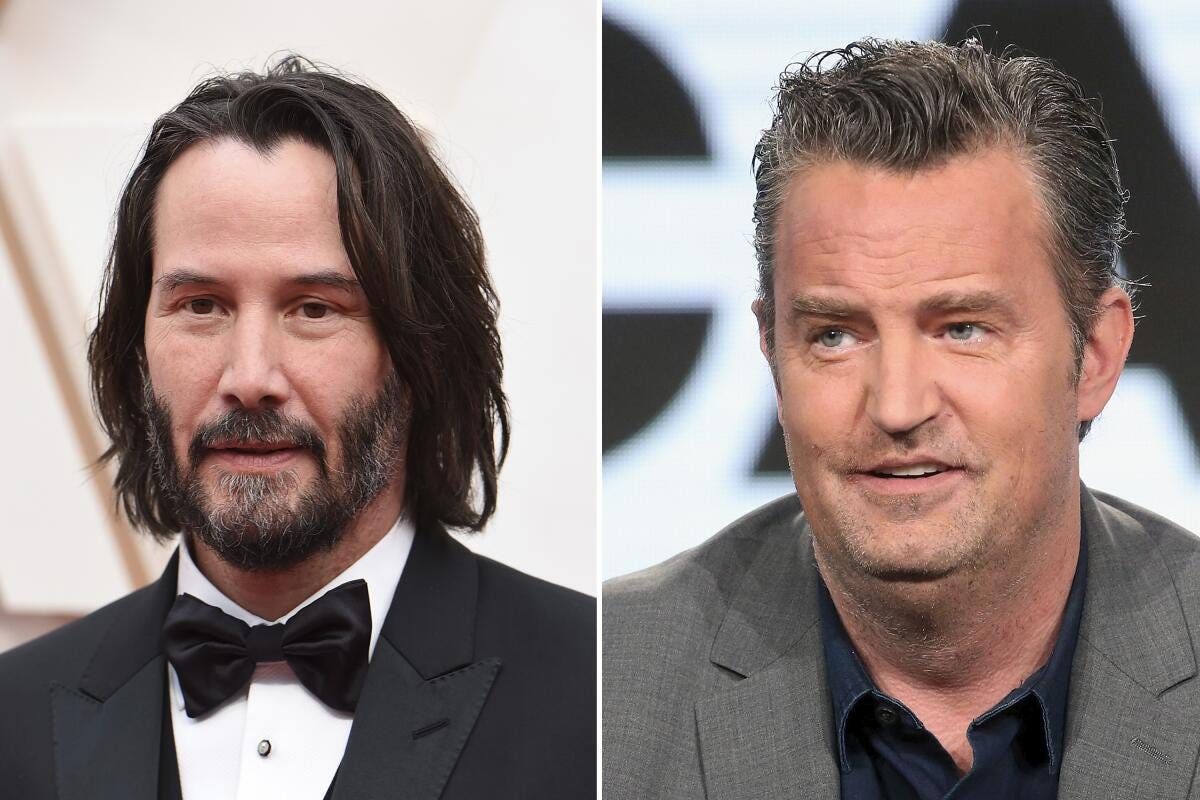

That’s partially because, for months, I had a bad taste running gag at Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place lampooning the infamous part of Perry’s memoir where he expresses his sadness and grief that his A Night in the Life of Jimmy Reardon costar River Phoenix and his Almost Heroes pal Chris Farley both died young of drug overdoses while Keanu Reeves tragically continues to live.

These passages from Perry’s bestseller proved so controversial that they were deleted from later printings. Perry apologized for his ill-conceived and poorly received joke. They weren’t in the paperback copy that I read. Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing is better for their absence.

Perry’s memoir contains jokes, which can be deadly in a memoir.

I should know! A while back, I began to re-read my 2009 memoir, The Big Rewind and was horrified by my need to make my formative traumas more palatable with humor.

I made jokes in my literary debut for the same reason Perry does: I was painfully insecure, and worried readers would reject me and my story as a stone-cold bummer unless I made them laugh.

