Death of a Unicorn is the Last Unicorn/Color Out of Space Mash-Up We Never Knew We Didn't Need

These ain't your daddy's unicorns!

In April, I will have spent a decade as a full-time freelancer, having been relieved of my staff position at The Dissolve shortly before it ceased existence.

I miss many things about my old life as a salaried staff writer for The A.V. Club and then The Dissolve. I miss going to Sundance every year. That was an enormous amount of work, as it was not unusual for a night’s work to wrap up at two or three or four in the morning, but it was also tremendous fun.

I have many fond, if fuzzy, memories from my time at the country’s most important film festival.

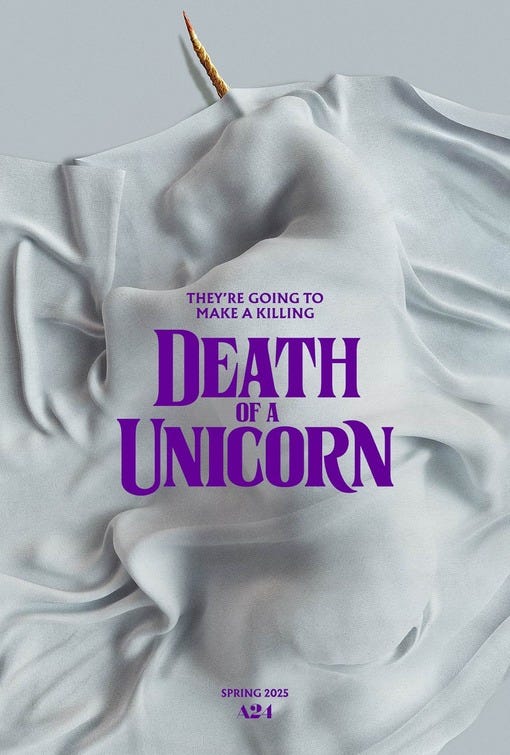

There are movies that I will always associate with Sundance, whether they played at the festival or not. I’m talking about movies like the morbid quirk-fest Death of a Unicorn, the Last Unicorn/Color Out of Space mash-up we never knew we didn’t need.

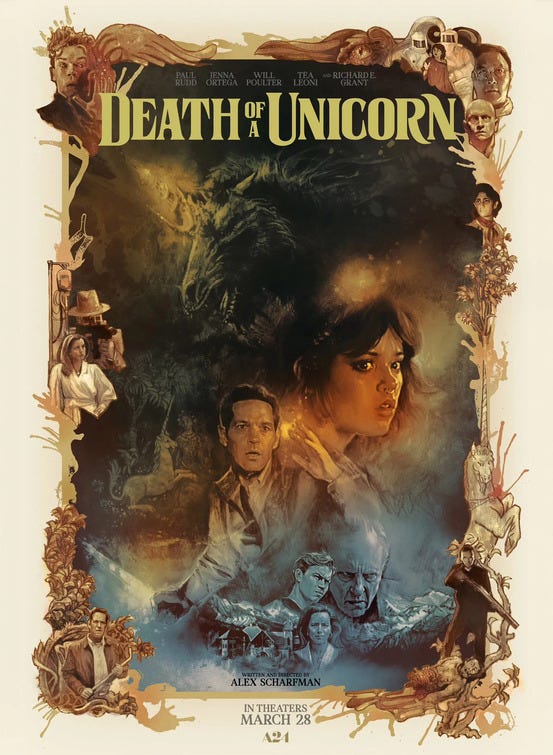

I can easily imagine flipping through the fat Sundance catalog, filled with dreams never to be realized, and stumbling upon Death of a Unicorn. It’s the kind of movie I’d see, primarily because of a cast that includes Paul Rudd, Jenna Ortega, Richard E. Grant, Will Poulter, and Tea Leoni, but also because of its dark and unusual title and premise.

These are not Lisa Frank unicorns but rather bloodthirsty beasts who think nothing of crushing a human skull with their massive hooves.

