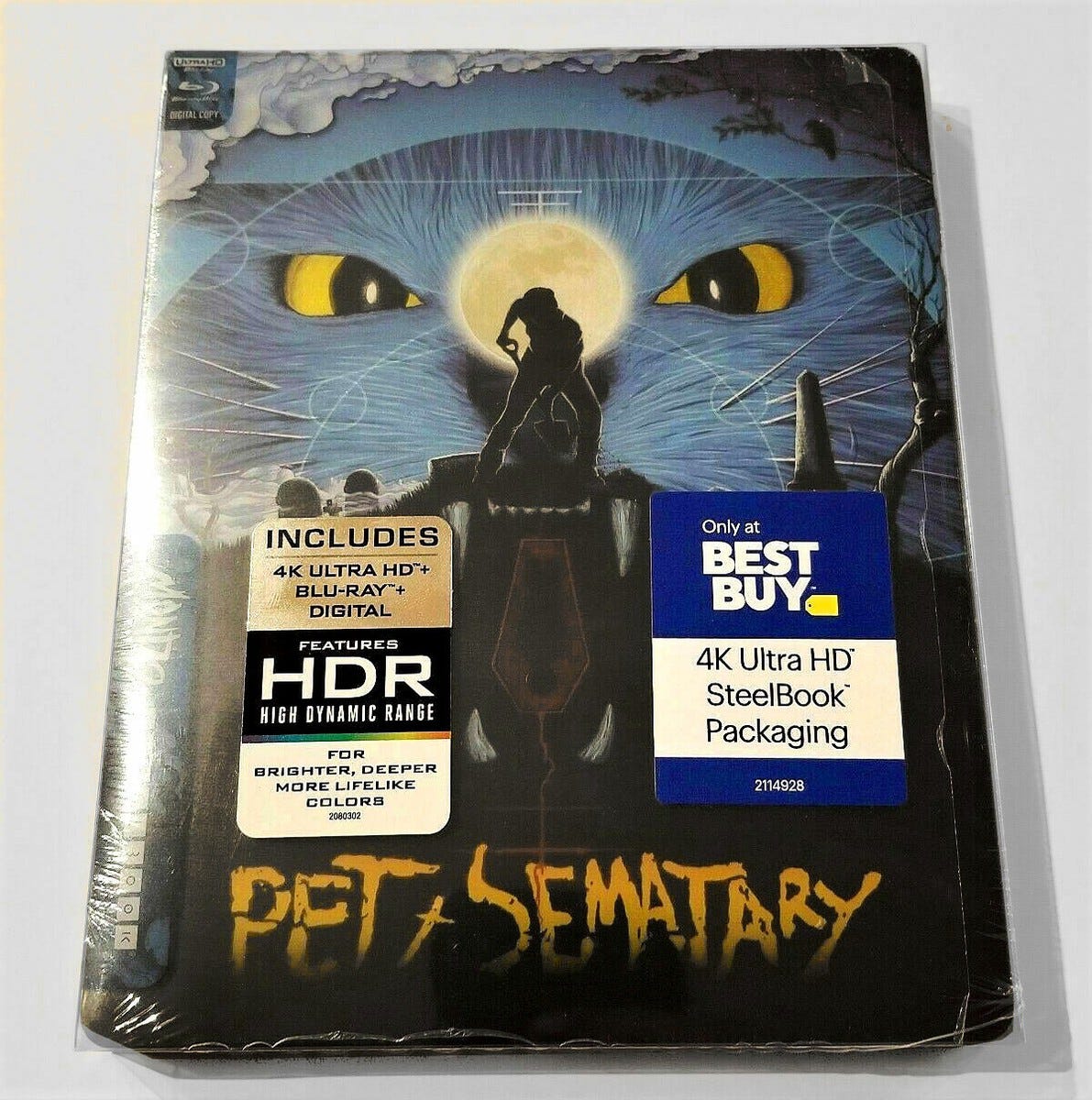

In the Classic 1989 Original Pet Sematary, Death is Almost Invariably Better

Please don't bury the Ramones in a pet cemetery. They don't want it.

In the entry on 2023’s Pet Sematary: Bloodlines, I wrote about how frightmaster Guillermo Del Toro singled out Pet Sematary as a terrifying masterpiece that he’d love to adapt.

The novel had special meaning for its author as well. Of everything he’s written, Pet Sematary scares him the most. He reportedly pissed himself with fear every time he sat down to work on it, but persisted all the same out of stubbornness and a cocaine-fueled fear that if he stopped his house would become sentient and eat him.

King has told countless interviewers that his greatest fear is being murdered by a pet or child who died, then was resurrected in a Native American burial ground with sour earth and unholy secrets.

The bestselling author insisted that Pet Sematary was nonfiction, that everything in it had happened to a friend of his, and that his skittish publisher had forced him to classify the novel as nonfiction because they were in the pocket of Big Native American Animal Sematary, which is surprisingly all-powerful.

King was so intent on using his art to dissuade readers from engaging in necromancy to raise the dead that he adapted the novel for film himself and contributed a Hitchcock-like cameo as a priest who presides over a funeral.

As with many of King’s novels, Pet Sematary was inspired by the writer’s life. While working as an artist in residence at the University of Maine, he lived near a highway where an unusually high number of animals met grisly ends at the hands of distracted long-haul truckers.

King’s daughter was one of many unlucky children. She lost a cat to the highway of doom. This allowed her dad to do what he does best: make money off pain, suffering, and death. He imagined what might happen if his cat returned three days later, changed.

Then King remembered the plot of “The Monkey’s Paw”, one of the most used and abused premises in all of pop culture, and had the premise for his latest bestseller.