I didn’t realize at the time that I was sabotaging myself by doing shtick instead of allowing myself and my story to be sad and giving my pain space to breathe. If I could go back, I’d cut many of the jokes from The Big Rewind. I hopefully reached a point where I realized that I didn’t need to be a clown to keep people engaged.

Ironically, that point came when I was writing You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me, a memoir, travel book, and amateur exercise in pop culture sociology about the Wicked Clowns, Insane Clown Posse, and Phish, and their fanbases.

Perry apologized for joking about the death of a beloved actor and cut the offending lines from his book. I also apologized for joking about the death of a beloved actor after Perry died.

I see now that I was doing exactly what I was making fun of Perry for. I could see both the hypocrisy and ugliness of making a dumb running gag out of something that was legitimately tragic and had a surprisingly vast cultural impact in part because Perry lost his fierce, decades-long battle with drug addiction shortly after publishing a best-selling memoir about winning his war with substance abuse.

I made a mistake. That’s what I do. I must forgive myself for my intense failability, or I will go insane.

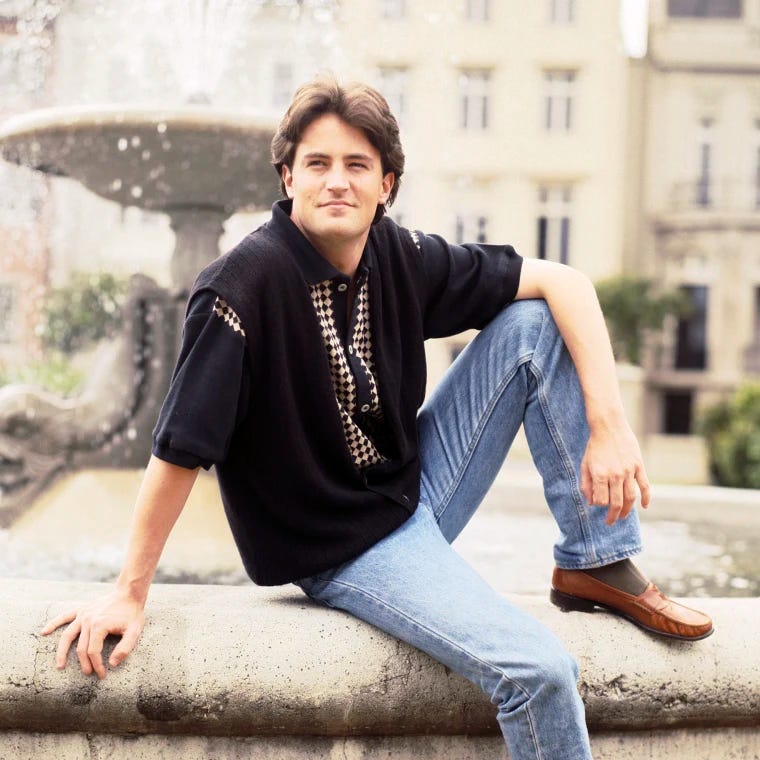

Perry was self-aware enough to know that, like Chandler Bing, the character he played for a blockbuster decade on Friends, he can’t handle awkwardness and feels the need to fill silences with humor.

However, this does not prevent him from overcompensating for the grimness of his story with misguided attempts at levity.

I found Perry’s insecurity and use of humor as a crutch painfully relatable. I also have an addictive personality that has thankfully not taken me to the dark places where Perry hid in the depths of his sickness.

Otherwise, Perry’s life experiences deviate wildly from mine. His parents were young and unmarried when he was accidentally conceived.

That did not keep them from scoring formidable successes when Perry was still a boy. Perry’s mother was a legendary beauty and the press secretary for Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Perry went to school with Justin Trudeau, the son of the Canadian Prime Minister and a future Prime Minister himself.

The late actor’s father was an actor best known for his Old Spice commercials, while the Friends star’s stepfather was Dateline NBC host Keith Morrison.