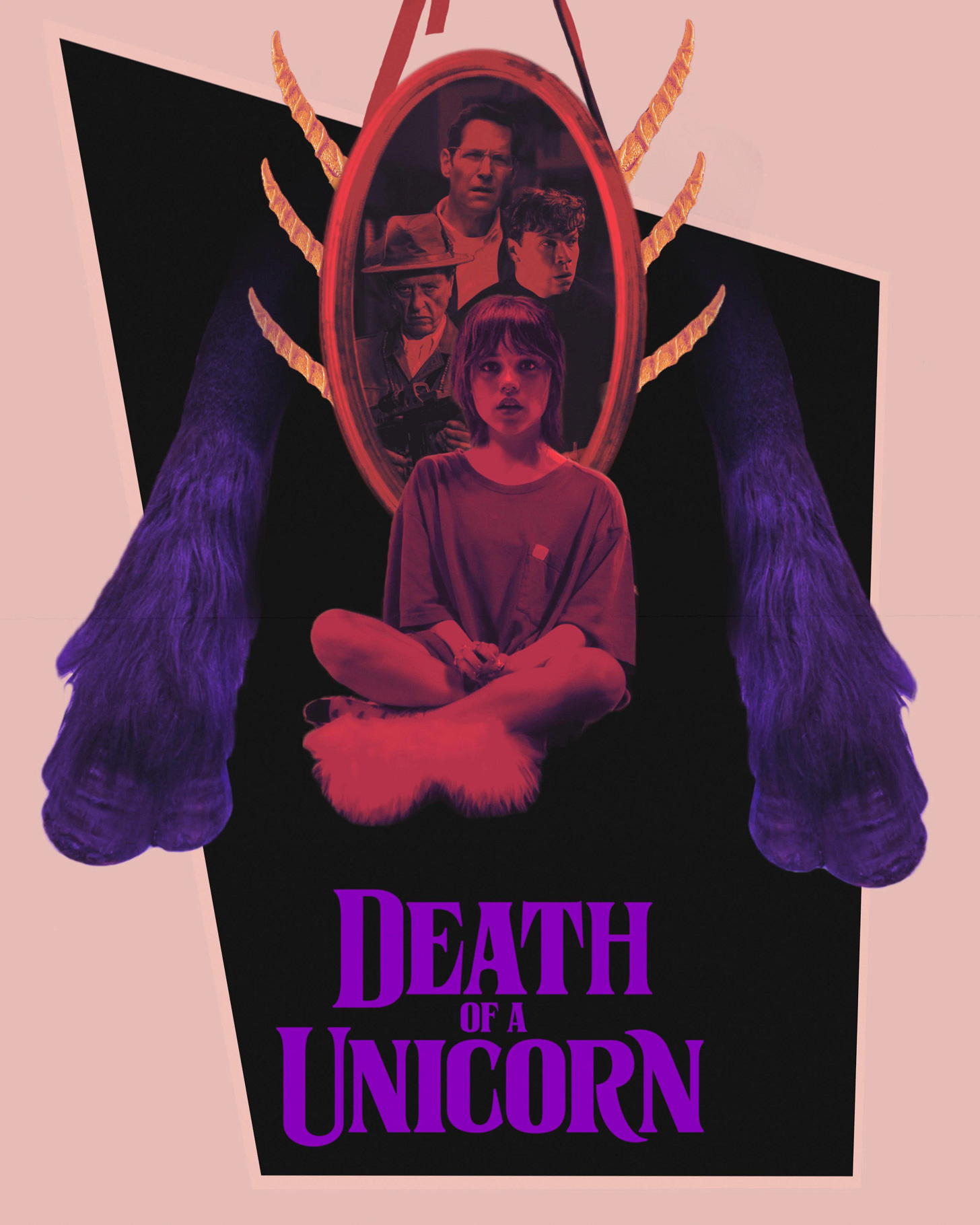

Ah, but I am getting ahead of myself. Death of A Unicorn begins by introducing protagonists Elliott (Rudd) and Ridley Kintner (Ortega).

Like the title character in A Working Man, which I just got back from, Elliott is a single father of a daughter and a widower. Otherwise, the films are quite different. If Death of a Unicorn is the kind of morbidly daffy fare that plays film festivals, A Working Man is more like a 1980s Cannon exploitation movie Menahem Golan would pimp at the frenzied buyers market that is Cannes.

Elliott is anything but a natural father. He has a hard time connecting with his college student daughter because he doesn’t know how to talk about their mother’s death in a sensitive, tactful way, but also because he’s just awkward.

Rudd is such an innately likable, charming, and sympathetic actor that it takes considerable effort for him to play someone who is not lovable or appealing. Death of a Unicorn casts perhaps our most lovable actor as someone largely devoid of charm or affability.