The perfectly adequate Dale Midkiff stars as Dr. Louis Creed, a doctor who relocates from Chicago to the small town of Ludlow, Maine.

Ludlow has a certain pastoral charm, but it also has many disadvantages. The ground of the Native American burial ground is sour. It’s evil. It’s animistic. It possesses the unholy power of resurrection, a power that should be reserved exclusively for God or mad scientists.

Louis doesn’t know that when he moves to Ludlow. His real estate agent probably refrained from revealing its dark secrets out of an understandable fear of scaring homebuyers away.

That highway is a goddamn accident waiting to happen. Life hack: if so many critters are run over by 18-wheelers that they have to build a special burial ground to handle the sheer volume, move somewhere else.

This is triply true if you have a black cat named Church and a two-year-old son named Cage, as Louis does. Ludlow appears to be the roadkill capital of the universe. That highway to hell is killing the dogs. It’s killing the cats. It’s killing the pets.

As a doctor, death is an everyday concern for our bland yet passable protagonist. When he’s unable to save jogger Victor Pascow (Brad Greenquist), the prematurely deceased young man haunts him. He acts as the ghoulish angel on his shoulder, pointing him away from making a grief-fueled mistake he won’t live to regret.

On the other side of the doctor’s shoulder floats Jud Crandall (Fred Gwynne), a genial neighborhood man in overalls who warns his new neighbor about the dangers posed by death machines constantly zooming past his property.

When Church dies via truck while the doctor’s wife and children are away for Thanksgiving, Jud takes him to a spooky Native American burial ground and advises him to bury the feline corpse in it.

Church returns, but he is not the same. More specifically, he undergoes an unfortunate transformation from cute li’l cat with a fuzzy little belly you just want to pet to a kill-crazy monster from beyond the grave. He stinks. His eyes glow with ominous intent.

Jud concedes that things hadn’t turned out better when he tried to resurrect his pet dog many decades earlier. That’s one of several million solid reasons not to mess with the pet semetary’s ancient evil, but we would not have a movie if people did not behave in the stupidest possible way, with the most predictable of outcomes.

Like a real dumbass, Jud hypothesizes that maybe the problem lie in the species buried. He had a very negative experience with his furry little pal turning into a hellhound, but maybe unholy resurrection is different for cats. Maybe last time was a fluke, and this time the dead animal brought back to life through black magic will behave exactly like it did before, and not like every resurrected animal or human in the history of literature and film.

The studio was apparently reluctant to cast Gwynne in the key role of the nice older farmer who hands Dr. Creed the keys to his own damnation because they were worried that he was so typecast that audiences would look at him and see Herman Munster out of makeup.

Director Mary Lambert, a music video veteran and the original director of Prince’s Under the Cherry Moon, persisted, and the TV veteran scored the film’s juiciest role and a nifty little comeback.

Gwynne lends gravitas to the plum part of a world-weary survivor who knows the deadly dangers of knowingly transgressing the lines separating life and death, yet cannot keep himself from “helping” his friend in the least helpful possible way.

Jud knows he’s making a terrible mistake in hipping him to the Pet Sematary’s sinister mojo. When Dr. Creed’s two year old gets run the fuck over by a truck, the leading cause of death in Ludlow by a great margin, he knows that the mad-with-grief doctor will once again play God and tempt fate by burying something meant to stay dead.

It’s Gwynne who delivers the franchise’s most famous dialogue/wisdom: “Sometimes, dead is better.”

John Lithgow was a fine choice for the Jud role in the remake, but he does not utter Jud’s catchphrase with anywhere near the full-throated conviction Gwynne brings to the line.

Jud does terrible things for noble reasons. He wants to help alleviate his friend’s pain and all-consuming grief, but he does so in a manner that unleashes hell.

Dr. Creed similarly knows that he should not use the pet cemetery to bring back his son. But he does not behave rationally. He is not rational. He’s in so much pain that he will do anything to alleviate it, even if that means that his son will return not as he knows him but rather as a kill-crazy maniac out to prove that when it comes to slaughtering families, age and size are nothing but numbers.

Lambert shoots around zombie Gage because it’s hard to make something the size of a Teddy Ruxpin doll terrifying. The murderous undead Gage taunts his victims in a high voice filled with murderous intent. It’s all spectacularly silly stuff that takes away ever so slightly from the heaviness of the grief and mourning.

Pet Sematary didn’t do anything particularly new. It is, after all, a variation on “The Monkey’s Paw”, one of the most famous, influential, and adapted short stories in all of literature.

The novel became a sizable hit film because it spoke to something raw and real, and painful in the sense of loss, confusion, and yearning that comes with losing someone you can’t imagine living without.

Pet Sematary did not need to become a franchise, but there was something sticky and enduring about its premise that proved unexpectedly resonant.

The film’s moral might be simple, but it’s also true. When it comes to resurrections, the dead is almost ALMOST better, but that doesn’t keep fools from messing with the forces of death all the same.

Oof. This was a bit of a tough one to go through after having to have our cat put down yesterday, but after reading "he undergoes an unfortunate transformation from cute li’l cat with a fuzzy little belly you just want to pet to a kill-crazy monster from beyond the grave." - I suspect you, Rabin, have never owned a cat. This transformation is what we cat owners call "a normal Tuesday."

'Non-fiction',eh?I am perfectly willing to suspend disbelief, especially for a film that trucks in questionable behavior like trying to resurrect one's child based on the advice of a neighbor that could quite possibly have dementia,but King was clearly pulling(or trying to)the wool over our eyes with that(tongue in cheek?) statement.He later said that he barely remembered writing parts of the book,thanks to being in the throes of his alcoholism,which explained quite a bit,including why his protagonists so often sounded like 12 year old boys.Writers-gotta love 'em.