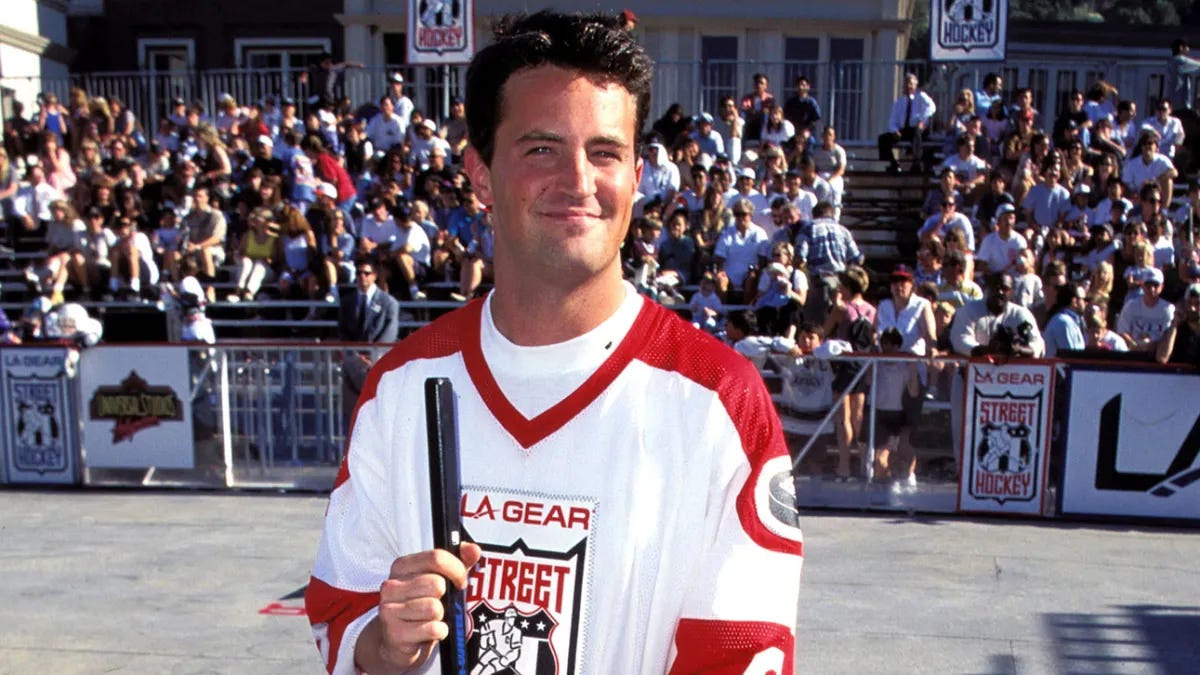

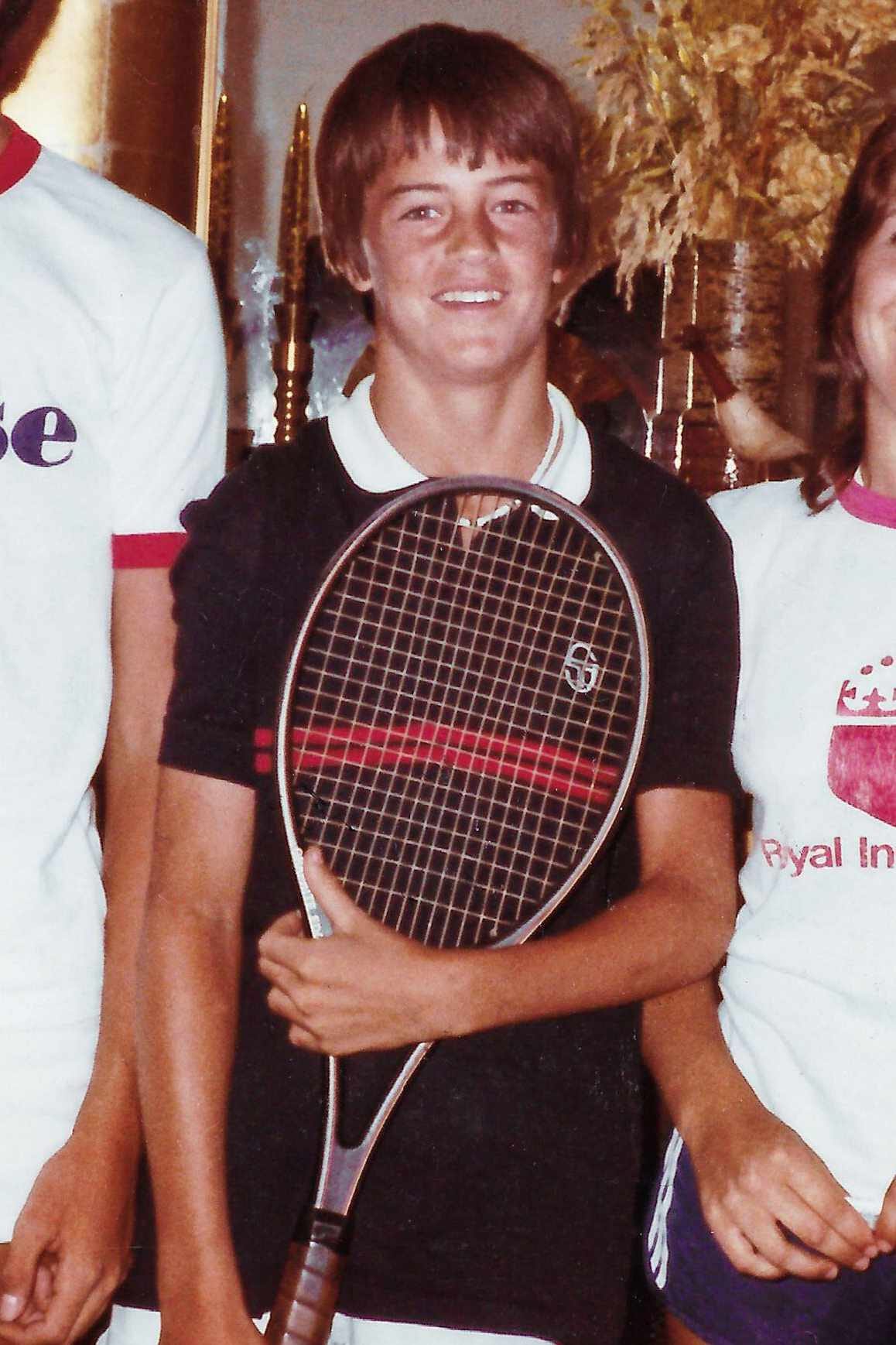

As if all that wasn’t impressive enough, the handsome, ambitious young man was a nationally ranked tennis player in his native Canada but struggled with American competition when he moved to Los Angeles as a teenager.

Despite being a Nepo Baby and child of privilege, Perry had a fear of failure and rejection that led him to reject the many beautiful women he slept with preemptively.

In an epic humblebrag, Perry writes extensively about wanting to settle down, get married, and raise a family but feeling a need to dump every woman he’s ever been involved with—including Julia Roberts—except for one, before they could dump him.

Perry returns again and again to what appears to be a formative trauma in his early life when he flew from his native Canada to Southern California by himself as an unaccompanied minor.

He sees this as a form of short-term abandonment and rejection that scarred him irrevocably. Like a lot of famous addicts, Perry nursed a terrible fear of being alone. He surrounded himself with people of both the kind and parasitic variety to alleviate his loneliness but also so that someone would be there if he overdosed.