Elliott has prioritized his career and ambitions over his family and daughter. He’s a charmless schlub, a bloodless bureaucrat whose raw ambition has helped him climb the corporate ladder.

The semi-estranged father-daughter duo is headed to the palatial estate of Elliott’s boss, Odell Leopold (Richard E. Grant), a Mr. Burns type so sickly and feeble that it seems he has hours rather than days, months, or years to live.

En route to Leopold’s lavish home, Elliott hits a unicorn. Ridley touches its horn and has a transformative spiritual experience. Connecting with the unicorn on a soul-deep level engenders something approximating a transcendent psychedelic experience. It’s an incredible high from the unlikeliest source.

Ridley’s mind is blown twice. First, it’s blown by the appearance of a seemingly mythical creature bleeding to death in front of her. Then it’s blown by the incredible rush she experienced mind-melding with a beast whose powers appear unlimited.

Unfortunately for Ridley, while she’s still reeling from the trauma of her father accidentally killing an animal that ostensibly doesn’t exist, her old man is beating the unicorn to death with a tire iron.

Needless to say, not even Paul Rudd can beat an animal to death with a blunt instrument and remain likable. That’s a sure-fire way to get audiences to root against you, even if he sees the act, not without cause, as a mercy killing.

The accident leaves the dad-and-daughter duo in a pickle, particularly after his hosts notice the damage to Elliott’s automobile.

Odell’s family is as odious as he is, if not more so. He’s joined by scheming, utterly amoral wife Belinda (Leoni) and Shepard (Will Poulter), a failson in the Donald Trump Jr. mold.

They see, in the unicorn’s horn, blood and body, something not only otherworldly and unprecedented but miraculous.

Odell makes an incredible recovery. He goes from knocking hard on death’s door to feeling vigorous and dynamic. His cancer instantly goes into remission. He sheds years, even decades, in a matter of mere minutes.

The unicorn’s powers are amorphous and unlimited. The evil family at the center of the film is so powerful and connected that they have their own scientists and laboratories to analyze the unicorn’s magical properties.

Ridley looks at the unicorn corpse, filled with guilt, shame, confusion, and fear. She’s the only halfway likable or moral character in the film.

Everyone else looks at the uni-corpse and sees dollar signs, preternatural abilities, and raw power. They’re eager to use the unicorn’s gifts to improve their own lives, but equally excited about monetizing the dead unicorn as aggressively as possible by selling its blood and ground-up horn to other impossibly wealthy masters of the universe.

In its first two acts, Death of a Unicorn is a dark satirical comedy of greed and exploitation. Its characters are confronted with something mythical, magical, and God-like, and all they can think about is money and power and exploiting the dead unicorn until there’s nothing left.

The unicorns in Death of a Unicorn are beauties, if you’re generous, but they’re also beasts.

These are not the unicorns you’d find in sticker form on a Lisa Frank notebook. They are fucking huge. They have sharp teeth. They are not to be fucked with.

The mommy and daddy unicorns are established as formidable threats with incredible regenerative powers earlier in the film, but Death of a Unicorn doesn’t become a full-on horror movie until its third act.

Needless to say, the parents of the only temporarily dead unicorn are less than pleased that some of the most loathsome film characters in recent memory killed their child, then did all sorts of creepy, mercenary things to its body.

Death of a Unicorn is so relentlessly misanthropic and dark that it’s prohibitively difficult to care about them. Except Ridley, Death of a Unicorn is populated by degenerates who deserve to be killed in a gruesome fashion by mythical, magical creatures with bloodlust and body counts.

This horror comedy transforms the quirky horn that separates magical unicorns from boring, shitty-ass horses that everyone hates into a brutal weapon, as ferocious in its way as Jason’s machete or Freddy’s knife-gloves.

The unicorn parents are so vicious and massive that the humans don’t seem to have much of a chance. The magical motherfuckers seem to be on a higher evolutionary plane than us hapless humans, whom they, like the film, hold in low regard.

At Sundance you see so many movies in such a short time that they tend to blur together into one amorphous blob of daring, unusual but often underwhelming and forgettable fare.

That’s kind of how I feel about Death of a Unicorn. It’s been less than twenty-four hours since I saw it, and already my memory of it is beginning to fade.

So, while I found Death of a Unicorn engaging enough yet disposable and slight, it’s the kind of obscurity you end up catching on Netflix, where the cost is much lower, as are the expectations and stakes.

Three out of five