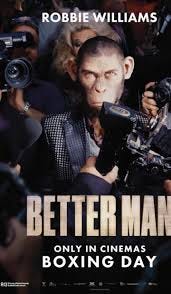

Better Man is a Crowd-Pleasing Musical That Will Have You Saying, "That Chimpanzee REALLY Loves Cocaine!"

He really does, though! It's like he's addicted or something!

When I learned that Michael Gracey, the director of The Greatest Showman, had made a biopic of British pop star Robbie Williams in which the musician is played not by a human actor but rather a computer-generated chimpanzee, I had the same reaction as everyone else. I wondered why ostensibly sane filmmakers would do something so bonkers and unique.

The answer, I suppose, is that the filmmakers chose to make a movie about the bad boy breakout star of Take That in which the protagonist is represented onscreen by a computer-generated image of a chimpanzee because it’s bonkers and unique.

There are many flashy big-screen biographies of self-destructive pop stars. None, understandably, have used a computer representation of a soulful primate with a bottomless hunger for booger sugar as its lead character.

That makes Better Man unique and original, two qualities the market hates. It’s not unlike how the aptly named Joker: Folie a Deux set itself apart from every other superhero sequel by being a musical, courtroom drama, and prison movie.

Joker: Folie a Deux was bonkers and unique but not good. Its central conceit was audacious but ineffective. That is thankfully not true of Better Man.

That makes Better Man a whole new kind of monkey movie. This isn’t C.I.Ape or Funky Monkey.

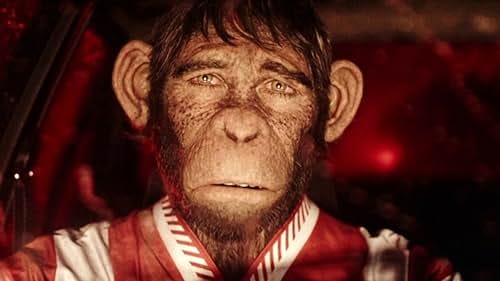

This is, instead, a movie about a chimpanzee that fucks. It’s about a chimpanzee who parties. It’s about a real party animal. Also, this chimpanzee loves to do cocaine.

But before a plethora of scenes that will make you sit up and think, “Damn, that monkey LOVES cocaine,” we’re introduced to li’l Robbie Williams as a working-class scrapper with a loving and supportive mother and grandmother and Peter (Steve Pemberton), his poignantly pathetic father. Peter Williams, who performed under the stage name Peter Conway, hungered for the limelight but possessed a talent level that ensured he would remain a small timer.

Robbie’s fierce desire to succeed is rooted in parental trauma. His dad was a small-timer who failed in his bid to make it as a singer. His son’s self-esteem was consequently wrapped up in being big-time and a success.

Our simian hero gets his love of performing from his father, as well as his reverence for the Rat Pack, specifically Frank Sinatra. He learns at an earlier age that he can get attention, good and bad, by acting out and making a nuisance of himself, which helped him professionally yet hurt him personally because no amount of attention, money, or success could fill the hole at the center of his being.

Robbie gets his first taste of fame when he auditions successfully for Take That, a British boy band put together by Nigel Martin-Smith (Damon Herriman) as a British answer to New Kids on the Block.

Like seemingly all boy band Svengalis, there’s something deeply off about Nigel. He goes out of his way to make Williams feel small and inadequate, at least in Williams’ telling.

Williams portrays his former bandmates as a bunch of assholes who made his already difficult and stressful existence even more hectic with their casual cruelty.

Better Man highlights, to an almost perverse degree, the homoerotic nature of Take That’s early persona. Williams’ narrator happily announces that many of the band’s first shows were for gay audiences more concerned with how the teenagers looked in skimpy outfits than with their sound or their songs.

Robbie butts heads with Gary Barlow (Jake Simmance), Take That’s frontman and primary creative force. Barlow sings lead, plays piano, and writes many of Take That’s songs.

Barlow is the antithesis of his bad-boy bandmate. He’s been married for nearly a quarter century and has four children. He’s the responsible face of Take That, while Williams is the wild card, a charismatic and ambitious performer and the bane of his bandmates’ existence.

The first act of Better Man is nearly as homoerotic as Can’t Stop the Music, the infamous Village People musical. Williams isn’t hiding or downplaying the gay origins of the band that brought him fame and fortune; he’s playing them up.

Better Man’s first act is gloriously gay and heartwarmingly homoerotic. Its subsequent two acts are dominated by cocaine.

Fame does not make Williams happy. It does not free him from feelings of inadequacy and anxiety. It has the opposite effect. It makes him miserable. Better Man is refreshingly candid in its depiction of its protagonist’s fierce battles with mental illness, in the form of clinical depression and ADHD as well as his battles with alcoholism and drug abuse.

Massive stardom gives Williams the money and power to be the worst, most selfish, and most destructive version of himself.

Williams rocketed to massive worldwide fame but could never escape himself or his demons, represented here by angry simian versions of the younger Williams glaring at him during concerts.

Gracey does not avoid the cliches of traditional biopics. Better Man hits so many of the expected beats that, at times, it feels like a non-comic, non-ironic version of classic rock biopic spoofs Walk Hard and Weird: The Al Yankovic Story.

The filmmakers indulge every rock and roll movie convention, confident that they’ll be able to sell this achingly familiar material with energy, passion, and an ultimately liberating sense of vulgarity.

Gracey is a true maximalist. Everything in Better Man is turned up to eleven. It’s an endless series of climaxes that should be exhausting but is instead wildly entertaining.

Better Man solidifies its director’s status as an auteur and shameless performer. It’s so similar to The Greatest Showman that it might as well be called The Second Greatest Showman.

Making Williams's younger self a computer-animated monkey proves a master stroke. Stardom separates stars from the rest of humanity. It makes them different from other people. That difference can be a source of great joy and utter despair. It’s not just that their lives are different; they practically belong to a different species, one more magical or rare than the one we happen to belong to.

The movie’s monkey business pays off with a protagonist who is more human than the human protagonists of 95 percent of conventional dramas. The computer animation has an expressiveness and emotion and there is a grace and pathos to the motion capture acting.

I saw Better Man at a ten o’clock showing on Sunday night in an empty theater. I was tired after a very long week. Better Man does not need to be two hours and fifteen minutes long, but it was like a shot of adrenaline into my eyeballs. Besides, everything about this is deliberately, purposefully excessive. Why should its runtime be any different?

Better Man was a critical hit but a commercial flop. That’s backward, considering Williams is all about entertaining the masses and collecting the rewards of super-stardom. Williams and Better Man are shameless populists aiming squarely at the widest possible audience.

I worry that the film’s commercial failure will have a chilling effect on oddball biopics. This means we’ll probably never see a movie about Taylor Swift where she’s represented onscreen by a puppet horse or a Drake biopic focussing on a stop-motion-animated yeti.

That’s a shame, but it also makes this even more of a kooky and irresistible outlier. Better Man has exactly the right amount of monkey business for me to get involved with.

Four Stars out of Five

TBH, I don’t know how much of Better Man’s flopping is just “Americans don’t know who Robbie Williams is.” So the conceit probably strikes American audiences as a “mere” gimmick (even though the actual reviews are very good).

Every comment section inevitably devolves into British people trying to convince Americans that Robbie Williams is really massive, actually.