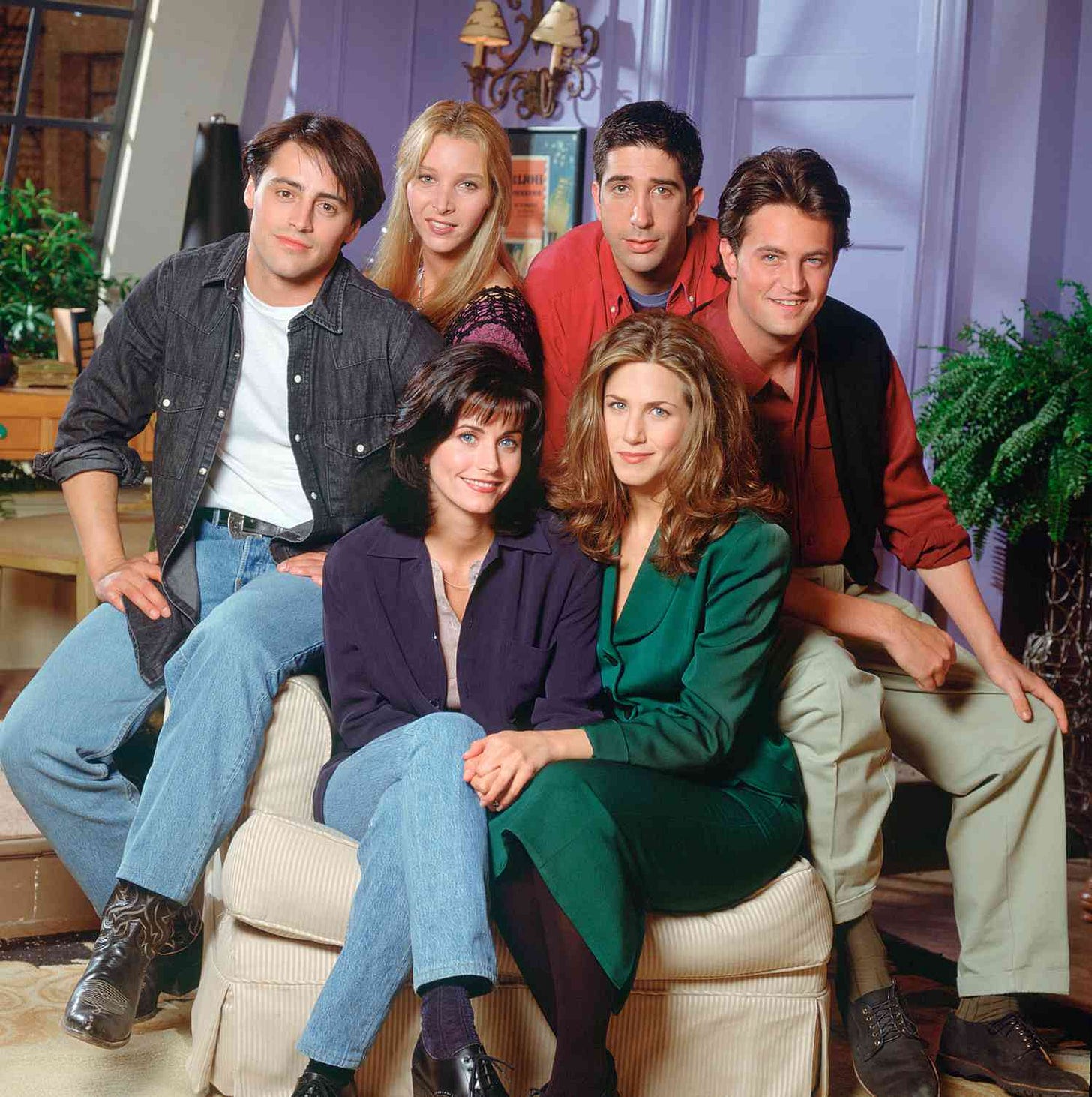

Perry is all too aware that the public is fascinated by him because he was a cast member of one of the most successful television shows of all time. In a blatant brag-brag, he calls Friends arguably the most beloved show of all time and the most beloved sitcom.

I don’t want to argue with the ghost of a man who recently died a particularly sad death, but Friends wasn’t even the most beloved sitcom that aired on NBC the same night as Friends. That distinction belongs to Seinfeld.

Friends was massive. No one could deny that. It was appointment television for a solid decade. Perry has a complicated relationship with the television show that made him a household name.

Incidentally, I wondered recently whether Friends would endure for future generations the way Cheers, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and other classic sitcoms have before I realized that the show has existed for three decades and is still absolutely massive, so it’s safe to say that it already has stood the test of time. Twenty years from now, it’ll undoubtedly still be wildly popular. There’s a reason Perry made twenty million dollars a year in Friends royalties every year.

Perry praises Friends as a creative, collaborative wonderland that welcomed input from anyone with a good idea or a clever gag, whether they were a star or a production assistant. He praises his costars, producers, and writers but doesn’t have much to say beyond that.

Though Perry does not mention it in the book, he was so drunk and stoned that there are three seasons he did not remember at all.

Perry was good friends with Hank Azaria and Craig Bierko when he was starting as a TV actor in LA. He mentions in passing that while Azaria certainly experienced success, in that he MADE HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS OF DOLLARS AS A CAST MEMBER OF ONE OF THE MOST SUCCESSFUL TV SHOWS OF ALL TIME, he didn’t have the Al Pacino career that he wanted.

That seems harsh, but Perry himself made tens of millions of dollars on one of the most popular shows in TV history yet clearly wishes he was known for his writing or dramatic acting and not for being a small-screen funnyman famous for his offbeat delivery (could he be more unique in that respect?) and physical comedy.

Perry’s memoir, which explores the dark, shadowy depths and darkness of a superficial man, is less concerned with his acting career or his eventful love life than in the Big, Terrible Thing that ruled, ruined, and ultimately took what only seemed like a charmed life from the outside.

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing is primarily a memoir of addiction from a man who took more pride in being able to help fellow alcoholics than in appearing in a show that paid him a million dollars an episode.

Perry’s memoir is forthright and engaging but also strangely and frustratingly glib. It’s a story of massive wealth and a cautionary yarn about being blessed and cursed to have the money and resources to do whatever you want, even if it ends up hurting and killing you.

At his worst, Perry took fifty-five Vicodin a day. He spent what should have been the best years of his life shuffling in and out of rehab. He spent close to ten million dollars getting sober, only to inevitably relapse when life threw something difficult his way.

Late in the book, for example, Perry’s front teeth all fall off. Perry was in a coma for months. Doctors gave him a two percent chance of survival. His colon burst, and he had to have a colostomy bag for close to a year.

Perry understood all too well the precarious nature of his sobriety. He knew that all it took was one bad day or night for his hard-won, hard-fought sobriety to disappear. He had everything someone like me could want but would trade it all not to be an alcoholic or an addict.

When I read Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, I wished it had been more raw and less jokey. I also would have liked more commentary on his television and film career. I wish it had been more like Will Harris's Random Roles and less a conventional tale of addiction.

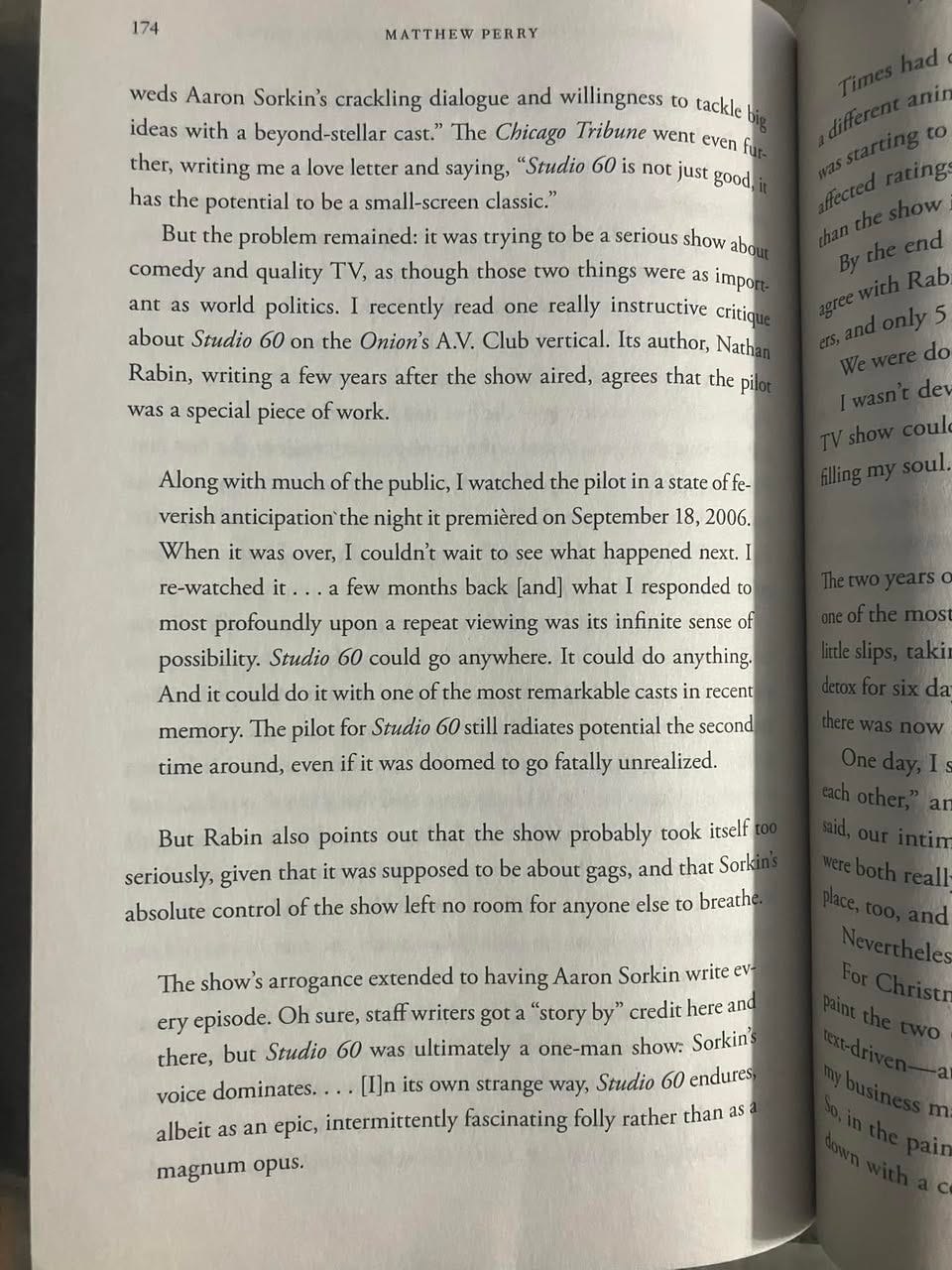

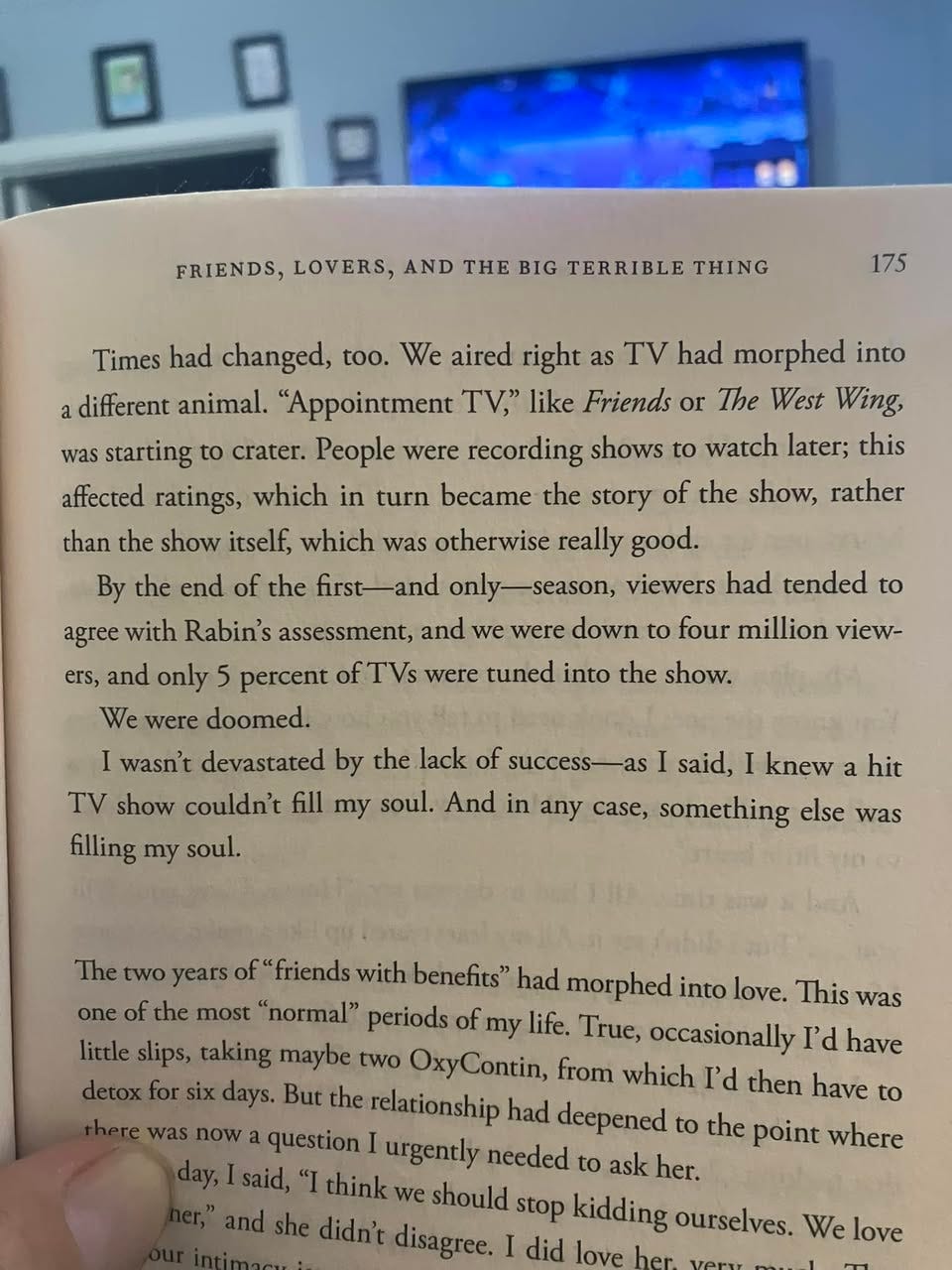

As someone morbidly fascinated by Studio 60 of the Sunset Strip, which gave Perry the curious distinction of being the star of one of TV’s biggest hits and one of its biggest flops, I would love to have read more about his experiences.

Unfortunately, the disconcertingly small section of the book devoted to Aaron Sorkin’s epic boondoggle is dominated by lengthy excerpts from a critic who panned it for treating something fundamentally silly—sketch comedy—as a matter of life-and-death importance.

In a deeply surreal development, the critic Perry references approvingly is me, Nathan Rabin, the kid from the group home with the world’s lowest credit score. He gave me the last word on Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, as well as the first and middle words.

I knew I was referenced in the book but did not realize that there's an entire page devoted to me and my My World of Flops piece on the failed drama.

Friends, Lovers and the Big Terrible Thing is neither a flop nor a secret success. It’s engaging in a superficial way but understandably weary of plunging too deep into the darkness of its author’s life and death.

Perry took writing seriously but worried about disappointing the public, who loved him as Chandler Bing, and worried about him as a profoundly flawed, troubled human being.

That’s one of the great things about memoirs: you find yourself relating on a deep emotional level to someone much different from you, with an antithetical set of life experiences.

Rest in Peace, Matthew Perry. I apologize for the dumb jokes I made at your expense and appreciate you telling your story, even if it’s not as moving or powerful as it might have been if you’d been more confident about the power of truth and testimony and less intent on sweetening your story for a mainstream audience he worried wouldn’t accept him unless he entertained them.

As a possible book for a future article, "Harpo Speaks!" may not be a lurid tell-all, but man you really get a feel for what Harpo Marx was really like, how he felt about performing with his family, how he was an honorary member of the Algonquin Round Table, and so on. Even if you can't relate to the era in which he lived (same here), it's really easy to picture as you read it. It's a comfort-food memoir, but one of the best I've ever read.

Good read, Nathan.

I think Matthew Perry's Keanu Reeves jokes in Friends, Lovers, and the Big, Terrible Thing were largely a reflection of how Reeves used to be regarded in the pop culture zeitgeist. Back in the early to mid '90s, he was largely regarded as a joke, a mediocre-at-best actor who got roles more for his good looks than his acting talent. That changed somewhere in the early 2000s, when he became the near-universally beloved celebrity he is today. I think Perry just missed that transition, and thought that Reeves was still widely regarded as the guy who couldn't do an English accent in Bram Stoker's Dracula.

And I had no idea that Sammy Davis Jr.'s Yes, I Can was a throwaway gag in The Simpsons. I thought it was a throwaway gag in This Is Spinal Tap.